HELEN HUMPHREYS is the author of four books of poetry, six novels, and two works of creative nonfiction. She was born in Kingston-on-Thames, England, and now lives in Kingston, Ontario.

HELEN HUMPHREYS is the author of four books of poetry, six novels, and two works of creative nonfiction. She was born in Kingston-on-Thames, England, and now lives in Kingston, Ontario.

Her first novel, Leaving Earth (1997), won the City of Toronto Book Award and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Her second novel, Afterimage (2000), won the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, was nominated for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize, and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Her third novel, The Lost Garden (2002), was a 2003 Canada Reads selection, a national bestseller, and was also a New York Times Notable Book of the Year. Wild Dogs (2004) won the Lambda Prize for fiction, has been optioned for film, and was produced as a stage play at CanStage in Toronto in the fall of 2008. Coventry (2008) was a national bestseller and was shortlisted for the Trillium Book Award and the Canadian Authors Association Award for Fiction. It was also a New York Times Editors’ Choice. The Reinvention of Love (2011) was longlisted for the Dublin Impac Literary Award and shortlisted for the Canadian Authors Association Award for Fiction.

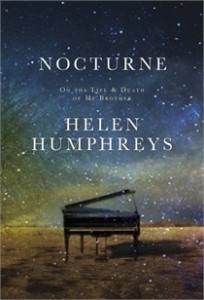

Humphreys’ work of creative non-fiction, The Frozen Thames (2007), was a #1 national bestseller. Her collections of poetry include Gods and Other Mortals (1986); Nuns Looking Anxious, Listening to Radios (1990); and The Perils of Geography (1995). Her most recent collection, Anthem (1999), won the Canadian Authors Association Award for Poetry. Her most recent work of nonfiction is Nocturne (2013), a memoir about the life and death of her brother, Martin.

In 2009 Helen Humphreys was awarded the Harbourfront Festival Prize for literary excellence.

My students and I welcomed Helen as guest author for a session of my online course Memories into Story: Life Writing (University of Toronto, SCS). What follows is an edited version of the class’s collaborative interview about Helen’s memoir Nocturne: On the Life and Death of My Brother.

“I wrote [Nocturne] because I translate lived experience into words. That is my training and my vocation. I don’t know how not to write about things that happen to me.” — Helen Humphreys

Was your writing process for Nocturne different than for your other books? If so, how?

Was your writing process for Nocturne different than for your other books? If so, how?

The writing process for Nocturne was completely different. Usually I write fiction and usually it is historically based, so there is a vast amount of research required to lift a story off the page. This is a very orchestrated procedure, very planned. Because Nocturne began as a letter, I wrote it very spontaneously, when I had something to say to [my brother] Martin. I had no plan. I just put down what I felt I wanted to say and then stopped when I had run out of things to say. Often I wrote it late at night, sitting in a chair by my bedroom window, not sitting at a desk or keeping regular working hours as I tend to do for my other books.

How did you decide which memories or stories you would include?

I just wrote them down in the order they occurred to me. I didn’t have a plan. A memory would swim up into my consciousness and I would write it down. I wanted the book to show the process of grieving, how the grief-mind circles around various events, how it doesn’t move chronologically or in a linear fashion.

How did you develop your structure?

My structure evolved naturally. I wasn’t actually thinking of publishing when I started to write it. I simply wanted to write a letter to my brother one last time, to let him know what had happened after he died. The only structural thing I did was to make 45 sections to the book, one for each year that my brother was alive. The danger of writing something so personal is to overthink it, to impose a structure on it that perhaps it can’t bear, so I would suggest to you that you just follow your instincts. What is it you want to say and what do you feel is the most natural way for you to tell the story? Trust what feels natural and then see what sort of structure naturally evolves from there.

Over what period of time did you write Nocturne?

I wrote it over six months. From late winter/early spring to late fall. For some of that time I was on tour for my novel The Reinvention of Love, and so I wrote from the places the tour took me – Italy, Banff, Vancouver.

Did you experience catharsis in creating this loving memoir?

As I mentioned, the memoir began simply as a letter to my dead brother. I wanted to talk to him one last time, and to put down some of my memories of him before they faded with time, before my life moved me too far away from his death. It was a painful thing to write, and yet it was helpful too. I wouldn’t say it was cathartic, because the pain of his death didn’t lessen, but it was comforting to be with him in this way one final time.

Did you need to tell the story of you and your brother because you’re a writer, or to deal with his death?

Probably both. I am a writer so that is how I express myself, and that is how I absorb what has happened to me, by writing about it. I didn’t write the book as therapy. I wrote it because I translate lived experience into words. That is my training and my vocation. I don’t know how not to write about things that happen to me. Also, because my brother was also an artist, it felt like a very natural way to reach out to him. Even though he was dead, our artistic conversation had not stopped.

In class, we have talked about the challenges of recreating scenes from memory. Do you have a photographic memory, or do you use your imagination when recreating scenes? For example, I am thinking of the scene in which you were allowed to hold your baby brother in the taxi on the way home from the hospital. The details about that day are extremely vivid.

I am lucky in that I have a pretty good memory that is somewhat photographic. But memory improves by exercising it and as a writer you are constantly forced to develop your powers of observation, and this in turn helps to keep your memory sharp. Also, we tend to remember things that were important to us; the day my brother was born was a very important day for me and so the memory has stayed with me.

How essential is it to remember details and descriptions, for example of a setting? I find it very hard to remember details when writing about a memory. How can I improve?

The power of observation is one of the great tools of the writer, but it is a learned power, not one that comes fully formed. So, I would suggest practising. You could treat it like an exercise and do it once a day. Leave a room, or coffee shop, or bar, and then write down what you remember about it. I guarantee you will get better at remembering what was in that room.

When we review each other’s writing in this class, I sometimes find it difficult to critique pieces about loss and suffering. It feels wrong to ask someone to provide more detail, or to suggest that an analogy they used does not quite fit, when they are writing about something so raw and personal. What was your experience with receiving editorial feedback on Nocturne? Was it different from receiving feedback on your novels?

Yes, it was very different. When one writes something intensely personal then it is hard to not take any criticism personally. But even the most personal stories of loss and death have to be interesting as stories, and I tried always to remember this.

How did your family or loved ones react to your writing the story of your brother for the public to read?

They were fine with it. We were all involved with my brother’s death and we all felt our own particular grief, but I tried to keep the book on my own grief and not presume, or speak to, anyone else’s.

You wrote about reading your brother’s e-mails. Would you ever write about what was in those? Is it considered unethical since they are not your own secrets to share?

It was my choice to respect my brother’s privacy, even in death. Someone else might have chosen to disclose the content of the e-mails, but I was writing about my grief and also about our relationship, and so, as Martin’s older sister, I still felt compelled to protect him, even from my own writing process. I don’t know if ethics comes into it at all. I think it’s merely a choice of the author as to what they are telling or not telling.

When turning history into fiction, as you’ve done in your other novels, are there standards you follow to avoid libel, or does the label “fiction” give licence?

By saying that something is “fiction” you have a lot of leeway in terms of what you write about a character. You can basically do what you want. I know there are authors who change the facts of a historical figure’s real life when they write about them because it better suits their story. I feel more tied to the actual events and try to not make too much up, but the thing is that if you weren’t actually there for an event, then all of it, no matter how closely you try to stick to the “facts,” is essentially fiction.

In memoir there is generally one voice. In the historical novel The Reinvention of Love, how did you create voices for multiple characters?

Because Charles Sainte-Beuve was a writer, I read his poems and diaries and essays. This helped enormously with setting the right tone for his voice, because I could simply imitate his real voice and slide into his character that way. What I keep in mind when creating characters is to know what their motivations are: What do they want? From life, from other people, from experience. If you know what someone wants, then you will know how they will behave in any given situation.

In Nocturne, how do you communicate such raw emotion and the depth of your grief without having your readers dissolve into tears? I’ve heard criticism of other writers’ work that it “manipulates” the reader. How can writers evoke emotion without being seen to manipulate?

I think that if a writer expresses an emotion they are actually feeling, then it will not be seen to be manipulative. When a writer constructs a text without feeling any of it themselves, to create an effect on the reader, then that could be considered manipulative. But really, all writing is trying to create an effect on a reader. There are no dos and don’ts to any of it, but I think that writing that is honest and unsentimental is more effective than writing that is not.

You write in Nocturne about Virginia Woolf and her family and how they view her writing. You write, “It’s hard to be objective about someone you know.” Who critiques your work? How do you get them to give you honest comments? Is it harder to be edited once you’ve had acclaim?

No one sees my work until I’ve been through at least three drafts and can no longer be objective about it, can’t see what else needs to be done. I’m a fairly good critic of my own work, I think, and would rather trust my own judgment in the early drafts as a writer is very vulnerable then and the least bit of criticism from outside can throw you off your path. But when I can no longer judge the merits of what I’m doing, I will show my work to my agent. An agent is not emotionally invested in the client’s writing. The agent’s job is to sell the work, so my agent will have good advice on what is working and not working in my story. She will suggest changes to the text which I will make before showing the manuscript to my editor. I don’t think I’m edited any differently now than I was when I started writing. I have very good editors, who are interested, as I am, in making the manuscript the best it can be. Their suggestions are considered and usually very wise and I always listen to what they have to say and generally follow their advice.

Toni Morrison has said, “By now I know how to get to that place where something [writing] is working. Now I know better how to throw away things that are not useful.” How have you learned to know what is/works best, what to throw away in the editing process, and when to stop fiddling with your work?

I believe now that writing that comes fairly effortlessly is the best writing and that anything that is too much hard work probably isn’t working. So I look for what comes easy, what comes naturally, and I try to move in that direction. When I’m editing I try to be fairly ruthless about the material and I’m always asking myself, Does this serve the story? And if it doesn’t, then out it goes. On the question of fiddling with your work, well, this can go on endlessly, so at some point you just have to call it quits. When you have read your work over and over again, so many times that you can no longer be objective about it, then you should stop.

I’m better at editing my own work than I used to be, but I still need an editor because at a certain point in the process I lose objectivity and need the clean, clear eye of an editor to help me to see what is there and what needs to be there in the story. Nocturne wasn’t very heavily edited because it was felt that too much editing would alter the organic nature of the narrative.

Is there a risk that in repeated editing you begin to dilute content and lose impact?

Absolutely, so you and your editor have to keep this in mind during the editing process. You don’t want to end up with something so polished that all the naturalness is gone. It is a fine balance between making something clearer in editing and taking away its full meaning. It’s good to discuss with your editor beforehand as to what both of your ideas are about the book before the editing begins; that way you can reach some sort of agreement as to what the book is about and that will help to preserve the integrity of the text when you begin to dissemble it.

Why is your memoir titled True Story in the U.K.? Do you find readership in Europe different than readership in Canada?

The original title for the book was “True Story.” The Canadian publisher didn’t like the title and so it was changed to Nocturne, but the Brits didn’t think that title would do well in their marketplace, so they kept the original title. And yes, readers in Europe are very different than readers in Canada. I can’t speak for all European countries, but I can say that the Italians in particular really liked the expression of emotion in Nocturne.

In Allyson’s memoir writing course we have been discussing emotional truth. What does emotional truth mean to you, in the context of your own novels and your memoir?

Emotional truth is everything. If you aren’t honest, you won’t write anything worth reading. So, first you have to be honest with yourself, and then you have to be honest in what you write.

In one of your interviews, you mentioned it was difficult to get back to fiction after writing Nocturne. What felt different?

There was a liberating aspect to writing Nocturne, to just writing directly from my life without any artifice. It has been hard to get inside the mechanical horse of fiction again, but I am finally back there and comfortable again with telling a story, with making one up.

Note from Allyson: The next session of my online course Memories into Story: Life Writing I, at University of Toronto SCS, runs May 5 to July 12, 2014 (10 weeks). My guest author will be acclaimed American novelist and memoirist Lee Martin. Memories into Story I is an introductory course and may be taken as a credit toward a Certificate in Creative Writing.

This is such an interesting, illuminating and also helpful piece, full of great thoughts about writing in general and writing from memory in particular. Allyson, thank you for the interview; Helen, thank you so much for sharing all of this.

I read Humphreys’ Nocturne yesterday. I was interested to learn that for Humphreys it was like writing a last letter to her brother. It felt that way when reading it; like a privilege of intimacy, as if the author was speaking to me, alone. I too grew up near the Scarborough Bluffs and until 2 years old my first home in the area was near The Guildwood Inn. I felt a strong connection to that setting, as it was mentioned a few times over the forty-five chapters. The writing and remembrances were a touching tribute to a sister/brother friendship and love.