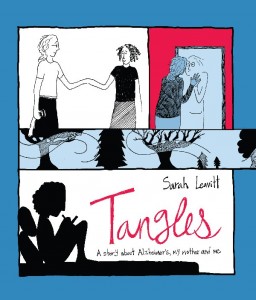

Vancouver writer, cartoonist and editor Sarah Leavitt is the author of the graphic memoir Tangles: A Story About Alzheimer’s, My Mother, and Me (Freehand Books, 2010). Her first book garnered favourable reviews and has gone on to be a finalist in several literary competitions. Sarah spoke with me recently about the process of untangling the poignant personal story that became Tangles.

A: Congratulations on Tangles being selected as a finalist for the Writers’ Trust Nonfiction Prize—what an honour that it was the first graphic work ever chosen. It’s also a finalist for the BC Book Prize and the Alberta Readers’ Choice Award, and recently won a CBC Bookie in the graphic novel category. Were you surprised by the positive reception?

S: Yes, I was surprised! But I think comics can be a powerful medium, and this becomes clear as soon as you start reading them.

A: What do you believe a reader gains from a graphic memoir that he or she wouldn’t from a traditional one? Or did your approach have more to do with the way you felt you could best express yourself?

S: Yes, I’d have to say that I started more from a place of choosing the best way to express myself, as opposed to thinking about the reader. That came later. As it often does. So when my first readers, and then my editor, read it, I started to understand a) the rewrites/redraws I needed to do in order to make the book comprehensible or useful for anyone besides myself and b) the ways in which my sketchy little drawings and stories did work, and in fact really got to people. I am still absorbing that, as I get e-mails from readers, or people come up to me after readings. And it’s thrilling and sometimes mysterious to me, that process of creating something and sharing it, and then some stranger finding it and consuming it and being deeply moved by it. To me, there are few things that are more satisfying or pleasurable.

What does the reader gain? I think that drawings can express things that words cannot, and that the combination of drawings and words in sequence (i.e., comics) communicates with the reader in a way that writing or images alone cannot. A small, gestural drawing can carry great weight. It’s related to what Scott McCloud says about comics, about how the simpler a drawing is, the more a reader can insert themselves into it. I am most interested in comics that combine simple drawings with clear simple text and a strong storyline, and this is what I strive for in my own work.

A: How did you know this was the best way to tell this particular story?

S: Overall, it just felt right. I have drawn all my life, and I had made sketches throughout my mother’s illness, right up to the night before she died, when I drew her on her deathbed with her sister sitting beside her. I had started getting more interested in making comics during her illness as well—I had done a comic that was published in Geist—a collection of the dumb things people said to me, my sister, and my dad when they found out she was ill. My other comics were all about slightly less intense topics, like small dogs and their various quirks. But for some reason I believed I could write a whole book-length graphic memoir about my mother dying. Or at least I thought so more than 50 percent of the time, which got me through the many hours of being convinced I would never finish it or that I would finish it and it would be horrible and no one would publish it.

A: Were there moments, then, when you felt that you wouldn’t be able to capture your mother’s and your family’s experience the way you hoped? How did you convince yourself to press on?

S: Honestly, there were a million moments like that. Either I cried and whined to my partner and she patiently reassured me, or I just kind of gritted my teeth and said to myself that I needed to at least finish it, and if it was a piece of shit when I was done I would deal with it then. But I needed to finish it.

A: Did writing about your mother’s illness ever make you feel sad to the point you wondered if you could finish?

S: No . . . I mean, I was sad anyway. I still am sad. The hardest part is the actual writing, and trying to make something good enough. That was what sometimes made me want to give up.

A: How did you begin? Did you create a series of written scenes first, or a storyboard? Did graphics sometimes come to you before words?

S: A mixture. I’d written a lot of the book as prose before I decided to create a graphic narrative, so I used that. And then there were other chapters where the images came to me first, like Psycho Killer, which started with more of an image of my mom as this scary demon when she was angry. Also some of the panels that I did about my mother losing her sense of smell and taste began as images in my head, and the words came later. Still other pages I planned out with a script and storyboard.

A: Did it take time to decide where you wanted the story to begin, or was that clear to you right away?

S: I originally envisioned a more complicated narrative, which sort of fell apart in my hands. I wanted to braid three threads together: the story of Mom’s illness, me falling in love (which happened at the same time) and then the Biblical story of Miriam. My mom’s name was Miriam, and I felt that there was a connection between her and the Biblical story of Miriam being struck with leprosy and shunned. But I couldn’t hold the pieces together in a coherent way. So I ended up sticking with the story of my mom, and basically starting at the beginning and working through to the inevitable end. And I knew from early on that I wanted the first chapter to be a combination of my mother comforting me when I had nightmares as a child, and then a sort of prophetic nightmare I had a few years before she got sick, but she wasn’t there to comfort me.

A: As an editor I know how much goes into structuring a narrative. What further considerations are there in shaping a book that includes graphics as well—choosing which details should be in the narrative and which in the graphics?

S: For me, a lot of that is done through intuition and trial and error. I don’t know that I could explain how I made those choices. I really think a lot of it was trying and seeing what worked and forcing myself to be honest when something needed to be thrown out and done again completely differently.

A: There’s an effective alchemy when a graphic is in counterpoint to the narrative that accompanies it—for example, the graphic seeming humorous but the narrative serious, or vice versa. That’s something this form offers that a traditional memoir doesn’t. Did that mean more complicated decisions for you as author/artist, or simply open up possibilities?

S: Oh it does both: makes your life hell and opens up huge vast areas of possibility. But how gratifying! The best thing a reader can say to me is that they were laughing and crying at the same time when they read my book. I love that. And it is a goal of mine, to make readers do that – I think it’s just how I tend to tell stories. And yes, graphic narrative is perfect for that. Perfect for forcing readers to feel many things at once.

A: You have a wonderful eye for small but telling detail. Is that the artist in you, or the writer, or a bit of both? Do you feel that caring for your mom and recording details made you more attentive to details in life generally?

S: Thank you! I have always noticed details and something I try to do in my writing and comics is to choose the right details to convey the emotion or meaning that I want to convey. That is so hard! I think writers and artists do tend to notice details, and often our challenge is to cut out excessive details that do not serve the story. And yes, spending time with someone with dementia, whose world is very small, does make you notice the details, the small things about food or pets or flowers that people with dementia notice in a different way from most people.

A: In your Introduction you say that it took four years to create your manuscript. How much revising and editing was required after that?

S: I did two rewrites before I sold it, and then did a few rounds of edits with my publisher after I sold it.

A: What research did you do? And did it involve your reading other graphic books?

S: I had to do a bunch of research about my mom’s family and details of my own childhood that were blurry for me. And I was careful to confirm the facts I put in about diagnosing Alzheimer’s. And I read tons of books. My favourite cartoonists include Art Spiegelman, David B, Lynda Barry, Marjane Satrapi, Aline Kominsky Crumb, Miriam Engleberg, Brian Fies . . . I read a lot of autobiographical comics, especially about illness or tragedy.

A: Do you think the fact there was humour amid such sadness was a revelation to some readers?

S: It doesn’t seem to surprise anyone who has been through this kind of experience, because they know that laughter creeps in all the time in spite of everything, or because of everything.

A: Was it sometimes a challenge to find the right balance between writing honestly and maintaining the dignity of your family?

S: Yes.

A: You must have had to think of your family members and friends—your father, your sister, your aunts, your partner—as “characters” in order to craft your story. How did you go about “getting them right”?

S: Yes I did have to think of them as characters. And what was most helpful in that regard was outside feedback from people who didn’t know them, like my editor at Freehand who would say, “Why is your dad doing that when in the last chapter he did this?” It helped me step back a ways and see that they needed to have clear motives and be consistent, and that the reader needed help to understand things that I just had known all my life from growing up with these people. And I had to do things like cut out a lot of stuff about my partner, because although she is central to my life, and was a central part of me surviving my mom’s illness and death, she was not a main character in this particular story.

A: How did you decide how much of your personal struggle to include? There are only brief, gut-wrenching references to your wanting to drive into oncoming traffic, or cut yourself—glimpses into what you were dealing with emotionally. Another writer might have focused more on this.

S: This is another area where I had to edit out a lot of stuff. Believe me, there used to be a lot more about my own suffering. But my most respected teachers (Mary Schendlinger, Stephen Osborne) have taught me to get out of the way of the reader. Not that you don’t write about yourself, but that you leave as much space as possible for the reader to experience the story without your editorial comments.

A: Did what you wanted the reader to take away from Tangles evolve over the course of the writing?

S: Hmm, I’m not sure. What I wanted from the beginning was to create a tangible record of my mother’s illness, sort of a report back from the front lines of a strange and horrible experience. A lot of readers have said that they see the book as a record of my mother both before and during her illness, a tribute to her. This was not my intention, but I am glad to hear it.

A: You write in your Introduction that your mother’s decline forced you to recreate your relationship with her. Did writing the memoir, too, involve an element of recreation of your relationship with her? With others in your family?

S: I don’t know if it recreated my relationship with my mother. Although I do think there is a way in which writing memoir creates another reality—that is, there is what really happened and then the way you tell the story—as many writers have said far more articulately than I just did. I think in some ways the book has brought me closer to my father and sister, as they have been really positive, supportive and grateful for the book in ways that I did not anticipate. Perhaps it helped us understand each other better.

A: Did you show the manuscript to family before submitting it for publishing? Were there any unexpected reactions—good or bad? Did you change anything as a result?

S: I showed parts of it to my dad, but I was very determined not to do it in order to get approval or ask permission, but because a) he was there and I wondered what he thought of how I remembered things and b) he is very smart and well-read. He liked the pages I showed to him. I never showed my sister because I thought she wouldn’t like it and I was worried she would tell me to change things or not write about them. I was shocked when she read it after it was published and loved it. My dad has been enthusiastic and generous and loving about the book beyond what I could have expected. But yeah, I purposely did not show them the book until it was too late for them to do anything about it.

A: Have you had any memorable feedback from readers?

S: I’ve gotten a lot of e-mails from readers. Each time a stranger reads my book and talks to me about it is memorable, because for some reason I still haven’t gotten used to it. A number of people have told me they read the book many times in a row, that it comforted them somehow. Some people in their seventies or older have said that they didn’t think they’d like a comic book, but then they tried it, and they loved it. My dad’s mother and my mom’s stepmother are both in their nineties and they read it and loved it. I like that. I like it when people read the book who don’t usually read comics. And then I start telling them about all the other comics they have to read!

A: Do you feel the experience of writing Tangles changed you in any way?

S: It made me feel older, somehow. I don’t know, maybe because I looked back on my life and that’s something an older person does. Or because people talk to me like I know something. Or maybe it’s just because I’m a woman in her forties writing comics and just getting my start so late . . . It made me more obsessed with comics too.

A: I hope you have another book in the works?

S: Yes! Historical fiction. Dark, violent, suspenseful. Nothing to do with my own family. It will be a huge challenge. But I am extremely excited.

SARAH LEAVITT has been interviewed on national radio—CBC’s The Next Chapter and Definitely Not the Opera—as well as local radio and television programs. She has also been a featured reader at literary festivals in BC and Alberta. Sarah will be touring Ontario in the spring of 2011, and begin teaching in the Creative Writing Department at the University of British Columbia in 2011/12. The UK/Commonwealth rights to Tangles have been sold to Jonathan Cape for publication in 2011.