This is Part 1 of a 2-part interview.

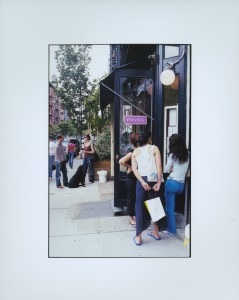

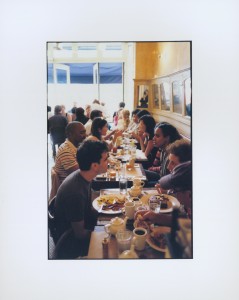

GABRIELLE HAMILTON is the chef/owner of PRUNE, which she opened in New York City’s East Village in October 1999. PRUNE has been recognized in all major press, both nationally and internationally, and is regularly cited in the top 100 lists of all major food magazines. Gabrielle has made numerous television appearances including segments with Martha Stewart, Mark Bittman, and Mike Colameco and most notably was the victor in her Iron Chef America battle against Bobby Flay on The Food Network in 2008. Gabrielle has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, GQ, Bon Appetit, Saveur, and Food & Wine and had the eight-week Chef’s Column in The New York Times. Her work has been anthologized in Best Food Writing 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2011. Gabrielle was also nominated for Best Chef NYC in 2009 and 2010 by the James Beard Foundation and in 2011 won the category. She is the author of the New York Times bestseller Blood, Bones & Butter: The Inadvertent Education of a Reluctant Chef, which has been published in six languages and won the James Beard Foundation’s award for Writing and Literature in 2012. She lives in Manhattan with her two sons.

My students and I welcomed Gabrielle as guest author for a session of my online course Memories into Story: Life Writing (University of Toronto, SCS). What follows is an edited version of the class’s collaborative interview about her memoir and the writing life.

“This has remained with me forever, the necessity of a varied rhythm to the sentences on a page, long strokes interpolated with short jabs, the power and energy of rat-a-tat-tat sentences and the leisure of long, fluid ones, and when and how to use each.”

We remember life in “scenes” — like beads on a necklace. But we often have difficulty seeing the narrative arc in our own lives, especially when events are recent. Did you face this difficulty in writing Blood, Bones & Butter? What’s the remedy — besides waiting twenty years to discern that arc?

I found the very act of writing it all down helped me tremendously not only in organizing the narrative arc of my book but in understanding the narrative arc of my own life. Those “scenes” add up to something. And I think it’s possible to determine what they add up to, depending on how you choose to string them. I was stunned regularly at the realization that I could have written this book, could have organized this arc, could even have understood my own life, really, in at least six different ways. You don’t put every bead on the necklace. And you decide if you want an eighteen-incher or a choker or a knee-length flapper string — all necklaces, all with beads — all needing very different structures depending on what you decide.

I found the very act of writing it all down helped me tremendously not only in organizing the narrative arc of my book but in understanding the narrative arc of my own life. Those “scenes” add up to something. And I think it’s possible to determine what they add up to, depending on how you choose to string them. I was stunned regularly at the realization that I could have written this book, could have organized this arc, could even have understood my own life, really, in at least six different ways. You don’t put every bead on the necklace. And you decide if you want an eighteen-incher or a choker or a knee-length flapper string — all necklaces, all with beads — all needing very different structures depending on what you decide.

The rules I gave myself for this particular telling of the story were that it had to have food throughout — because I’d been given a book contract for the fact of my being a chef, and for whatever reasons, chefs and food are a hot topic these days. And people could only appear in the pages inasmuch as they pertained to the food being written about. Many people who appear in my book disappear as soon as their “scene” is dispensed with.

I found it helpful, at certain points, to do that physical thing where you print out and colour-code the scenes according to their themes and hang them up on the walls and study the pattern and arrhythmia of their trajectory around the room of your apartment. Does it make sense that a dark blue scene is making its appearance all the way over here in the section of bright red scenes? It certainly may. Or it may not, but you are prodded to discover the answers by the simple visual cue of colour. Equally, it was helpful to notice a saturation of certain colours and to notice the scarcity of others. Then you have to discover what there is to discover — both technically and in the emotional arc — about that excess or that scarcity of certain scenes. What is it you are avoiding, or what is it that you are just so damned comfortable repeating yourself about? I found this illuminating both in life and in the structuring of the memoir.

I agree mostly that what is near and recent is the most difficult to see well, understand, and consequently to structure. There are times when it’s crystal clear, though, too. When I was writing BBB, it was proving very difficult for me to end the book — and I am aware that the ending is not that satisfying in that it leaves many questions — because I still did not know at that time what the full meaning of my marriage was and I certainly did not know what the outcome of my marriage would be. I lacked the rear-view mirror perspective and it shows in the writing as a weakness, I acknowledge. But you do your absolute best and bring whatever truth you do know to the job in front of you.

You have the ability to describe settings rich in detail. I’m sure you are a naturally observant person, but I’m wondering how you cultivated those skills over the years. For example, in “The Lamb Roast” did you have to go back and ask your siblings for their recollections of the time and places you are writing about? Were some of them “re-imagined” — taking literary licence but in keeping with the emotional truth of your memories?

I asked my siblings for their recollections, I looked at photographs, I kept journals even as a kid, I went back to my hometown frequently and retraced many footsteps, and I “crafted” the story with all the appropriate tools for the job. As you so rightly point out, it is a memoir, which takes literary licence — not a piece of journalism. After the book was published I learned that Gunther from the Ringling Brothers circus was a tiger tamer not a lion tamer! Even the copy editor missed that!

Which course — or professor — from your MFA experience most influenced your writing and why? Or were there other influences?

The MFA program was not at all about that for me. I kind of just hung out and got some rest in the writing program there. It was more of a sabbatical from my intense work life than an influence on my writing, and an especially restful one because I was working in this particular industry, which someone once described perfectly by observing: it’s the only job in which you work hard all day long to get ready to work hard all night long. The MFA program was a luxurious opportunity to get back to reading — you read a great deal in grad school — and reading is the only way to good writing, that I’ve ever experienced, at any rate.My writing was most significantly influenced much earlier on — in high school — by Peter Brodie, the English Lit and Latin teacher I had for three or four years straight, who had us — at fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old — reading all kinds of shit that should have been out of our grasp: Shakespeare, Boswell, Johnson, Chaucer, Brontë, Austen, Durrell, Maugham, even the Bible sometimes for its lively storytelling and also its sentence structure. That man loved the emphasis of a sentence that started with the word And. And he delighted in pointing out that all grammarians everywhere argue against it. It’s possible his most cherished book of all time was The Life of Samuel Johnson by James Boswell, which is now one of my favourites, too, for its mightily intelligent, rational, and succinct wit. Johnson was just exceptionally quotable.

Brodie pulled the books apart, line by line, showing us how some of the best sentences were: All cow; no bull. Or, conversely, how clever and masterfully oblique some could be. He showed us the energy of an active sentence — subject–verb–object. The deadliness of a passive sentence — adverb–adjective–adjective–adjective–intransitive — zzzzz. He made us read our writing aloud to discover where it was cluttered or clunky or improperly punctuated. If you yourself were literally tripping over it in certain places, or losing your place, or your energy, or your point, the reader certainly was also. He collected our own copies of each assigned book each week and if we hadn’t torn that book up with pencil notes in the margins, underlinings, and question marks next to unknown vocabulary words he lowered our grade. He railed against the use of a $20 word when there was a lovely, efficient, and sturdy word right in front of you that would get the job done better. But he was hardly against big words, beautiful words, onomatopoeic words; indeed, he was passionate about words. He was not suggesting ever that we shouldn’t know deeply the meanings of the $20 words and have them in our grasp, but he just insisted that they be used correctly and not sloppily, like most of us at sixteen years old were apt to do in an attempt to inflate our papers or to make ourselves sound more intelligent or to make our sentences seem more “arty” — he couldn’t tolerate it.

Brodie LOVED a healthy, virile, two-word sentence perfectly placed at the end of a series of long, compound ones. And he laughed out loud for actual minutes in the classroom, delighted when he came upon a good one. This has remained with me forever, the necessity of a varied rhythm to the sentences on a page, long strokes interpolated with short jabs, the power and energy of rat-a-tat-tat sentences and the leisure of long, fluid ones, and when and how to use each.

I want to emphasize that he was not our writing teacher; we wrote a great deal in his classes of course and he shepherded our papers into their best versions, with rigorous standards, but he was teaching literature classes. Guiding us to good reading. And examining what made the work we were reading so successful, enduring, eternal, and canonized. Needless to say he was adamantly — and articulately — not a proponent of opening up the canon to nontraditional voices! He felt that everything, absolutely everything important about the human condition that needed to be said had already been said best by the Greeks, or at least in the one hundred greatest books of western civilization, and that their wisdoms spoke to universal humankind. I wonder what he would make of the impeccable Junot Diaz? He made us use a Roget’s Thesaurus and The Chicago Manual of Style, and Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, and most influential of all, from him I learned to use an Oxford English Dictionary, which at the time was seventeen volumes long and has since grown to twenty volumes. I still own — have lugged with me from state to state, apartment to apartment, decade to decade — the same abridged two-volume edition with the magnifying glass that I bought in high school and I use it almost daily. Even my nine-year-old, fourth-grader son is now hooked on the thing. I think everyone should have one.

When you write something as magnificent and gutsy and as close to the bone (sorry) as Blood, Bones & Butter, how do you cope with critical reviews?

There is not a single thing anyone could have said about my work that could possibly have been more self-savaging than what I had already said to myself hundreds and thousands of times during the writing. I am a real monster, a viciously unkind reader of my own work. It’s paralyzing. And I am not proud of it. What I have figured out to do for the time being is to attend to the content of my own vituperative lashings, to go back to the writing and see what I can do to address the harsh criticisms, and to make the writing answer to the assaults being levelled at it. By the time the book hit the market I had already taken myself down as brutally as one can, and I had diligently brought my bloodied self back to the pages and answered all of the imagined criticisms to the utter best of my abilities; I did not phone in a single sentence of this manuscript. That does not mean the work is not flawed, that the book is not weak in spots; but the worst — and truest — thing a reviewer could have said is that I just don’t have the talent, and I had already grappled with the limits of my talent and acknowledged them to myself. And the worst things a general reader could have said — that I am sometimes ugly, stupid, boring, self-aggrandizing, falsely modest, cruel, contradictory, sexually complicated, ambivalent, angry, injured, and narrow, I had already acknowledged to myself, but also I somehow understood that that is what it actually is to be a fully emancipated human — which I couldn’t imagine being hurt by if someone wanted to criticize me for it.

You have an amazing way with words and I found many of your descriptions brought me right into your story, often laughing. Are there some aspects of writing that flow easily for you and others that you have a harder time with? How do you overcome this?

The initial throw-up onto the page is easy. The disciplined edit, rewrite, edit, rip, stitch back together is the doozy. See my earlier answer about self-savaging and then facing the savagery diligently until you can reasonably stand up for the work.

What was your biggest challenge in writing your memoir?

The biggest challenge was admitting I was writing a memoir, which galled me so terribly in the beginning because I have been taught, like everyone who’s ever taken an English class in their life or read the New York Review of Books, that memoir is what women write, that memoir is confessional, that memoir is soft and silly, that memoir is where lesser writers air old gripes and settle scores, and that real literature is only a novel, written by a man or a woman pretending to be a man. Once I admitted to myself that I was not as good as I wished I was, that I was not as manly and as literary as I would have liked to be — once I had that frank and painful conversation with myself about the extent of my current talents — I got on with it and wrote the best memoir I could, making it as “literate” and novel-like as I was able by facing those harsh put-downs of the genre itself and answering to them.

You write passionately about people in your life. Were the earlier relationships easier to write about because of the distance in time or the more current ones because they may be more fresh?

I think people and relationships are the hardest thing to write about — ancient or fresh. It’s imperative to try to understand what you are observing: what is that person doing? And why is he doing it? Which is important to know and understand about yourself, too, in relation to your subjects when you are trying to write about them. What am I doing writing about these people and why am I doing it in this way?

While reading excerpts of your memoir, I felt like I was being let in on secret family conflicts. In writing openly about family members, do you want the reader to take sides? I would be afraid of my inner demon escaping. I would want to expose how horrid others had been to poor me! Is that a temptation? Were your earlier drafts harsher or gentler than the final manuscript?

While I am often struck by the truly obscene unkindness of what people allow themselves to say and do to each other within the privacy of their intimacies — between husbands and wives, parents and children, lovers — I, like you, have been raised with exactly the same understanding of the sacredness of safeguarding that privacy. Do not let the inner demon escape! And I, like you, have been raised with exactly the same attitudes about who you would have to be to even let yourself describe, let alone reveal, the despicable and demeaning shit we say and do to each other within that special privacy of marriage and family, which, if I understand your tone correctly amounts to: you are a self-pitying, overdramatic pussy who can only muster in your puny imagination a simplistic two-dimensional narrative of “look how horrid others have been to poor me!”

So no, I was not tempted to let anyone in on the secrets, to break the sacrosanct rules of the privacy of intimacy, or to allow myself to be such a self-pitying pussy with such a puny imagination about the reciprocal complexity of humans and relationships, because I fully understand how transgressive and unattractive that would be. Not to mention what a boring read it would make. What’s on the page, in BBB, is the stuff that we all agreed was up for grabs, available for public consumption, and that was fully vetted beforehand by everybody who appears in the book — my mom, dad, siblings, husband, Italian family, employees, grad school colleagues, etc. I was asked to not include a few things from the original drafts and I happily obliged.

Once upon a time I owned a restaurant, and your stories about your days there rang true down to my nerve-racked bones. I felt a pace in the writing about those days that was different, wonderfully so, fast, and frenetic, and then as your relationship developed and your family life expanded the flow of the writing changed. If I’m even right, was this intentional on your part?

I hope everything I said above about my teacher Peter Brodie in high school answers this question! Yes. Every single word was intentional, the lengths of sentences were intentional, the varying fluidity, lyricism, and wordiness of sentences was used on purpose as was the employment of staccato, terse, and muscular sentences. Different tools for different jobs. Still, I am aware of how much of a beginner I am! Someday I want to hold the reins of that team of horses with impeccable slack-tense form.

I am amazed at how you have so successfully managed not only to own and operate a successful restaurant in a competitive market but to do so while raising children … AND write, again successfully. How do you arrange the time for yourself to focus on writing?

It was a particularly gruesome period, and we all got hurt — my restaurant, my kids, and not least of all myself. I wrote while standing on the line in my apron between dinner pushes — often with a Sharpie on a piece of torn brown butcher paper that we use to set the tables in the dining room. I wrote while nursing in the middle of the night, with a sleeping infant on either side of me and an Itty Bitty Book Light clamped to my notebook. I did not sleep more than four hours a night for some four years, and sometimes not all of those hours were consecutive. Needless to say, I was ragged, shrill, and profoundly out of whack. I would never have done it that way if I’d known a different path. But each thing in front of me was non-negotiable: my children, my restaurant, and my book contract. I had already been given the money! I believe this insane scenario describes the lives of a billion women, rich and poor, across cultures — we just have so much non-negotiable shit to do and we just do it, somehow. I will say, though, that I personally have never figured out how to make writing a non-negotiable practice if it isn’t attached to a contract and a deadline.

What particular challenges are inherent in food writing?

I notice a couple of challenges in writing about food and they both have to do with improperly estimating its density. Sometimes the poor little category ends up being a place where writers with big ambitions try to load up their little story about lasagne with this giant freight of meaning, and they load up that poor lasagne pan with so much more than it can possibly convey. Or conversely, food writing as a category — because of its hyphenation and because of food feeling like a universally accessible topic (we all eat!) — is not treated with as much rigour and care as it deserves, but it is still writing after all. Food writing is challenging to get “just right” in terms of gravitas, and is generally overtaxed or underestimated.

Read Part 2.

I read BBB when it first came out a couple of years ago. It is an excellent book in both craft and content, which I recommend regularly. This is a terrific interview (great questions, class). No wonder BBB is so well written, with Hamilton’s focused intention and supremely high expectations. It makes me want to eat at her NY restaurant Prune more than ever… I know it will be a great meal. Bravo to writer and interviewer(s).