A couple of weeks ago I posted a quote from Lucy Maud Montgomery’s autobiography The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career, along with three exercise questions to encourage you to write about a place, or places, special in your memory.

Sandra Shaw Homer liked the idea, and surprised me by sending in the following engaging short reminiscence, which I’m now sharing with you. A writer and resident of Costa Rica, Sandy was guest speaker for my Namaste Gardens writers’ retreat in 2012.

Perhaps Sandy’s recollections will in turn trigger memories in you. If so, well, don’t just think ′em; write ′em!

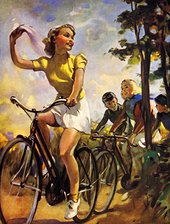

Credit: Image Courtesy of The Advertising Archives

Bicycle Summers

Katie Smith lived about a half-mile down the road on the other side of the bridge that spanned the widest, darkest pool in the creek, and she was just my age. We lived on our bicycles when we were 12 — that is, when we weren’t building snow forts to protect us from Bobby Benner’s ice-filled snowballs or creating our imaginary garden on the sandbar downstream.

The Benners lived in a log cabin at the end of the dirt road that angled away from the pool just before the bridge. I only saw the inside of that cabin once — perhaps on a chilly Halloween night — and I remember the white plaster starkly outlined against the old black logs — who knew how old that place was? — and a smell of generations of endless woodstove winters. I thought at the time that it would be interesting to know those people better, but Bobby Benner, being older than Katie and me, was our enemy and constant tormentor.

The only time we were safe from him was when we were skating on the pool, all our parents huddled around the bonfire on the bank, smoking cigarettes and sipping whiskey out of dented flasks that they kept mostly hidden in their pockets. When a child fell down, a parent would come waddling out onto the ice in well-stuffed rubber boots to haul him or her upright. Sometimes the adult would skid and fall, and then it was mayhem.

Katie and I attended the sixth grade at Macungie Twsp School. That’s what it said in big letters right across the side of the red brick six-classroom building. My mother thought this was funny, and so we always called it the “macungietwispschool.” Only later did I learn what a “township” was. This was rural Pennsylvania, and most of children were farm kids, not always regular attendants.

Right across the road from us was the Lichtenwalner place, century-old house, bank barn and outbuildings all facing each other like circling wagons. This made it convenient to get from one place to another in winter weather. From the Lichtenwalners we bought our eggs, and once I was invited for a hog killing. The screaming impressed me, and I left before the butchering began. I think I had been invited by David Lichtenwalner, a couple of years my senior, who had a crush on me. But I had already been taught to be a perfect snob.

In rainy weather, Katie, my younger sister, and a small neighbor boy named Lyn and I played in our own bank barn. In Pennsylvania Dutch country a bank barn is simply one built into a slope, with the stables for livestock at the semi-underground level, and a cavernous dusty space above, reachable by an earth bank at the back (or a trap door and ladder from below). The base of our barn was built of fieldstone, the storage space above of wood and the roof slates hauled a century past from some nearby river. In haying time, that storage space would fill with carefully stacked wire-bound bales of hay. In summer it would empty and nothing remained for us children to do on a rainy day except scamper up and down the ladders and across long-smoothed, hand-hewn 12-inch wooden beams, playing tag with a basketball. Our mother never knew.

In spite of the fact that it wasn’t a mile from our house to the school, county school board regulations required that I travel to and fro by bus. And, for the most unfathomable reason, the bus would turn right at the Lichtenwalner place and wander around the countryside until it got to Katie’s house (the next-to-last stop on the 45-minute run) and finally mine. Being the last ones off the bus gave us many opportunities to cement our friendship and “make plans.”

Although, we got into an argument once, and we were still of an age to feel we needed to settle it physically. I jumped off the bus right behind her and pulled her to the ground, pummeling her as best I could, with her elbows fending me off. Even though her mother was outside in seconds, screaming and pulling us apart, I already felt how absurd it was to be physically fighting with my best friend, and I wanted to laugh. It was only the one time, and we made up, but was the damage ever undone?

Bicycle summers. Those are what I remember best. We could go for miles on those back-country asphalt roads, the sun high, the sky a breezy blue, the dusty, sharp smell of corn, alfalfa and hay rising from the fields on either side of us, sitting high on our saddles, or leaning forward in a make-believe race, no one to worry about where we were going or what we did. That was freedom.

♦ ♦ ♦

SANDRA SHAW HOMER has lived in Costa Rica for more than 20 years, where she has taught languages and worked as an interpreter/translator and environmental activist. Between 1997 and 2000 she wrote a regular column, “Local Color,” for the English-language weekly The Tico Times. She became a Costa Rican citizen in 2002. In a previous life she headed her own public relations firm in Philadelphia and wrote occasional articles for the local business press. Her writing has appeared on a couple of blogs, notably Living Abroad in Costa Rica.