“But art is poultice for a burn. It is a privilege to have, somewhere within you, a capacity for making something speak from your own seared experience.”

~ Molly Peacock

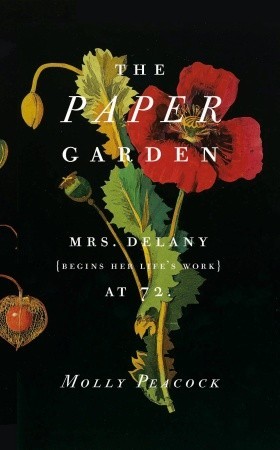

In The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany (Begins Her Life’s Work) at 72, poet Molly Peacock savours the vivid intersections of her creative life and that of eighteenth-century British artist Mary Granville Pendarves Delany. Part memoir, part biography, the book reconstructs Delany’s life from hundreds of letters the woman wrote to her sister in the mid-1700s.

Fascinated with Delany’s artistic legacy — a late-life collection of botanical “mosaicks” titled Flora Delanica — Peacock examines their shared experiences: twice married, the second time romantically to men they’d known in youth, childless, charmed by botanical art, and both thriving artistically in their times. It’s the story of the lives of two women from very different centuries.

Peacock, recognized for unflinching and sensual poetry, seems an unlikely candidate to link intimate poetic modernity to a three-hundred-year-old story of a woman from a minor branch of the British aristocracy. It demands a leap of faith, but one I’m glad I bridged.

By happenstance, in 1986, she viewed Delany’s “mosaicks,” rare, layered paper botanicals on loan from the British Museum to New York City’s Morgan Gallery. The meticulous collages, an art form invented by Delany, captured Peacock’s imagination. Two decades passed before she wrote a biography of the obscure artist, which required an investigation of cultural influences in Delany’s life that led to her exceptional and prolific creativity beginning at age 72.

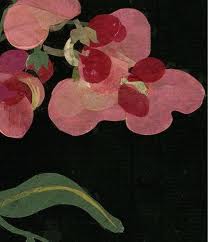

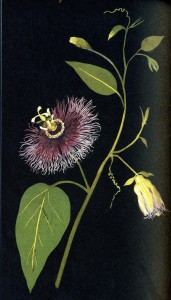

And where does Peacock place herself in this story? What threads connect her to the collages of botanical dots and squiggles layered onto dramatic black backgrounds? Peacock herself had attempted to paint botanicals years before she became acquainted with Delany’s work, and it’s clear she feels awe for the older woman’s persistence and skill. The more she researches Delany’s letters, the stronger grows the bond that transcends time or place.

And where does Peacock place herself in this story? What threads connect her to the collages of botanical dots and squiggles layered onto dramatic black backgrounds? Peacock herself had attempted to paint botanicals years before she became acquainted with Delany’s work, and it’s clear she feels awe for the older woman’s persistence and skill. The more she researches Delany’s letters, the stronger grows the bond that transcends time or place.

“The flowers are like dancers,” she writes. “Like daydreamers. Like women blinking in silent adoration. Like children playing. Like queens reigning or divas belting out their arias. Like courtesans lying on bedclothes. Like girls hanging their heads in shame. Like. Like. Like.”

The Paper Garden is a window through which Peacock allows us to view women’s roles in the eighteenth century and the effects of patriarchy and strict family values. Peacock introduces just enough historical research, political manoeuvring, fashion, philosophy, and hints of lusty gossip to portray a fascinating and sometimes brutal period before the Industrial Revolution and Victorian standards changed the world forever. She exposes the survival modes of an impoverished branch of an aristocratic family, forging connections to the power elite through association, friendship, and marriage. Evident is Peacock’s wonder and respect for Delany’s determined independence, which mirrors her own, but in a century when few safety nets existed beyond social connections.

Peacock teases our curiosity about Delany’s circumstances. She was born in 1700, and had a respectable upbringing. Her family’s Jacobean allegiances, and their hopes for another Stuart King, die with the Acts of Settlement, which require a Protestant ascension to the throne. James Stuart, their choice, is a devout Catholic. The crown passes to Queen Anne’s second cousin who becomes George I. Now the disappointed Delany family must find favour wherever they can.

Delany’s fortunes are entrusted to her powerful, meddling uncle, Lord Landsdown. He forces her into a politically advantageous, but loveless marriage to a titled, selfish, drunken squire (Pendarves). Pendarves is 60 years old, and Mary at 17 is a miserable bird in a gilded cage.

When after nine years the despicable Pendarves dies, leaving his wife with a pitiful inheritance, Mary Granville Pendarves plots for years to gain an appointment to the Georgian court as a lady-in-waiting. During this period she befriends famous composer George Frideric Handel, satirist Jonathan Swift, and painter William Hogarth. Their influences encourage her artistry and solidify her acceptance into widening circles of influence.

Popular coffee houses flourish in eighteenth-century England. Kew Gardens attracts international botanical specimens. Jacobites are thrown into the Tower of London. Captain Cook’s around-the-world voyage is financed by Delany’s acquaintance, the Duchess of Portland. Independent and industrious (but impoverished), Delany develops womanly needlework skills, both as craft and dress design. She plays the spinet, paints, writes, and enjoys the latest pastime of shell-work. Perhaps jaded by one failed marriage, she spurns potential suitors, even the handsome and worldly Lord Baltimore. She writes hundreds of letters to a beloved sister and pursues gardening as a serious hobby. Her acute powers of observation develop into devotion to detail.

In midlife, the self-sufficient widow reacquaints with a male friend from her youth, Patrick Delany. She falls in love with this Irish cleric of modest means and marries for a second time. They relocate to the Irish countryside, where the seeds for her happy, unexpected legacy are planted in fertile soil.

They had been married twenty-three years when Patrick dies, and Delany moves in with the Duchess of Portland, a wealthy sponsor of Kew Gardens and an enthusiastic collector of plant specimens. Delany’s story might never have been told had it not been for the fact that in her early seventies, the widow picks up her scissors, tweezers, and a scalpel, and creates an unusual floral culmination of her life’s work by pasting thousands of pieces of coloured paper to black backgrounds. She often made her own paper, dying it in the hues found in nature.

They had been married twenty-three years when Patrick dies, and Delany moves in with the Duchess of Portland, a wealthy sponsor of Kew Gardens and an enthusiastic collector of plant specimens. Delany’s story might never have been told had it not been for the fact that in her early seventies, the widow picks up her scissors, tweezers, and a scalpel, and creates an unusual floral culmination of her life’s work by pasting thousands of pieces of coloured paper to black backgrounds. She often made her own paper, dying it in the hues found in nature.

What in Mary Delany’s long life of disappointments, hard work, and happy second chances does Molly Peacock find to relate to? In her words:

“But art is poultice for a burn. It is a privilege to have, somewhere within you, a capacity for making something speak from your own seared experience.

“A multitude of vectors brings us to the moment where we are, and where we love, or cough, or say the wrong thing, or fail, or feel our fate in what we fear, or to a moment where clarity descends, and we understand the world simply from having observed it. Uncontrollable events hurtle toward us until the very moment of our deaths, yet in each instance figuring out how to go on, even on to the next world, repeats the confusion of youth. Of course we need our role models long past adolescence.”

One of the tributes Peacock pays Delany is the choice of book jacket, cover art, and paper stock: thick, glossy pages showcase the “mosaicks.” Every chapter begins with a full-page reproduction of one of Delany’s flowers. I couldn’t resist placing a magnifying glass over them, knowing that some of the flower heads comprise more than two hundred pieces of paper, the lines blurred by the artist’s exquisite skill. Delany sometimes pasted original dried and pressed leaves and petals to create the overall affect, a technique known today as mixed-media collage.

Molly Peacock’s skilled storytelling, her pen a paintbrush, brings Mary Delany’s lively experiences into this century. Deftly weaving their two stories, the author reveals somber lessons, reminders of our vulnerability to the challenges that arise with a long life, our shared fears, the transcendence of our triumphs, the measure of what we make of our talents, how we learn from others, our connectedness, our humanity.

♦ ♦ ♦

The Paper Garden: Mrs. Delany (Begins Her Life’s Work) At 72 was published by McClelland & Stewart Ltd. in 2010.

MARY E. McINTYRE is a writer living in Stouffville, Ontario. She blogs at Washburn Island: Memoir of a Childhood and Camera Combo.

Lovely review, Mary. Mrs. Delany shows us it’s never too late to realize our creative potential.

Mary … you are gifted! Fabulous review.

As gracefully as Mollly Peacock writes about Mary Delany, so does Mary McIntyre write about both women. Mary’s review illustrates her own talent in memoir and love of flora. All three dance on the page!

Dear Mary McIntyre,

It was a privilege to read your thorough, lively, astute review!

Best wishes,

Molly Peacock