My secret life is not to be confused with a “secret identity.” I won’t be dashing off to a phone booth and emerging in a Superman costume.

I don’t have a secret identity. But I do have a secret life, and it is inextricably tied in with my identity as a writer.

This secret life — the one that doesn’t involve changing into Superman in a phone booth — began when I was a child. I think a great deal of a writer’s path is formed in childhood, when we so much enjoy make-believe, hiding, becoming something or someone else. All children enjoy that sort of thing, but it appears that writers don’t want it to end.

My secret life became serious when I was about 11 years old. I used to share a bedroom with my two brothers, so you can imagine there wasn’t much privacy, but there was a fair amount of teasing. I participated in games and the usual roughhousing that goes on between boys, but what I most enjoyed was reading, especially on a rainy day. And if my brothers were being too raucous, I would retreat under my bed, with my book and a flashlight and sometimes the smaller of our two dogs, the one with a cozy disposition.

Around this time, I bought a diary. I’m not sure why. Probably because of the look of the thing. It was one of those fake leather-bound affairs with a worn cover that was supposed to make it look old. Something an explorer or sea captain might have. I didn’t have much to record since I hadn’t done any travelling to exotic lands or have a knowledge of buried treasure. There was the weather, of course. But it was sunny most of the year. There were the scores of my favourite soccer team, maybe the description of a movie I’d liked. Not too many secrets though.

Until I fell in love with Susie Cooper. She went to a girls’ school and I went to a boys’ school, but we waited at the same bus stop. She was beautiful, naturally. And I wrote that down in my diary. Along with what she was wearing, or if she’d looked in my direction. Sometimes I wrote our names, as if we were married. Susie DeSoto. Or Lewis Cooper.

Susie had no idea I was in love with her. No one did. And I would have died of embarrassment had my infatuation become known. Especially by my brothers. But my diary knew. That was where I wrote that she was wearing a red sweater, and that when she laughed her voice sounded like water running over pebbles. Imagine the consequences if my brothers had seen that last phrase. They would have teased me relentlessly, and told their friends, and maybe passed my diary around at school and the news might even have gotten back to Susie Cooper and she would think I was the biggest twit in the world and would probably take a different route to school and I would never see her again.

So I wrote in code. My first secret. Well, my second actually, if we count falling for Susie Cooper as the first. I didn’t actually devise the code myself. When I wasn’t busy being in love with Susie Cooper, I was reading stories about spies and invisible ink and clandestine radios and coded messages written on the back of postage stamps. I got the code from something called The Big Book of Spy Stuff. I suppose anybody could have looked through it and found the key to my code and deciphered my diary, but luckily no one else in the family was interested in spies.

So I wrote in code. My first secret. Well, my second actually, if we count falling for Susie Cooper as the first. I didn’t actually devise the code myself. When I wasn’t busy being in love with Susie Cooper, I was reading stories about spies and invisible ink and clandestine radios and coded messages written on the back of postage stamps. I got the code from something called The Big Book of Spy Stuff. I suppose anybody could have looked through it and found the key to my code and deciphered my diary, but luckily no one else in the family was interested in spies.

The code was a fairly elementary one, something along the lines of assigning a number to each letter of the alphabet, and was probably best suited for brief messages, and not the tedious procedure of transcribing the gushings of a schoolboy crush. But Susie was worth the effort.

I kept the diary on my little bookshelf next to my bed, and when I wasn’t home I liked to think of it there, containing my secret thoughts, and my feelings. It made them real and worthwhile, because they were in a book, and wholly my own.

Later, when I no longer lived with my snooping brothers, I dispensed with the code. But by then the diary was a journal, and it was a way to think about the world. I still wrote things about whatever girl I was mooning over, but I also wrote down dreams, impressions of people, what I was feeling, and even sometimes little ideas for stories.

I came to realize that I had a secret life. The life of the mind, or the imagination, or the emotions — call it what you will. There was the me that was public, with my family or friends or at school, and there was the me that was not discussed with anyone, that was personal, hidden in a book that only I read. This gave me freedom. I could write anything down.

Now, of course, I want people to read my ramblings.

But those journals were my secret life. And in a way, they were also my real life, because there I could be most myself.

At some point I stopped writing journals and started writing fiction. I don’t go back and read the diaries and journals. I’m embarrassed by my own naiveté and pretentiousness. I’ll get back to this notion of being embarrassed in a minute.

But I do want to say that the writing of private diaries and journals is a good practice for aspiring writers. You get used to seeing your thoughts on paper, you get used to thinking on paper, and you get used to confessing.

Which brings me to the second part of my title, “A writer confesses.” I’m not going to tell you that I stole from the cookie jar or didn’t pay my taxes or that I do actually have a Superman costume under my shirt. I want to talk about when the writer confesses — and it is just as difficult and revealing as being on the witness stand in a courtroom, or in the priest’s confessional, or on the therapist’s couch. Publishing a book is all of that.

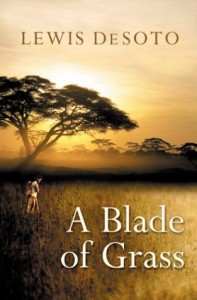

When I saw my first novel, A Blade of Grass, in a pile on the table at Indigo books, the first thing I felt was not elation. Which is what you might expect a first-time novelist to feel. After all, isn’t the whole point of all that work to see your name on a book cover in a store?

When I saw my first novel, A Blade of Grass, in a pile on the table at Indigo books, the first thing I felt was not elation. Which is what you might expect a first-time novelist to feel. After all, isn’t the whole point of all that work to see your name on a book cover in a store?

But what I felt was a kind of terror. I realized that my secret life was now public property. Anybody could now peer at my thoughts and feelings. And discuss them. I was exposed.

Writing is one of the most solitary occupations. It’s very private and insular. The closest thing I can think of is being asleep and dreaming. The weirdest and most embarrassing things can happen in your mind. Anything goes. But once your solitary, private thoughts are committed to paper, and published, anyone can look at them and talk about them and ask you about them. In your dreams you will find shame, anger, sex, violence. These are some of the things that we don’t usually talk about, except maybe to the priest or the therapist. But the writer makes them public. Or ought to.

For without those thoughts, how can you make interesting fiction? It is only by going to the depths of the soul, to investigate any and every feeling or fear or desire, that you can find truths. The best fiction is honest. The worst fiction tells obvious lies. We say it wasn’t convincing, or it didn’t seem true to life, and we just plain refuse to believe anybody would do such and such.

So you see the writer’s dilemma. She doesn’t want people to think that behind her pleasant facade is a dark heart. But how to understand the heart without at least thinking some dark thoughts and writing them down.

And then people ask you, Is the book based on your own experiences? and you think back to that passage where the boy soils his pants, or the woman inflicts violence on her family, or the man wants to commit suicide, and then you want to say, Nope, I made all that stuff up. People nod, but they give you that look that says, Mmm, you’ve got some troubling thoughts. They look at the photo on your book jacket and think, Good book, but there is something odd about his eyes. Or, you write a fantastic love story and everyone thinks you’re a Casanova, or you’re looking for love.

This notion of confession first came to me when I published A Blade of Grass. The story is mostly about two women, and it’s told from their points of view. When I did readings I was often asked the same question — Why did you write from a woman’s point of view?

There were a number of answers. First, and obviously, the book is about the women’s experiences. But I had wanted a fresh narrative, something that would challenge me to think twice every time the characters reacted to something. I didn’t want to rely on my usual assumptions, or on my own psychology. To put myself in another’s shoes was a challenge, which I believed would make a richer novel.

The solution? Create a surrogate. Create an actor that is you, but not you. Then you are free to be yourself. That sounds paradoxical of course. But it is true. In his plays, Shakespeare has jealous liars, lovesick teenagers, homicidal wives, and a man with a donkey’s head. It’s all the same writer, the same person. But let your actor be responsible. I confessed through the two characters, or actors, in A Blade of Grass.

The solution? Create a surrogate. Create an actor that is you, but not you. Then you are free to be yourself. That sounds paradoxical of course. But it is true. In his plays, Shakespeare has jealous liars, lovesick teenagers, homicidal wives, and a man with a donkey’s head. It’s all the same writer, the same person. But let your actor be responsible. I confessed through the two characters, or actors, in A Blade of Grass.

I’m not suggesting that the writer does this to make literary occasions easier, or so that she can dodge difficult questions. No one else wrote the book, of course, but you. So you are responsible for what the characters do. The point is to stop the inner censor from telling you what you shouldn’t write.

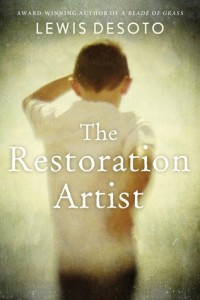

There are some things in my new book, The Restoration Artist, that were difficult to write because they were confessional. But at this point I feel confident enough as a writer to not have to hide behind a character. And I no longer fear being caught naked in public. Yes, it’s all me, but it’s also all fiction.

It’s all true, except the parts I made up.

§

“My Secret Life: A Writer Confesses” is based on Lewis’s speech of the same title for the 2013 Ontario Writers’ Conference, held in May in Ajax, Ontario. Lewis kindly permitted me to publish it here. I had the pleasure of working as freelance editor on both his novels.

♦ ♦ ♦

LEWIS DeSOTO was born in South Africa and moved to Canada as a teenager. His first novel, A Blade of Grass, was an international bestseller and an International Book of the Month selection. Longlisted for both the Man Booker Prize and the Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger, the novel was also a finalist for the Royal Society of Literature Ondaatje Prize and the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing. An artist as well as a writer, DeSoto authored a biography of the painter Emily Carr. He lives with his wife, the artist Gunilla Josephson, in Toronto and Normandy, France. Visit him online at www.lewisdesoto.com.

What a lovely way to put into words the process of becoming confident with the ‘growing up’ of thoughts, emotions and ideas.

What a beautiful essay and story. I think I’ll start reading fiction again. Thank you both for inspiring. xx