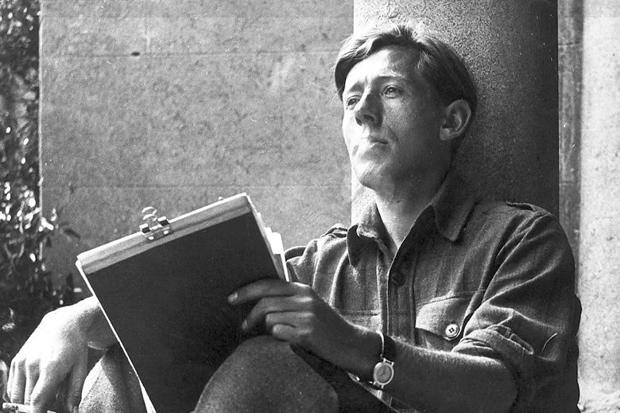

Writer Laurie Lee

Some places capture your heart because they are yours, and others, because they belong to someone whose words weave a spell that draws you in.

My husband and I were on an autumn vacation in the Cotwolds and on our way to Sheepscombe, a picturesque village in Gloucestershire, when I realized how close we were to Slad, the childhood home and final resting place of English writer Laurie Lee. Of course, I insisted on a little detour.

Those who’ve taken memoir workshops with me may recognize Lee’s name from a quote I’ve shared. I discovered it online more than a decade ago — before I’d read much about Lee — and it was so lyrical that I thought it part of a poem. (No surprise, since Lee is also a poet.) In fact, it’s from the essay “Writing Autobiography,” which appears in the collection I Can’t Stay Long.

“A day unremembered is like a soul unborn, worse than if it had never been. What indeed was that summer if it is not recalled? That journey? That act of love? To whom did it happen if it has left you with nothing? Certainly not to you. So any bits of warm life preserved by the pen are trophies snatched from the dark, are branches of leaves fished out of the flood, are tiny arrests of mortality. . . .”

Amid the Cotswolds’ lush rolling fields, hills, and valleys, its homes of gilded limestone that glow in the sunlight and occasional thatch-roofed cottages, it’s difficult to choose a favourite place, but the serene charm of Slad is hard to resist. We strolled through a village seemingly untouched by time. That’s an illusion, of course — there’s now a major roadway not far away — but to the visitor’s eye, Lee’s birthplace seems not unlike what he might have known and written about so fondly.

Lee, one of England’s most fabled writers — poet, novelist, travel writer, memoirist — was born in 1914 in Stroud. His father left the family when Lee was three years old, and his mother moved with her eight children to the Slad, a twenty-five-cottage village less than three miles away. Lee’s childhood home there, one of three in rundown Bank Cottages (now restored and known as Rosebank), was central to Cider with Rosie, the first book in his memoir trilogy.

Lee, one of England’s most fabled writers — poet, novelist, travel writer, memoirist — was born in 1914 in Stroud. His father left the family when Lee was three years old, and his mother moved with her eight children to the Slad, a twenty-five-cottage village less than three miles away. Lee’s childhood home there, one of three in rundown Bank Cottages (now restored and known as Rosebank), was central to Cider with Rosie, the first book in his memoir trilogy.

“It was never a show village,” Lee once explained. “It was a typical village cut off from the world. I still dream about the valley — the church bell from which you knew the time, sounds of farm dogs and running water, the quality of light on fields. I smell the rotting vegetation, the roasting grass of summer, dust.”

In “Writing Autobiography,” he describes the process of bringing the village to life in his memory and on the page:

“The village was small, set in a half mile of valley, but the details of its life seemed enormous. The problem of compression was like dressing one tree with leaves chosen from all over the forest. As I sat down to write, in a small room in London, opening my mind to that time-distant place, I saw at first a great landscape darkly fogged by the years and thickly matted by rumour and legend. It was only gradually that memory began to stir, setting of flash-points like summer lightning, which illuminated for a moment some field or landmark, some ancient totem or neighbour’s face.

“Seizing these flares and flashes became a way of writing, episodic and momentarily revealing, to be used as small beacons to mark the peaks of the story and to accentuate the darkness of what was left out. . . .”

Holy Trinity Church sits high atop a hill overlooking the short main street, which is so quiet there aren’t even streetlights. As you follow the path past the unkempt graveyard to the church’s front doors, to the left you’ll see Lee’s conspicuously well-kept gravestone.

From there you can look down to the town’s local watering-hole, the Woolpack Inn, named for the cloth mills that once speckled the valley. Lee’s once favourite hangout is now frequented by hikers as well as locals. The day we were there, several vehicles clogged the narrow main road, and laughter floated up from streetside patio. Nearby is Rose Cottage, Lee’s home from 1961, which he described as “six stumbling paces from the pub, door to door,” and across the street, the one-storey schoolhouse that Lee had attended.

From there you can look down to the town’s local watering-hole, the Woolpack Inn, named for the cloth mills that once speckled the valley. Lee’s once favourite hangout is now frequented by hikers as well as locals. The day we were there, several vehicles clogged the narrow main road, and laughter floated up from streetside patio. Nearby is Rose Cottage, Lee’s home from 1961, which he described as “six stumbling paces from the pub, door to door,” and across the street, the one-storey schoolhouse that Lee had attended.

Breathtaking valley views form the village’s backdrop. It’s not at all hard to see why Lee was enamoured.

Yet he had a young man’s wanderlust. At age nineteen, he set off on foot seeking adventures, about which he would write in two later memoirs, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning and A Moment of War. In the former, he writes:

“It was 1934. I was nineteen years old, still soft on the edges, but with a confident belief in good fortune.

“I carried a small rolled-up tent, a violin in a blanket, a change of clothes, a tin of treacle biscuits, and some cheese. I was excited, vain-glorious, knowing I had far to go; but not, as yet, how far.”

Lee earned a little money along the way playing violin, and his explorations took him to London and other parts of England, and then to Spain, which was on the brink of civil war. He left when war broke out but returned as an International Brigade volunteer. An epileptic, he didn’t see any fighting and was soon shipped home, where he began to focus seriously on his writing and art.

For many years, Lee worked mostly as a journalist and as a scriptwriter. It wasn’t until 1959, at age forty-five, that he saw the publication of Cider with Rosie. Going on to sell more than six million copies, his childhood memoir has never been out of print.

The book’s success allowed him to turn to writing full-time, and to purchase Rose Cottage — where he lived with his wife, Catherine Podge, whom he’d married in 1950, and their daughter, Jessy, born in 1963.

In Cider, Lee conveys his childhood love of nature among the woodlands and combes [steep, narrow valleys]. He captures, as well, the dusty roads and poverty, the hardships and violence. “The autobiographer’s self,” he reflects, “can be a transmitter of life that is larger than his own — though it is best that he should be shown taking part in that life and involved in its dirt and splendours.”

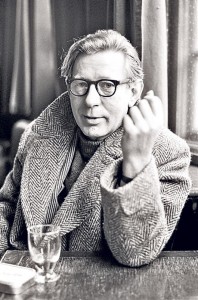

Lee himself had a darker side. In a 2013 interview, his daughter Jessy revealed that as well as suffering from epilepsy, he exhibited extreme mood swings, exacerbated by the fact he “liked a drink or two.” Lee’s biographer, Valerie Grove (Laurie Lee: The Well-Loved Stranger), writes of his affairs and frustrated literary ambitions and describes Lee’s last years as “forlorn.”

Lee himself had a darker side. In a 2013 interview, his daughter Jessy revealed that as well as suffering from epilepsy, he exhibited extreme mood swings, exacerbated by the fact he “liked a drink or two.” Lee’s biographer, Valerie Grove (Laurie Lee: The Well-Loved Stranger), writes of his affairs and frustrated literary ambitions and describes Lee’s last years as “forlorn.”

Journalist Robert McCrum of The Observer wrote, “When Cider With Rosie was eventually published, to astounding success in 1960, it was an autobiography notable for the fact that it stopped when its hero was 23, the year he left his native Gloucestershire. Laurie Lee was then 45. He would write nothing to match it ever again. In his prime he was known as a poet who had written a book, but in the end he would be known simply as a prose writer who had formerly written poems.”

Yet these revelations do not diminish the magic of his writing or his legacy.

And there’s an epilogue.

Eighteen years after her father’s death, Jessy Lee discovered among his papers in the British Library eight unpublished essays, which she described as “a great gift from the grave.” These were subsequently included among thirty-two in a new collection titled Village Christmas: And Other Notes on the English Year, published last year by Penguin Classics.

“The quality of the essays is impeccable,” Norah Perkins, Lee’s literary agent at Curtis Brown, told The Observer. “They are in turn profound, funny, wistful, fierce, thoughtful, and always beautifully written, beautifully observed. The essays in Village Christmas confirm Laurie’s ability to show what is sublime within what is humble.”

In one essay, he reminisces about a harvest festival some twenty years earlier, concluding,

“That was how it was. It is not so any more. But the ghosts of those old hymns sing through us still, though the bill of our gratitude must now be expressed in things other than wheaten sheaves. Meanwhile, the grassy combes and wooded crests of the Stroud valleys do not change, nor their rioting flowers, placid silences, nor the purple distances seen from their hills. And in spite of all the power and richness of modern life, it is here I most wish to be, where the landscape offers its endless festivals to the eye and to the spirit, perpetual harvests.”

The Slad Valley, like Lee’s literary depiction of it, lingers in the visitor’s imagination. It remains a place of stone cottages, velvet-green vistas, tall grasses and wildflowers, and a monument to a writer whose work, all these years later, still fascinates us.

Laurie Lee died on May 13, 1997, at the age of 82. The epitaph on his gravestone reads, simply, He lies in the valley he loved.

This is a beautiful piece. I love his books (oh, Cider with Rosie! So gorgeous…) and treasure The Firstborn, an essay (published by the Hogarth Press in 1978), given to my husband and me as a gift when our first child was born. It’s inscribed to us by Laurie Lee…