“… it seemed to me that writing was something other people did, wonderful people who lived in an atmosphere of intellectual fervour where brilliant conversation was the norm, people like Virginia Woolf and her circle of erudite Bloomsbury sophisticates, not people in our humble walk of life.”

Photo: Anton Belovodchenko Anton (www.shutterstock.com/g/belovodchenko)

LEARNING TO WRITE is a long and finicky process and it’s a good idea to start early, to study English or Creative Writing at school or university where you will learn certain fundamentals. Most writers spend about twenty years developing and honing their skills before their first real publication.

Having said what you should do, I must admit that I did none of these things. I studied science at university and became a Chartered Accountant to make money. It is important to have a source of income, since writing is a notoriously stingy profession. A very few writers make gobs of money, Margaret Atwood for instance, and the author of Fifty Shades of Grey, but the rest of us scribes exist on our day jobs or the support of a long-suffering spouse, and sometimes, as our talent becomes honed, on grants from the Canada Council.

I didn’t do these things because I got off to a very late start. Why? Many reasons, such as raising our family and working to contribute a second income to the household. But other writers have coped with these roadblocks, so why did I take so long?

Looking back over the years I’ve come to realize there was one pervasive reason: I didn’t give myself permission.

§ § §

Photo: Giampiero Acri

Nobody in our family had ever tried to write. It wasn’t even a glow on the horizon of the imagination; it wasn’t a thing to be considered. From the day I learned to sound out the word cat, I was — as all writers must be — an avid reader, and I would have loved to try writing myself even then, but I didn’t because it seemed to me that writing was something other people did, wonderful people who lived in an atmosphere of intellectual fervour where brilliant conversation was the norm, people like Virginia Woolf and her circle of erudite Bloomsbury sophisticates, not people in our humble walk of life.

I was brought up on the prairies during the Depression when culture was way down the list, well below buying food and clothing and staying off relief. My mother read the sort of things I despised and I attempted to hide her books and magazines from my friends — True Romances, love stories with sappy plots. I sneered at her with all the condescension of an adolescent, while she, defensively, made fun of my propensity to read what she called those highfalutin tomes.

To add to this I had the usual adolescent female negative self-image so that even if the possibility had crossed my mind I wouldn’t have considered it in the realm of the likely that a person like me could aspire to the esoteric heights of writing. The result, because I was good at factual material in high school (and possibly to prove something) — I studied science.

Those are my reasons, or perhaps I should call them excuses, for not taking seriously my urge to write. But once when my three children were in bed and my husband was out building up his business to support us, I succumbed to the impulse to abandon the uninspiring world of diapers and runny noses and try my hand at a short story. I sent it off to Maclean’s magazine, which in the pre-blogging age published fiction. They accepted and published the story and sent me a nice little cheque.

Great, I thought, I’ll work away at these in the evenings and supplement the family income and possibly become famous.

Not so fast, reality said. You haven’t paid your dues.

I tried and tried but couldn’t follow up the first story with another winner, and eventually, as our finances dwindled with the demands of a small, undercapitalized business, I went for something easier, studying and articling to become a Chartered Accountant. In those days in a small town like Penticton you could article in the daytime and take Queen’s University courses at night. If you already had a university degree, it took four years until the final, gruelling set of Canadian standardized exams.

§ § §

I was forty when I got my degree, and by the time I had reached my late forties I suddenly found myself in Ottawa, no longer the hard-working professional with three teenagers at home, but a politician’s wife. Only one teen — Leslie — came with us when my husband was elected to parliament, and I was caught up in what passes in Ottawa as a social whirl, where the weightiest decisions were what to wear to the next function.

I soon became so bored that I decided to try writing once again, and with the foolishness of the uninitiated, thought that this time I would write a novel, since I liked novels much better than short stories. I had had a very difficult boss and so naturally I wrote a novel about a very difficult boss, which was therapeutic in its way, and called it The Manipulator. The novel was published the same month, October of 1972, that my husband lost the election and we moved to North Vancouver.

To my surprise the manuscript was picked up right away by McClelland & Stewart, but alas, it got a stinging review in the Globe and Mail. (I found out later that the reviewer was notorious for writing clever, spiteful reviews, that he eventually made the mistake of taking on Margaret Atwood, and from then on found himself no longer very much sought after.) I felt ashamed and wildly discouraged. In other words I had a lot to learn about the real world.

In spite of all this, The Manipulator won the Canadian Booksellers award for 1972. This didn’t generate much in the way of publicity, but I did get out of it a trip to Banff to pick up the prize. No one was able to come with me and see my short triumph, but Farley Mowat was there, and sensing my slight unease in the grand ballroom of the Banff Springs Hotel he went out of his way to be friendly and hospitable.

That happened at the end of June and merited a tiny footnote in the newspapers — and then everyone in Canada went on holidays as they do when the snow finally melts, and that was that.

§ § §

The next novel I tackled was loosely based on my mother, who was by then deteriorating into dementia. It was called Pretty Lady, and I worried that she might still be able to recognize herself in it. This time McClelland & Stewart passed on it — The Manipulator hadn’t sold every well — and so General Publishing took it. Unfortunately an editor there had a penchant for cutting as much as possible while still telling a story, and the graphic artist they employed got a little carried away (the cover featured a partially nude woman looking out a window onto a stormy landscape), and so the final book didn’t come out the way I had hoped. My mother died before the novel was finished, and that at least made me pause and think about the ethics of writing a roman à clef, in which the protagonist is a fairly easily recognized person of one’s acquaintance. Truman Capote did that, in a nasty way, in his unfinished Answered Prayers, and unsurprisingly ended up without any friends.

I decided to write entirely from my imagination, and this time I turned to science fiction with The Immortal Soul of Edwin Carlysle, which was again picked up by McClelland & Stewart. Nowadays science fiction is a reputable and popular genre, but in those days it was considered less respectable than literary novels, and besides, any readership I had was based on my previous literary novels. It turned out my few fans didn’t like science fiction. The novel got some good reviews, but nevertheless sank with scarcely a bubble.

And that was when I really began to learn my trade. I’ve lost track of the number of novels that ended up in a drawer — at least four — but I began to get my short stories accepted by literary magazines.

It was during this plodding phase of my career that Carol Shields came to the rescue.

§ § §

Carol and I had been friends from the time she wrote her first three novels after following the prescribed path — studying English and Creative Writing as she grew up. These first novels were alternately praised for their use of language and the deftness of their characterizations, and damned as being “housewife novels.” She broke through that stereotype with a complex mystery novel called Swann, and suddenly the literary establishment was paying attention.

Carol and I had been friends from the time she wrote her first three novels after following the prescribed path — studying English and Creative Writing as she grew up. These first novels were alternately praised for their use of language and the deftness of their characterizations, and damned as being “housewife novels.” She broke through that stereotype with a complex mystery novel called Swann, and suddenly the literary establishment was paying attention.

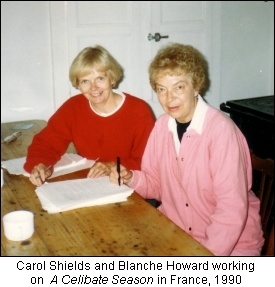

She lived in Winnipeg and I in Vancouver, and on occasions we both travelled and would often spend a day or two visiting. I remember one day we sat on a swing in her yard in Winnipeg and I bemoaned my unpublished fate. She suggested that we co-write a novel about a husband and wife who were separated temporarily by careers that pulled them in two directions and who wrote letters to save money. One of us could write the letters of the husband and the other those of the wife, and so we would have two separate voices around the same theme. She opted to write the husband’s part and even had a name for the novel, A Celibate Season, and so we plunged into unknown territory, mailing our chapters back and forth and reacting to whatever curve the other had thrown.

As we worked at rewriting and editing, on our occasional get-togethers Carol taught me those basics I had missed in my scattered education, how to avoid the use of clichés, the role of metaphor in heightening the drama, the need for small, pithy, readable letters. Eventually we had a novel we were proud of, but it still took us nine tries before we found a publisher willing to take us on. A Celibate Season was published in 1991 and Coteau Books has been well repaid; after Carol won the Pulitzer Prize this small novel sold all over the world and still racks up a few sales each year.

During that time when I thought we weren’t going to place the novel, I wrote a play using it as background. The play won a place in the Canadian National Playwriting competition and was produced here in North Vancouver at the Centennial Theatre.

After that I began yet another novel, this time with techniques I had learned in my apprenticeship with Carol. Penelope’s Way was also published by Coteau and got rave reviews in the Globe and the Toronto Star, among others. It did quite well and is now out as an e-book.

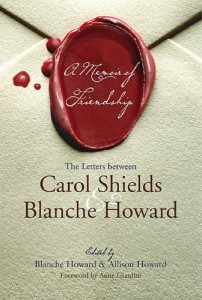

After Carol’s death at the age of 67, her daughter Anne Giardini (also a respected novelist) suggested that I might assemble our copious letters and publish them, and so my daughter Allison Howard and I did just that. Both Carol and I had saved everything — something writers do with a view to becoming famous someday — even the e-mails when these began to replace written letters. We did this for almost thirty-five years. The book, A Memoir of Friendship: The Letters Between Carol Shields and Blanche Howard, was published by Random House in 2009 and got great critical reviews, although mediocre sales.

After Carol’s death at the age of 67, her daughter Anne Giardini (also a respected novelist) suggested that I might assemble our copious letters and publish them, and so my daughter Allison Howard and I did just that. Both Carol and I had saved everything — something writers do with a view to becoming famous someday — even the e-mails when these began to replace written letters. We did this for almost thirty-five years. The book, A Memoir of Friendship: The Letters Between Carol Shields and Blanche Howard, was published by Random House in 2009 and got great critical reviews, although mediocre sales.

Meanwhile my agent had loved one of my earlier novels, and so when e-books hit the world stage she published it in 2010 under her e-publishing imprint, Bev Editions, with the title Dreaming in a Digital World.

§ § §

Since then, Time has crept along on its inexorable path, and my latest novel, finished last year and entitled The Ice Maiden, is up against a fractured publishing industry that has seen the e-world upend all the old rules and send many into bankruptcy. The novel has elicited much praise from publishers — one of the most respected editors in Canada kept it a long time as she tried to decide — but she too ended up saying that they couldn’t publish it in the present fragile publishing climate.

There may well be another reason. I’m not blind to the fact the publishers would think twice about whether a 90-year-old could travel around and promote her book.

But I still have the need to write.

Carol once said to me that if she didn’t write she would become neurotic and that seems to apply to me as well. Perhaps creativity is what keeps our minds steady. All I know is that writing makes me feel that I am doing a necessary thing and not wasting what precious time is left to me. I no longer require permission to write; now it seems that I would need permission not to.

§ § §

If there is writer in the family then we are, by definition, a family that writes. The young in mine seem not to have trouble giving themselves the permission for which I fought so long and hard. My two daughters have written — Allison had her first short story published and Leslie has embarked on a series of novels with an unusual and feisty protagonist. My six grandchildren too dash off things as though there were nothing to it; both grandsons have had a stint at book reviewing and journalism, one granddaughter has ventured into the esoteric world of poetry along with playwriting. All of them have written freely for whatever newsletters or other publications they are involved with.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

I am proud if I broke ground for my family, and perhaps I have pointed out a truth to others. I think all of us, at some time in our lives, wish that we could try something ethereal, whether it is learning to play the piano or writing poetry or painting a landscape, but we block ourselves with all the earth-bound reasons that give us pause: we are making good livings and haven’t the resources to stop; others depend on us and need us more than we need ourselves; we are too old.

It takes courage to overcome the “shoulds” in our lives, but at the end of it I can only say what is true for me: I’m glad I did what I did — and am still doing. Writing.

♦ ♦ ♦

Blanche Howard

Note from Allyson:

Blanche is one of 16 writers who contributed to the collaborative mystery novel At the Edge (Unlimited Editions, 2013). The West Coast launch takes place tomorrow, October 29, 2013, at Vancouver Public Library. Listen to CBC’s Up to Speed interview with At the Edge editors and creators Marjorie Anderson & Deborah Schnitzer.

BLANCHE HOWARD has published four novels, co-authored a fifth with Carol Shields, A Celibate Season, and edited, with her daughter Allison, A Memoir of Friendship: The Letters Between Carol Shields and Blanche Howard. She has also published numerous short stories and essays, mostly in literary journals, including “Dancing with Ray” (Descant, Winter 2009). A full-length play adapted from A Celibate Season was a finalist in the 1989 Canadian National Theatre Playwriting Competition and was produced in Vancouver in 1990. Blanche published Dreaming in a Digital World (2010), an e-novel, and is one of the writers of the experimental novel At the Edge (2013). She recently completed another work of fiction.

What an interesting and inspiring piece! Thank you so much for giving it to us Blanche, and thank you Allyson for publishing it! So many of us need that permission from … of all people … ourselves! (The toughest critic, the loudest nay-sayer!) I know this will give many of us courage.

Thanks, Ally, for publishing that inspiring piece. Congratulations to Blanche Howard, and a big thank you to her for thinking of all of us. Her spirit of encouragement shines through.

Printing this out. It’s worthy of a comfy seat and a cup of tea… can’t wait!

Thanks Allyson. It’s interesting to follow her journey.

Thanks, Allyson – What a great essay by Blanche Howard. It’s inspiring to know some people really hang in and manage to maintain their great ability and sanity for years after others give up. It’s wondering which group you belong to that’s worrying! (I think having a busy life must help.)

I loved Carol Shields’ first three novels, the “housewife novels”! Off now to read A Celibate Season.

My favourite bit was where she said that “…writing makes me feel that I am doing a necessary thing…”. There it is. The question that every writer, at every level I think, needs to wrestle with sometimes. Does the world REALLY need another book, essay, memoir, poem, story, travel piece or revelation on the great white light? Answer: yes!!! Why?? Because ‘that’ version has not yet been done. It’s really as simple as that, isn’t it? And I know it sounds obvious but everything is… obvious. Still, we need constant and regular reminding and those reminders come in all forms. Blanche’s piece was exactly that for me, a wee tap on the shoulder. For which I thank her, and you too, Allyson, for posting.

Thanks for sharing this inspiring piece by Blanche Howard. This essay really resonated with me because until recently I was afraid to not only write what I wanted to write but also to share my fiction/poetry. Blanche is so right, we have to give ourselves permission to write.