Tilya Gallay Helfield launched her story collection, Metaphors for Love, last night at Holy Blossom Cultural Centre’s new Salon Series. She was a participant in several of my workshops over the years, both online (Ryerson University, Days Road Writers’ Workshops) and classroom (Koffler Centre of the Arts). I also worked with her as editor on early drafts of the stories appearing in this collection.

Metaphors for Love (Imago Press, Arizona, 2015) comprises twenty linked semi-autobiographical stories. They begin during the Second World War, when Ruth, the protagonist, is living in Ottawa, Canada, but the tales move back and forth in time over a period of six decades, exploring the lives of her eccentric grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, and siblings. These stories are by turns dramatic, heartbreaking, humorous, and poignant, with spectres of death and war honing some to an unexpectedly sharp edge. Metaphors for Love is available through Amazon.ca in paperback and on Kindle, or it can be ordered from the author at thelfield@rogers.com (free delivery to some addresses in the Toronto area).

“I desperately wanted these stories to be heard, and I was the only one who could write them.” ~ Tilya Gallay Helfield

Tilya, how long have you been writing your stories in a focused way?

I first started telling the stories in Metaphors for Love to my children more than fifty years ago. Later, at their urging, I began to write them down. I can’t remember when I began writing “Blink,” the first story in what ultimately became this collection. I’d been writing since I was a teenager — essays, poems, a satirical version of “Alice in Wonderland” set in outer space. I had a few publications here and there — a poem in The Northern Review, a humorous piece in TV Guide, a series of articles on Asian Jews in Viewpoints. For several years, I wrote a humour column for two Montreal weekly newspapers. I think I started “Blink” about forty years ago, around 1975. “Nylon Stockings” was the first of the stories in this collection to be published, in The Fiddlehead in 1997, more than twenty years later.

And then the stories that I was writing for this collection started to be published — ten stories between 1997 and 2014. Things were looking up.

My book, however, was rejected by nine publishers before the tenth one accepted it. Maybe the secret to writing success isn’t talent, after all. Perhaps it’s just hanging in there until everyone else gives up and goes home.

Were there times when your commitment flagged? How did you keep yourself writing?

I don’t think my commitment ever really flagged, at least not for very long. Sometimes I hit a wall and things didn’t go well. But I was lucky. I had my painting to fall back on. So I’d concentrate on painting for a while to clear my head and then go back to my writing with a renewed and refreshed point of view, ready to give it another go.

I was certainly interrupted, though. Constantly. A husband and four children take up a lot of time and energy. So does a spinal fusion and several other orthopedic procedures, plus various illnesses. But before and after and sometimes even during these episodes, I kept writing. I would struggle with something all day and just begin to get somewhere, when I’d have to stop to take the girls to ballet or my son to hockey practice or get supper for my husband. I carried a notebook with me so I wouldn’t forget my ideas before I could get back to my typewriter.

I had no personal social life, by choice. I never went out for lunch with friends. When we went away for the weekend, I took my laptop with me and wrote. My husband was a busy attorney and a city councillor, with all the attendant social demands on my time. And there are school functions, playdates, bar mitzvahs, weddings, the births of grandchildren. I will be a first-time great-grandmother in June. Through it all, I just kept writing.

I never had a room of my own in which to write. So I did my writing on my dining room table, when I’d cleared the dishes away after every meal. I wrote and rewrote each story more than a dozen times, after sending it out and being denied publication. I would put it aside and start another story, with the same result. My poor postman took it very hard, commiserating with me each time he brought me a rejected manuscript and telling me he hoped I’d have better luck next time.

I never had to do anything to keep myself writing. It was just some inner urge that I had to satisfy. I could only relax at the end of the day when I had put in a good writing session. I still feel guilty on a day when I haven’t written (or painted). Just as I can’t go to sleep at night until I’ve brushed my teeth and done my exercises. I desperately wanted these stories to be heard, and I was the only one who could write them.

How did this structure evolve? Did you ever consider other structures?

I had the structure of a series of linked short stories in mind when I first began to write this book. It was a natural — the early stories dealt with a specific family living in a small neighbourhood in a Jewish community in Ottawa, and all the stories dealt with what happened to several members and generations of that family as the years passed. At one point, an editor convinced me to try to make the stories into a novel. I spent more than a year doing this, but I was very unhappy with the result and finally reverted to my original plan.

To what does the title refer?

The title refers to something someone once said — that when families fall out, it’s usually about money, but money is just a metaphor for love. In Ruth’s family, there was attention paid to money — the spending, or rather lack of spending, during the Depression, followed by six long years of war. But there are other metaphors for love in these stories — an inheritance, a bicycle, an altered dress, a jar of pickles, a pair of nylon stockings. Whether humorous or sad, dramatic or poignant, and whether they deal with bicycles or pickles or stockings, subliminally, these stories are all about love.

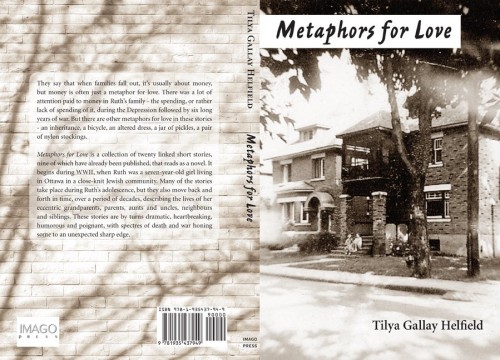

The cover’s lovely. What’s the story behind it?

I love the book cover. The photo was taken around 1940, and I feel that it embodies the nostalgic feeling of the book — it’s a home where the family lived in that particular neighbourhood at that particular time. The photo had to be enlarged and enhanced for the cover, but I left in the water damage at the bottom and the sun spots on the upper right corner.

The back cover has a repeat of the brick pattern of the house, overlaid with the shadows of tree branches — a visual reference to a scene in “Overture,” one of the early stories, in which I describe the pattern of the shadows of maple branches on the brick wall.

What benefits were there in having had some of these stories published separately in journals and anthologies?

Publishers want to see chapters of a book published separately as stories. It helps to create an audience for the final product and make the public familiar with your name. And of course, when you are published, there’s the added confidence you gain with public exposure. It also gives credibility to the time and effort you put into your writing (and to the excuses you constantly make not to do something because you’re too busy writing). But not being published is equally important. Being rejected teaches you what editors want and forces you to rewrite and improve each story.

But the main joy is in the act of writing. Publication is just icing on the cake.

Do you have a favourite story in the collection, or is that like asking you to choose your favourite child?

It is very difficult for me to choose a favourite story from the collection. “Blink” has a special place in my heart because it was the first story I wrote for the collection. But “Nylon Stockings” was the first to be published. “Stars” was the most successful, appearing online at www.carte-blanche.org and then reprinted by Nelson Education in two of their publications. “Sweet Adeline” was the first story I read on CBC Radio One. And every time I read the description of the death of Ruth’s father in “Ave atque Vale,” I’m reduced to tears.

What aspects of the writing or publishing process did you find the most challenging?

Never change your computer from Windows XP to Windows 7 in the middle of writing a book! It’s a terribly steep learning curve resulting in much frustration and gnashing of teeth! Also challenging were the four proofreading sessions of the entire book that I went through before it went to the printer. Every time I did it, I found another typo! But the most frustrating thing for me was getting it set up on Amazon with all the attendant computer issues, and getting the mass mailing out, and trying to set up a book launch and readings, and all the other publicity chores I have to do to get the word out. In hindsight, writing the book was the easy part.

What was your favourite part of the process?

I love rewriting. Staring at a blank screen when I start a story is painful. But once I have a screen full of words and sentences, I can settle down, rewrite, and rewrite again, sometimes ten or twenty times, until I get that feel at the back of my neck that I’ve got it just right. Even then, I’m never satisfied. I rewrote some stories that had already been published in order to prepare them for inclusion in this book. And even now, when I see them in print, I think of all the different ways in which they could be improved.

If you had it to do over, is there anything you’d do differently?

I don’t think so. I have the satisfaction of knowing that I couldn’t have worked harder or more diligently to produce this book. I did sacrifice some personal pleasures, but not too many. My family came first, but writing was always waiting in the wings to lure me away.

How does it feel finally to hold your published book in your hands?

It’s a feeling like no other. The closest thing I can think of is holding your newborn baby in your arms. Just as you have to acknowledge the debt you owe to parents, husband, doctors, and midwives when you produce a healthy baby, I must be grateful for the workshops and writing groups, and editors like Allyson Latta and Leila Joiner, who helped me to make my book a success. My severest critics are my children, all voracious readers and excellent writers themselves, who have been unfailingly complimentary and/or constructively critical of everything I write. No one ever accomplishes something like this alone. When I realize that I have published a book, against seemingly insurmountable odds, at an age when most of my contemporaries are dead or doddering, I am most truly and humbly grateful to everyone who helped to make it possible.

♦ ♦ ♦

Tilya Gallay Helfield was born and raised in Ottawa and lived for many years in Montreal, where she wrote a weekly humorous column for The Sunday Express and The Suburban (www.takeitfromtilya.blogspot.com). She now resides in Toronto.

Her short stories and essays have appeared in carte blanche, The Fiddlehead, TV Guide, Viewpoints, Monday Morning, Winners’ Circle Seven 2000, and Living Legacies III, as well as online (www.theoccupiedgarden.com 2008). Her story “Stars,” published online (www.carte-blanche.org; Nov. 2009), was reprinted by Nelson Education Ltd. in both Canadian Content, 7th edition, and Maple Collection 2011. She voiced her story “Sweet Adeline” for CBC’s The Sunday Edition, CBC Radio One (Feb. 26, 2012). Tilya’s story collection Metaphors for Love was published by Imago Press in March 2015 .

Tilya is also an award-winning multi-media artist who has participated in solo and juried group exhibitions in Canada and abroad. Her work can be found in 27 public collections, and in private collections in Canada, the U.S., and Europe. Samples of her artwork can be seen on her website: www.tilyahelfield.com.

Also by Tilya Helfield on this website, Memories into Story:

The Writer and Artist as Memoirist

On the Air: Voicing My Memoir for CBC Radio’s Sunday Morning