Years later, I couldn’t wait to read the trilogy to my own boys, and when I did, they enjoyed them too — not least, I suspect, because of my enthusiasm — despite a style of writing more formal and old-fashioned than what they were used to in most children’s books my husband and I read to them.

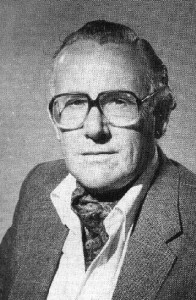

Samuel Youd was a prolific author known for the science fiction he published under the name John Christopher, but in all he penned more than 60 novels of science-fiction, thrillers, historical romantics, detective stories, and comedies. He is best remembered for his “Tripods” trilogy (1967 — 1968) and two other trilogies for young adults, “The Sword of the Spirits” (1970 — 1972) and “The Fireball” (1981 — 1986), and for the novel The Death of Grass (1956; published in the U.S. as No Blade of Grass.) He also wrote under the names Hilary Ford, William Godfrey, Peter Graaf; William Vine, Peter Nichols and Anthony Rye. To further confuse things, while his birth name was Sam Youd, he adopted the name Christopher Samuel Youd as a professional name.

Youd was born in Knowsley, Lancashire, England, on April 16, 1922. His father was a factory worker and his mother a cook in the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. When Youd was 10, his family moved to Hampshire and he attended Peter Symonds School in Winchester. About that time, he became interested in writing and in his teens started an amateur magazine called The Fantast. He served in the Royal Signals Corps between 1941 and 1946, and married soon after his release.

As Youd struggled to support his growing family, he worked at an office job while writing during the evenings and on weekends. A Rockefeller Foundation scholarship helped him to complete The Winter Swan (1949). He wrote at a remarkable pace, completing 10 adult novels and numerous short science-fiction stories for magazines over a 9-year period. (He wrote The Choice [1961; later published as The Burning Bird], an adult novel, in about four weeks, and during some years turned out as many as four manuscripts.) His first major success was the novel The Death of Grass (1956), written under the name John Christopher. Only after its publication did he begin making enough money to begin writing full time.

He was influenced by the short fiction appearing in U.S. magazines of the period, including that of John Wyndham, Arthur C. Clarke, Aldous Huxley and Kingsley Amis. But in a 1999 interview with Colin Brockhurst, he spoke of another novelist he admired, Jane Austen: “I very strongly feel that the important and useful exercises of imagination are related to ‘the human condition’ — that Jane Austen’s imagination is stretched at a far higher level than, for instance, Arthur C. Clarke’s (sorry, Arthur). To me in my late years it seems evident that relationships are the root of existence, scientific extrapolation a pleasant toy.”

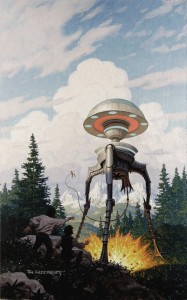

The White Mountains (1967) was Christopher/Youd’s first young-adult novel, a response to a publisher’s suggestion that he aim for a younger market. In the story, human beings have been enslaved by aliens who remain hidden from view as they move about in looming three-legged walking-machines. Society is anachronistic, with humans living in villages reminiscent of the Middle Ages but using inventions from later times. From age 14, people are controlled by implants called “caps,” which mute human characteristics such as curiosity and creativity and render people incapable of independent thought or rebellion. Will, his cousin Henry, and another boy they meet, Jean-Paul (Beanpole), run away before their capping. Their quest is to reach the White Mountains, and freedom.

Before writing The White Mountains, Youd claimed, he wrote all his books in a single draft, only ever rewriting the first chapter after completing the rest of the book. But that changed when he came under the influence of Susan Hirschman, a talented editor at Macmillan, his New York publisher. Here’s what Youd told Colin Brockhurst about this editing experience:

“I wrote The White Mountains, and [agent] Dick Hough accepted it…. It went to my U.S. agent, who sent it to Macmillan. Susan Hirschman, their editor, wrote a long letter which he sent on: she said it started great and then fell apart. I thought of telling her to get stuffed, then looked at the book again, and realized I’d been thinking ‘Well, it’s just a children’s book.’ So I rewrote after Chapter 1. She said the middle was still wrong, and I rewrote again. Dick Hough accepted all three versions as they came along. That was when I began to realize that, in the right hands, editing a children’s book was much more serious than in general fiction (by that time I suppose I’d had close on twenty adult novels published). On City of Gold and Lead, she just required a rewrite of the opening. On Pool of Fire, she cabled ‘Great!’ to the first draft. I thought I had it licked. I went into The Lotus Cave with confidence … and she told me it was a mess. I said OK, write it off. She wouldn’t have that. By now a great pal of Julia McRae, who’d replaced [agent] Dick Hough, she flew to London, had me flown over from Gurensey, and sat us all three down in Julia’s Bayswater flat with the grim message that no-one would move until we got a solution. Julia put in the breakthrough, hence my dedications of the U.K. and U.S. editions to Susan ‘for flying to the rescue,’ and to Julia ‘for the spark that broke the log-jam.'”

Like many writers, Youd sometimes wrote from personal experience. The White Mountains at the end of his narrator’s long and dangerous journey were the Bernese Alps, between the cantons of Valais and Bern in Switzerland. The author had lived with his family in Switzerland in 1958/59 and had been impressed by a trip up to the Jungfraujoch, a col between two of the three highest peaks, Mönch and Jungfrau.

After writing The White Mountains, Youd returned only occasionally to adult fiction. “The young adult audience basically satisfied me,” he told Brockhurst. “It was reasonably successful and provided much more feedback than the adult did.” Over the years he was honoured with many literary awards including the Rockefeller-Atlantic Award in Literature, 1946; the Christopher Award, Books for Young People category, 1971; the Guardian Children’s Fiction Prize, 1971; the Deutscher Jugendliteraturpreis (German Youth Literature Prize), 1976; and the George G. Stone Center for Children’s Books Award, 1977.

Asked by Brockhurst what advice he would give to aspiring writers, Youd said,

“… you just have to keep at it. The Winter Swan [1949] was sold to the first publisher who read it — as I later realized, a fluke. My second novel went the rounds for over two years before being taken by the firm that had already taken my third. When children ask me this, I offer two suggestions: to read as widely as possible (not just what takes your fancy) and to practise continuously, through a diary if nothing more constructive comes to mind. What you need most of all is stamina. Apart from luck, that is.”

Sam Youd — who will always be John Christopher to me — died on February 3, 2012, at age 89. He leaves behind five children, a remarkable body of work that spans five genres, and generations of fans.

* * *

For more about Sam Youd, read Colin Brockhurst’s extensive Interview with “Tripods” Author Sam Youd (a.k.a. John Christopher) and his article for Circus 8, “The Shattered Worlds of John Christopher.”

Loved this Allyson, especially “in my late years it seems evident that relationships are the root of existence.” Wonderful how that grade 5 experience has stuck with you through all these years. We’ll have to check out the trilogy!