Credit: Jennifer Hendry

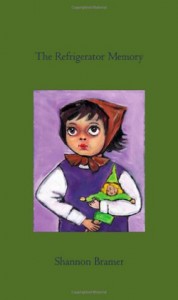

SHANNON BRAMER is a poet and playwright. Her poetry collection The Refrigerator Memory was published in 2005 by Coach House Books. Two previous poetry collections, suitcases and other poems and Scarf, were published by Exile Books. Shannon’s first play, MonaRita, was produced in St. John’s, Newfoundland, in February 2010 and has since appeared in festivals across the country. Sometimes you can find Shannon in the playground, recruiting little poets: www.poetintheplayground.blogspot.com.

Shannon, when did you know that you wanted to be a poet?

When I read Irving Layton’s poem “Song for Naomi,” in grade 6. I didn’t know I wanted to be a poet then, but I so badly wanted that poem to be mine. So I copied it out in my own handwriting, changed the title to “Song for Shannon” and told my mother I wrote it. I let her believe I was a genius for a few days and then told her the truth.

How old were you when you wrote your own first poem, and what was it about?

I started writing poetry when I was nine years old. I wrote about love and nature and loneliness; I wrote lots of anti-war poems as well. I grew up listening to a lot of John Lennon records and the Beatles thanks to a girlfriend of my father who loved music. I think I internalized a lot of those songs.

You’ve written other forms as well. Do you prefer poetry?

I don’t think I prefer poetry; poems are the hardest for me to write. Poetry is medicinal. I need to read poetry and I crave poetry in a way that I don’t other forms of writing. I do write fiction and nonfiction and plays, and always there is some poetry inside, I hope.

In what ways do ideas for poems usually come to you?

Often a line comes into my head that wants to be written down, a line or a title. Like: Helena the Fox. I don’t know what the poem will be yet but I really want to write a poem and call it “Helena the Fox.” I do a lot of automatic writing*, a technique developed by the Surrealists, because it helps me find things inside that I want to dig out and write down.

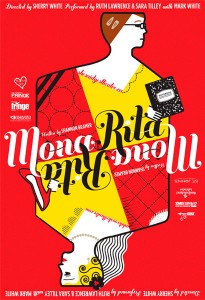

Where did the idea come from for your play, MonaRita, and how did it develop?

Monarita started off as a strange conversation in my head that became more complex and alive as time went on and so I had to write it down. It’s a play that explores intimacy and identity via two characters: Mona and Rita. It flirts with realism but is really an absurd play. Imagine two women on stage wrestling with each other literally and emotionally, add in some foot massages and a dance number, and you have my MonaRita! I had a brilliant cast from St. John’s, Newfoundland, produce and tour the show last year and fortunately the reviews were fantastic. The driving forces behind MonaRita were She Said Yes! and White Rooster Theatre. I have two other completed plays, and I’m working on another. They are all “dark comedies.”

Monarita started off as a strange conversation in my head that became more complex and alive as time went on and so I had to write it down. It’s a play that explores intimacy and identity via two characters: Mona and Rita. It flirts with realism but is really an absurd play. Imagine two women on stage wrestling with each other literally and emotionally, add in some foot massages and a dance number, and you have my MonaRita! I had a brilliant cast from St. John’s, Newfoundland, produce and tour the show last year and fortunately the reviews were fantastic. The driving forces behind MonaRita were She Said Yes! and White Rooster Theatre. I have two other completed plays, and I’m working on another. They are all “dark comedies.”

How much would a reader learn or understand about you personally by reading your poems? Are all or most of them semi-autobiographical?

There are many clues to my personal life in my poems: how much I love music, fairy tales, fancy food ingredients. A person closely reading my work would probably get the feeling that I’ve suffered some significant losses in my life, that I’ve been in love, that my childhood was rich and complicated. Ultimately, though, my poems are not autobiographical. I love to invent characters, create voices and move words around on the page like the pieces of a puzzle. When I’m teaching I tell my students that my poems are all 100% fact and 100% fiction. I make sure they know that their own poems need not be autobiographical; I emphasize this because many of my poems are deeply personal and I don’t want to promote one way of seeing or thinking about poetry.

Have you written personal essays or short memoirs?

I love the essay form and especially the hybrid essay-poem (the kind Anne Carson and Phil Hall write!). I never seem to be able to write anything that sticks to the memoir form exclusively. The essays and short pieces of writing that draw directly from my life are almost always infused with some imagined and/or made-up details. My fidelity is to the shape and sound of the line first of all, or the beauty of the fragments as they come together on the page.

Are your poems your memoirs, in a sense, an exploration of where you’ve come from and who you are?

I think my poems probably do function that way for me! I can remember where I was when I wrote each one of them, who was in my life, what my dreams and doubts and worries were. It’s a different sort of record, perhaps one that is more secretive and coded, but certainly one that is coherent for me as life moves along.

Do your poems ever make you feel exposed? And if so, how do you find the courage to share them?

Organizing thoughts on a page for everyone to see and question and sometimes scrutinize is quite thrilling and scary. Sometimes the subject matter is frightening, too, as with a poem I wrote many years ago called “The Molested in the Mirror.” It’s a very short little poem but it explores a subject that readers might instinctively shy away from. I think the courage comes from having a supportive publisher and also a gut feeling for the way a poem is working. If a poem is working well it’s a little easier to take an emotional risk.

Where is your favourite place to write?

I don’t have a room of my own, but I do have a little desk set up in a corner in my living room. I have an octagonal window above me with an orchid there. The cats and my children generally know not to interfere with this tiny space. I also like to write at two favourite café’s in Toronto: Crema and Agora, both in the Junction.

I don’t have a room of my own, but I do have a little desk set up in a corner in my living room. I have an octagonal window above me with an orchid there. The cats and my children generally know not to interfere with this tiny space. I also like to write at two favourite café’s in Toronto: Crema and Agora, both in the Junction.

Do you do a lot of “writing in your head,” or do you record your ideas immediately on paper?

I do both. I love my notebooks!

Are you ever blocked in writing, and if so, what do you do?

I don’t really get blocked, but I do get stuck. I feel I can’t write anything, or I feel too stupid to write. My writing embarrasses me. When this happens, I read. One book that always cheers me up is David W McFadden’s poetry collection Gypsy Guitar, a Canadian classic. When I read that book I stop taking myself so seriously and remember why I love to read and write.

What would you say are your three greatest sources of inspiration?

My daughters. Words. The Fred Eaglesmith Travelling Show.

How did your poetry evolve in the period between your first and third books?

Experiments with voice and fidelity to lyricism are still my dominant impulses as a writer. My poems have become a little more adventurous in some ways, but I think I have become a bit cowardly in my old age as I worry about what my peers think of my work. Being frozen and distracted as a writer doesn’t do much for poems—you need to allow yourself a certain recklessness to write well, I think.

Experiments with voice and fidelity to lyricism are still my dominant impulses as a writer. My poems have become a little more adventurous in some ways, but I think I have become a bit cowardly in my old age as I worry about what my peers think of my work. Being frozen and distracted as a writer doesn’t do much for poems—you need to allow yourself a certain recklessness to write well, I think.

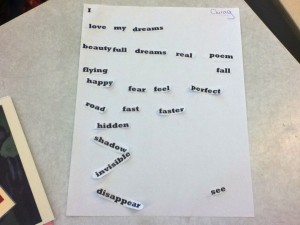

I met you — what, eight years ago? — as a very enthusiastic poetry workshop instructor for children through my sons’ elementary school. You continue, as you say, to enjoy “recruiting little poets.” What is it like, teaching children to write poetry?

Children are unpredictable. They help me see things freshly. I love being part of their lives for a little while and helping them find their way inside poems. I teach poetry as a style of being. They seem to understand me so I love being with them.

What sort of surprises do young poets offer an instructor?

They write beautiful things and make such imaginative connections. They know a lot about science, history, music, art, etc., and will bring what they know into their work. Finally, many of my students are relatively new to Canada and have intimate knowledge of places I will never see. These kids remind me of the vastness of the imagination, the internal landscape we all possess. They remind me that we are all so much more than what we present on the surface.

Do you believe that all of us have a bit of the poet inside us?

Children are born with that bit. Some have a bigger bit than others I think, but unfortunately if that little bit gets smushed out at some point it can be difficult to revive in a person. People who let their dogs poo on the sidewalk and don’t clean it up, for example, have had the poet smushed out of them at some point. Also, people who don’t give up their seats on buses for pregnant women or octogenarians, have also had their inner poet smushed.

Children are born with that bit. Some have a bigger bit than others I think, but unfortunately if that little bit gets smushed out at some point it can be difficult to revive in a person. People who let their dogs poo on the sidewalk and don’t clean it up, for example, have had the poet smushed out of them at some point. Also, people who don’t give up their seats on buses for pregnant women or octogenarians, have also had their inner poet smushed.

Your daughters are now ages 4 and 7 — are you encouraging a poetic sensibility in them?

Maybe?! We read together a lot and they know how much I love poems, music, songs. My husband is also a very disciplined writer so I think they know how much we value the act of writing beyond utility.

What is the best writing advice you were ever given?

Be specific!

Be yourself!

What is the worst?

Be political!

Be relevant!

Tell us some of your favourite things to do that don’t involve writing.

I love live music and going on little solitary adventures that involve going to hear the music I love. I also love film and photography and wish I had the time right now to learn more about those art forms. I also love cooking more than any other domestic activity. Finally, I watch a lot of Seinfeld reruns. I never get sick of Seinfeld.

What might people be surprised to know about you?

I spend a lot of time picking dry noodles off the kitchen floor. I have no sense of inner peace. I am really funny once you get to know me. I would like to be known.

What are you at work on now — and looking ahead, what are some of your literary dreams?

My latest play is called “More Blue.” I’d like to put another poetry collection out soon, and get the funding I need to continue working with kids in classrooms. I would also love to be included in a Canadian anthology of poetry. That would be a dream come true.

How would you respond to people who say, “I just don’t get poetry.”

I would say the greatest thing about poetry is that you don’t need to get it. Sometimes you might feel you do, which can be wonderful, but it’s not a necessity. I would say that getting it isn’t really the point. Sometimes I like it when a poem is challenging, when it’s strange or puzzling—other times I seek the familiar in a poem. I want to be comforted by what I read. A person who doesn’t get poetry just hasn’t found a poem yet that speaks to them directly.

*Automatic writing: Writing performed without conscious thought or deliberation, typically by means of spontaneous free association.

In the next post, “The Whiskey Stool and Other Memories,” Shannon shares stories behind four of her treasures.