“I believe that memoir isn’t an exact record of experience but instead an artful arrangement of truth that creates a specific experience for readers.”

~ Lee Martin

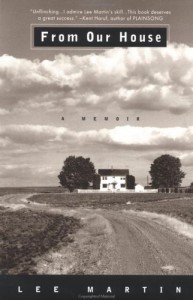

LEE MARTIN is the author of the novels The Bright Forever, a finalist for the 2006 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction; River of Heaven; Quakertown; and Break the Skin. He has also published three memoirs, From Our House, Turning Bones, and Such a Life. His first book was the short story collection The Least You Need to Know. He is the co-editor of Passing the Word: Writers on Their Mentors. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in such places as Harper’s, Ms., Creative Nonfiction, The Georgia Review, The Kenyon Review, Fourth Genre, River Teeth, The Southern Review, Prairie Schooner, and Glimmer Train. He is the winner of the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Ohio Arts Council. He teaches in the MFA Program at The Ohio State University, where he is a College of Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of English and a past winner of the Alumni Award for Distinguished Teaching. Visit his website.

LEE MARTIN is the author of the novels The Bright Forever, a finalist for the 2006 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction; River of Heaven; Quakertown; and Break the Skin. He has also published three memoirs, From Our House, Turning Bones, and Such a Life. His first book was the short story collection The Least You Need to Know. He is the co-editor of Passing the Word: Writers on Their Mentors. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in such places as Harper’s, Ms., Creative Nonfiction, The Georgia Review, The Kenyon Review, Fourth Genre, River Teeth, The Southern Review, Prairie Schooner, and Glimmer Train. He is the winner of the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Ohio Arts Council. He teaches in the MFA Program at The Ohio State University, where he is a College of Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of English and a past winner of the Alumni Award for Distinguished Teaching. Visit his website.

~~~

I welcomed Lee as guest author to the spring session of my online course Memories into Story: Life Writing (University of Toronto, SCS). What follows is an edited version of my students’ interview with him. Prior to the interview, they read the following short memoirs:

“All the Fathers That Night” (Such a Life)

“Heart Sounds” (River Teeth)

“Never Thirteen” (Such a Life)

Thank you, Lee, for such thoughtful and insightful responses to these questions about memoir writing and the writing life.

How long were you writing before you got published? And what were your challenges along the way?

I guess I’ve written all my life, but I never took a creative writing class until I was an undergraduate at Eastern Illinois University. That’s where I started to dream about one day entering an MFA program. I got my undergraduate degree in 1978 and stuck around another year to earn an MA. I worked for three years after that, and I kept writing and sending things out to journals with no luck. Then in 1982, I was accepted into the MFA program at the University of Arkansas. That marked the start of my serious study of the craft of writing. I didn’t publish anything until 1987. I needed all those years to read the things I needed to read, to keep practising my craft, and to live enough life to know its complications and its mysteries. In other words, I needed time to have something to shape and to know how to shape it.

My biggest challenge along the way was to keep going. I got very dejected and threatened to stop writing a number of times. I never did. I’m stubborn that way, and that’s a good quality for a writer to have. Thicken your skin and keep studying and practising your craft.

At what point did you develop confidence in your authorial voice?

I read a collection of short stories called Rock Springs by Richard Ford, and in them I heard a voice very similar to the voices of my native small-town Midwest. I’d been writing stories set in other places because I thought no one would be interested in those small towns. Ford’s voice unlocked something for me, and I wrote the stories in my collection The Least You Need to Know. It was the first time I felt that I’d successfully blended voice and material. It was the first time I’d felt the power of my natural voice, and it’s paid off for me in both my fiction and my nonfiction.

What is your daily process as a professional writer?

A typical day begins with a run. Physical exercise gets me focused. Then, after breakfast, I sit down to write. I usually pick up in the middle of something I’m drafting. I try to end one day’s writing session in the midst of a scene, so it will be easier to continue the next day. I used to write everything longhand, but I’ve given in to the computer these days, and I have to confess I sometimes use social media as a distraction. I’ve noticed, though, that sometimes the distraction allows my subconscious to work on a particular problem I’m facing in the writing and to come to a solution. Looking away from the writing, in other words, sometimes allows clearer thinking. Just don’t forget to come back from the distraction. I try to write for at least two hours a day during the school year and longer during the summer months. Little by little, each day, I push a piece of writing along.

Allyson taught us how to kick-start our memories by using several different methods, freewriting, observing/note-taking, clustering, sketching a map, creating a list, journalling, etc. Have you used any of these methods or others to help craft a story? Or do you simply sit down with an idea and begin writing?

I’m a big believer in freewriting, clustering, list-making, etc., as ways to bring material to the page or to deepen it once it’s there. That said, I don’t believe I used any of these techniques when I wrote the three pieces that you read. With those, I just found a place to start and then I opened myself to the powers of narrative and free-association. I never begin with ideas. In fact, I don’t believe in ideas in general in essays, which is to say, I trust the specific things from memory or from the world around me in the present time to become both conveyors and containers of the ideas that lift up from a particular essay.

Do you create outlines?

No, I never make an outline. Instead, I make myself curious and I write to satisfy that curiosity.

Which type of memoir do you find more effective: one in which the author tells the story as though reliving the past? Or, one in which the author reflects on the past from the age they are now? Or a combination of the two?

For me, the most effective memoirists move back and forth between the perspective of the younger self and that of the older one. The first dramatizes the experience; the second makes meaning from it.

In the memoirs we read, you tend to focus on a single topic, the kiss, the stroke, etc. I enjoyed this and the way you kept wandering from the topic and then coming back to it. Do you have any suggestions for crafting such an essay?

In the memoirs we read, you tend to focus on a single topic, the kiss, the stroke, etc. I enjoyed this and the way you kept wandering from the topic and then coming back to it. Do you have any suggestions for crafting such an essay?

I usually start with something very specific from memory or from the world around me at the present time, and then I see what else that specific thing might invite into the piece. If an essay works by letting us eavesdrop on the writer’s mind at work, we have to be open to what may seem like digressions. Those digressions, though, should ultimately lead us somewhere. I don’t like to know where I’m going or why I’m writing about these two things or these three things (or four, or five, etc.). I like the writing to show me. I see it as my job to figure out as the writing is underway what the connection is between the various elements of the essay. I usually know what that is when I’m nearing the end, and I write a line that contains them all, a line that resonates with me — surprises me, even. If I don’t get to that line, I at least get to an understanding of why the piece contains the elements that it does. Then I can revise the essay and usually find that final resonant line. You might start a piece with a particular memory and then ask yourself why that memory is important. You might also say to yourself, “When I remember ‘X,’ I also remember this, this, and this.” Let your mind associate. It will usually call up the elements that are demanding your attention. Your job is to write your way to connection.

“The barber works with wood” — the opening line of “All Those Fathers That Night” — is an effective hook for the reader. Did you start with this, then develop the story, or the other way around?

Yes, I started with that line and then just saw where it might lead me. I started with the memory of how my hometown barber was also a woodworker, and I wrote that first line. The other thing that stood out about him for me was the fact that he had all those daughters. So without knowing exactly where I was going, I was off on an examination of fathers and their children, but I got there by just paying attention to the details of the woodworking. The things of our worlds will often take us to the material we’re meant to write in a less direct, but more effective, way than if we tried to go at that material head-on. If I start by writing about a barber who works with wood, the stakes for me are much less intimidating than if I start by writing about my own complicated feelings about fatherhood. Using a small detail from the world around me, or from my memory, frees me to let language take me where I’m meant to go.

Your father, and your strained relationship, plays prominently in your stories. Such an important relationship — is it difficult to write about it?

I first wrote about my relationship with my father in the guise of fiction in my first book, a collection of stories called The Least You Need to Know. I waited until both of my parents were gone to write about the family in nonfiction. I was ready to face that material head-on, but, yes, it’s still sometimes uncomfortable. I tell my students, though, that when you find yourself at an uncomfortable place in what you’re writing, that’s a sign that you’re delving into the important stuff. We have to be brave at those points. We have to bear down. We have to make ourselves keep looking, keep living in that uncomfortable memory, etc. knowing that we’re safe because of time and distance, knowing that there’s a wiser, more confident version of the person we once were who is telling us it’s all right, stay in the moment, I’ll help you make meaning from it.

Do you struggle with an over-the-shoulder critic when writing about your parents?

There is no room in the writing space for any kind of over-the-shoulder critic. If you’re worried about what someone might think of what you say, you won’t say it, and something important will be lost forever. My only filter when I write nonfiction is my adult self. In other words, my experiences as a child pass through the perspective I offer as an adult.

Do you find it easier to express feelings through your child’s voice?

I’m not sure that my child’s voice ever leaves me. I hope it blends with my adult voice to make a more textured sound.

As you write about negative life events, do you gain release from those memories?

As you write about negative life events, do you gain release from those memories?

I wrote a blog post recently about how writing my first memoir, From Our House, allowed me to release a good deal of the anger that I’d carried with me too long as the result of growing up in a house with a violent father. So, yes, I do believe that we write about our lives to gain some measure of control of them. When we dramatize the moments from our lives, we can’t ignore them. We announce them to the world in some form or other, and, if we’re open to the art of empathy, we can gain a good deal of understanding about ourselves and others. We make art from our lives in order to understand them better.

How do you feel about manipulating time or location in memoir? Or about making up dialogue or collapsing two scenes into one? How much of this can one get away with before it crosses the line from memoir to fiction?

You’ll find two schools of thought on the manipulation of time, of course. Some will say that we have to be faithful to chronology; others believe we can telescope time. I fall into the latter camp. I sometimes move a scene around in chronology for the sake of the narrative arc. I do this because I believe that memoir isn’t an exact record of experience but instead an artful arrangement of truth that creates a specific experience for readers.

I’ve never changed the location of an event to make it more dramatic. Drama in memoir comes most often from what’s at war inside the memoirist as he or she puts the scene on the page and then steps back to reflect on it, so the setting of a particular event shouldn’t be the sole provider of tension, but the trigger for it. If we can’t make that happen by keeping the event in its factual location, we won’t be able to make it happen in a fictional setting.

Although I believe that we can modify dialogue and combine events into one, I also believe that we know when we’ve crossed the line from memoir to fiction, and that usually happens when we realize that we’ve altered things for a self-serving purpose, whether that be revenge or self-preservation, instead of for the purpose of truth-seeing.

What tips could you share for writing dialogue in memoir?

I’m not a memoirist who believes in staying faithful to exactly what someone said at a specific time. In other words, I craft my dialogue to make it more interesting. Does that mean I make things up? Not really. It means I know my people so well that I can grab onto the things they did say and also the way they might have said things they really didn’t. All of that said, though, I caution against having someone say something completely out of character for them. You can do that in fiction, but not in memoir.

In “Never Thirteen,” you switch between past and present tense very naturally. What advice could you offer on how to do this?

I establish the dominant tense (present) in the opening, and I stay true to it. Even though I’m writing about something from my past, my first kiss, I choose to write about it in the present tense to better capture what it felt like to be thirteen. I believe I pretty much stay in that tense until the end when the memory of the Peeping Tom enters and I have to render it in the past tense. Notice, though, that I’m always finding ways to blend that with what’s going on for me, the thirteen-year-old, in the present tense. If you read closely, you’ll also be able to pick out the adult perspective in that present tense: “I can never fully know the accommodations they had to make after my father lost his hands, but I can remember their murmurs behind closed doors — the sound as lulling as the cooing of mourning doves, as soothing as the rill of a brook hidden in a deep woods, a private code between them — and know that all the while I thought them impotent and numb they were making love each day right before my eyes, and I was too blind to see it; I was too busy being young.” We have to remember that tense is a way to make clear perspective and personae. There are many selves at work in a memoir, and the management of tense is often a way to allow those selves to engage in conversation.

“Never Thirteen” is filled with juxtapositions: the affection from Beth and the whippings from your father, the contrast between your father’s angry exterior and his actual vulnerability. Did you set out to identify contrasting ideas and work them into the story?

For some time, I’ve been challenging myself to see the opposites in any given situation. I do this as a way of investigating the complexities and contradictions of human behavior. So, yes, I was aware of the juxtapositions, particularly those of the sweetness of first love and the brutality in my father’s story, Richard Speck, the Peeping Tom, etc.

“Heart Sounds” and “All Those Fathers That Night” each have different but effective structures. How do you come up with a structure that you know will suit a particular piece?

I’m not sure, to tell you the truth. Maybe on some instinctual level I know that I have a story to tell, and I know that the story alone will let me explore something I need to explore. At other times, I sense that the place where I start won’t be enough to carry the essay, so I start to experiment with forms that will allow more into the piece. I never really think about form and content until I have a first draft. Then I know better what I’ve come to the page to say.

There’s a Part 2? Part 1 is filled with helpful insights.

Lee was a fabulous guest, Mary, eloquent and generous in his answers. I agree he’s shared many insights here. There is indeed a Part 2. 🙂

Wonderful interview…is it me, or is memoir the most thought-provoking of writing pursuits?

But, Allyson, I guess you knew that!!