From the Archives

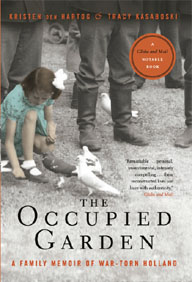

The Occupied Garden, co-written with my sister Tracy Kasaboski, tells the story of our grandparents during the Second World War in Holland. Opa was a market gardener, and grew vegetables on a huge property near the Hague — thank god, actually, because it meant that they had at least some food by the end, and that because of his “necessary” occupation he was less likely to be scooped for forced labour, at least during gardening months.

The book is a very much a hybrid. In fact it was been an enormous challenge finding just the right balance of family and objective history. When we first got notes from our in-house editor on the initial draft, we found that while she very much liked what we’d accomplished, she felt the family was being overshadowed by the larger picture, so our mission with the second draft was to pull the family forward and try to put ourselves more in their minds — and to link the big events like the Battle of Arnhem and the food embargo and so on with the personal side of things, from Oma and Opa’s perspective.

The editor sensed rightly that we were “holding back” — protecting our family and not wanting to assume too much about how Oma and Opa might have reacted to the mass round-ups of men, starvation, brutality, et cetera, endured over the course of the war. But we have fragments of stories that include Opa slipping upstairs with his coat and hat on and hiding between the walls while the Germans went door to door collecting men for forced labour — this after the gardening season was over. So our job was really a matter of setting these fragments into the history that is so well documented, and figuring out just where the fragments go, and then how the external events must have impacted the family. And once we were successful in narrowing that down, it was so rewarding, because suddenly the fragments took on more meaning.

And that really is how the whole story came together, bit by bit, moving things around and learning more about the broader history, and seeing how these little anecdotes might fall into place.

Sometimes, when absolutely nothing could be known — as was the case with whether or not Opa had been a prisoner of war immediately after the invasion — we pulled back from the story and told the reader just that, which is a reminder that the story in many ways is about the loss of stories as generations pass; the importance of preserving them; and also the way they change, grow, shrink over time. We tried to stay out of the story as much as possible, aside from a prologue and an epilogue in which we are fully present. But these few places that we “appear” seem key to me, an integral part of what cannot possibly be a complete and true recounting because the people who lived through it are gone. Oma and Opa never talked about their experiences during the war — they went through some horrific things, but their culture/era/personalities told them the best way to deal with those things was to move forward. And it didn’t occur to us to ask them, back when we still could — to really press for the details when they were still alive, because we were too young and we didn’t see the importance of knowing, or have any idea just how much there was to learn.

The time period is so dramatic, both within and outside the family, that it was difficult to know what to leave out, so that was another challenge. In many ways the book chronicles our family alongside the royal family (the queen’s daughter came to Canada with her children) and shows the striking contrast between their experiences. We did lots of research — some of the most interesting stories came from diaries by both famous and unknown people: Oma and Opa’s Jewish friend who escaped to Switzerland; a neighbour who sheltered a Jewish family; the accounts of Goebbels, William Lyon Mackenzie King, and the memoirs of Queen Wilhelmina.

The process is so different from fiction, where you can see what “needs” to happen and steer it that way. It was so strange for me to be roped in by facts and a predetermined storyline, and to discover that it is still necessary in non-fiction to determine the shape of the story, and to find the places of dramatic tension, climax, et cetera, and to sculpt the story so it’s moving cohesively toward its end. Otherwise it’s a list of facts, a recounting of anecdotes that don’t make a meaningful whole.

Kristen den Hartog is the author of three novels, Water Wings, The Perpetual Ending, and Origin of Haloes. Her most recent book, The Occupied Garden: A Family Memoir of War-Torn Holland, was written with her sister Tracy Kasaboski and explores the life of their father’s family during the Second World War. She lives in Toronto with her husband and daughter, and blogs about the books they read together at Blog of Green Gables.

This essay was originally published on Allyson Latta: Memories into Story in August 2010. Kristen has since published the novel And Me Among Them and is at work on another project with her sister Tracy. Kristen’s final post on Blog of Green Gables appeared on September 6, 2013.