Something a little different this week for Wordless Wednesday — a family-history related set of photos. I’ll explain more in the Comments.

(Click photos to enlarge.)

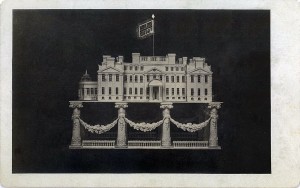

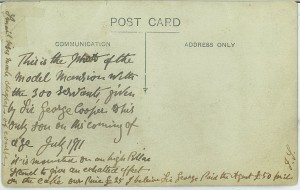

Postcard text: This is the photo of the model mansion with the 300 servants, given by Sir George Cooper to his only son on his coming of age July 1911. It is mounted on a high pillar stand to give an exhalted effect on the cake. Our price £25. I beleive [sic] Sir George paid the agent £50 for it. J.S. [Joseph Sleap] Up the left side: Small sizes made cheaper of course.

Hursley Park, Hursley, Hampshire. (Photo: H. Bedford Lemere, 1905. English Heritage, NMR. Reference number: BL18761A)

Scroll through more of my photos here.

And check out these Wordless Wednesday contributions from some of my (not typically wordless) writer friends.

Elizabeth Yeoman (Wunderkamera) will return soon

Recent posts on writing

Will Come the Words: Kristen den Hartog’s creative space

Make the Judges Care: How to up your odds in a writing contest, guest post by Anne Mahon

Seven Treasures: On stuff that “digs in,” guest post by author Alice Kuipers

Interview with NYC restaurateur and memoirist Gabrielle Hamilton (Parts 1 and 2)

Memoir as Survival: On writing Lorenzo’s Heart, guest post by Jennifer Massoni Pardini

Vanishing Letters of War: What we stand to lose, essay by Allison Howard

Enquiring minds want to know more! (I’m currently stuck on the 300 servants… could one of them come and ‘do’ my house?)

Burning curiosity aside, I suppose we *are* meant to imagine the possibilities. In which case I wonder if the lad liked the cake as much as his dad enjoyed having it made. Twenty-five pounds would have been a small fortune then, and fifty… well. Cheaper than giving him the house. (Was it Cooper’s house? In which case was the deed enclosed with his birthday card?? (: Because if it wasn’t, I’m wondering at the significance of this gesture. And I can easily see the kid saying if it’s just a fancy cake, he’d rather have the twenty-five pounds.) Much potential here for hmmmmm. Which is my favourite part of the game.

Love this, Allyson. Looking forward to the WHOLE story. Or as much of it as you know. Am thinking you found the postcard somewhere and maybe it’s as much a mystery to you…

Allyson, Ms. M has posed most of my questions above — but ALSO I want to know whether when you say “family history” this intriguing tale in fact involves, somehow or other, YOUR family — either as mansion owners or bakers or postcard makers? Do tell! Most intriguing, thanks for the nifty almost wordless puzzle.

All the above questions, Allyson, and also – do you collect old postcards?

Very cool cake, err um, model mansion … oh, wait – Hursley Park! Looking forward to hearing more about the family-history, Allyson.

hi Allyson,

How did you discover it was Hursley Park? You’re detective skills are amazing,

Love, Paige

I loved all your guesses and questions. Here’s the story:

I’m related to Joseph Sleap, the ornamental confectioner of North London who designed the sugar-art cake-topper (photo 1) and wrote the postcard (photo 2). He was my great-great-grandfather on my mom’s side. My great-grandmother Rosaline, Joseph’s daughter, appeared as a young woman on censuses as confectioner’s assistant. There were confectioners in at least two previous generations of the Sleap family as well.

My aunt had the postcard (along with another picture of one of Joseph’s sugar cake-toppers) and I saw it for the first time this summer when we visited her out east. My husband was the one who discovered, by Googling “Sir George Cooper,” that the confection was modelled on the estate called Hursley House (or Park) in Hampstead. It’s now IBM Headquarters. There’s a whole modern complex attached to it, but the original house is still the company’s executive briefing centre.

By the way, Hursley estate dates back to at least Richard Cromwell’s time. There’s a light-hearted history of it here: http://www.hursley.hampshire.org.uk/history_of_hursley.htm

And I found an interesting article on “The Art of Confectionery” by food historian Ivan Day, in which he writes,

“In the eighteenth century, the confectioner was the most highly regarded of all tradesmen involved in the preparation of food. His skills were considered to be of a more elevated order than those of a mere cook or baker and if he was successful in his craft he could command not only impressive financial rewards, but a respectable social standing usually denied to other food professionals. Some confectioners found employment in the households of the aristocracy. Others ran their own shops in the cities and large towns and sold a remarkable variety of sweetmeats, biscuits and ices, as well as the elaborate table furnishings necessary for the lavish entertainments of the rococo age….”