“I love to write stories (I call them “scenes”) and often write them without regard for a narrative thread. For me, it’s like putting different colours on a palette before I start painting; I don’t know which colours I might need later, but I want all the options.”

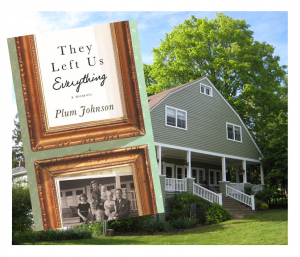

PLUM JOHNSON is an award-winning author, artist, and entrepreneur living in Toronto. She was the founder of KidsCanada Publishing Corp., publisher of KidsToronto, and co-founder of Help’s Here! resource magazine for seniors and caregivers. Her best-selling memoir, They Left Us Everything, won the 2015 RBC Charles Taylor Prize for Nonfiction. The book was also a finalist for the 2016 OLA Evergreen Award, shortlisted for the 2015 Kobo Emerging Writer Prize for Nonfiction, and longlisted for the Leacock Medal for Humour. Published in Canada in 2014, it will be released in the U.S. this July.

Participants in my memoir writing workshops and courses often speak fondly of They Left Us Everything, which resonates with readers of more than one generation. After her mother’s death, Plum took on the task of sorting what was left behind in the family’s grand twenty-three-room home on the shore of Lake Ontario in Oakville — fifty years’ worth of belongings and the poignant, humorous, and often complicated memories they evoked. The Globe and Mail described the memoir as “a poetic meditation on aging, grief and filial responsibility.”

Plum had already written her memoir and was a student in my Memories into Story II course (UofT SCS) at the time it was published, and we’ve since become friends. I was honoured when later she accepted my invitation — believe me, she is one very busy person — to return as guest author, candidly answering my students’ questions about her writing and publishing experiences so far. The following is an edited version of the class’s collaborative interview.

Did you have a firm idea what your memoir, They Left Us Everything, would be from the start, or did you write first and then fit the pieces together?

Here’s my original pitch to the publishers: “This is a ‘Goodnight Moon’ for Adults … saying goodbye to what parents leave behind.” I had been scribbling down memories triggered by the stuff I was finding. The local thrift store was already overflowing with identical stuff, and I sensed that my generation was in an unseemly hurry to throw away the whole of the twentieth century. Why wasn’t anybody writing about this? Ten years earlier, I’d been horrified when the Taliban blew up the sixth-century Buddhas of Bamiyan. This felt similar. We were essentially blowing apart our personal history — reducing it to dust. Where was our respect for the past? So I had planned a different kind of book. But I just kept writing, and once the stories were collected, it was obvious I was grieving. The mother–daughter theme emerged, which I hadn’t expected. And the book took a different shape.

Here’s my original pitch to the publishers: “This is a ‘Goodnight Moon’ for Adults … saying goodbye to what parents leave behind.” I had been scribbling down memories triggered by the stuff I was finding. The local thrift store was already overflowing with identical stuff, and I sensed that my generation was in an unseemly hurry to throw away the whole of the twentieth century. Why wasn’t anybody writing about this? Ten years earlier, I’d been horrified when the Taliban blew up the sixth-century Buddhas of Bamiyan. This felt similar. We were essentially blowing apart our personal history — reducing it to dust. Where was our respect for the past? So I had planned a different kind of book. But I just kept writing, and once the stories were collected, it was obvious I was grieving. The mother–daughter theme emerged, which I hadn’t expected. And the book took a different shape.

How did writing this memoir affect your perceptions or understanding of your mother?

Writing has a way of clarifying thoughts, and writing about my relationship with Mum changed everything. It softened my heart. The more I learned about her, the more understanding I had. Growing older myself helped, too, because I recognized how aging had affected her behaviour. She was a young person in an old body, and she hated the disabilities. As we sifted through the debris, there were many revelations. The most important for me concerned the mother–daughter theme.

Mum had always raved about the close relationship she had with her own mother. This unspoken comparison cast ours in an unflattering light. But after Mum died, I found many, many letters written by Granny throughout Mum’s childhood. Once I connected the dots, I realized that Granny had been away for most of Mum’s young life, travelling the east coast with her frail eldest daughter searching for a cure for her diabetes. After her sister died, Mum went away to college, then overseas to war where she married Dad, moving first to the Far East and then to Canada. Mum and her mother were rarely together! Their relationship was based almost entirely on letters — it’s why we found so many. No wonder their relationship was idealized! How can you scream at someone who’s not in the room?

During the writing, what pulled you, day to day, to the page?

I felt compelled to write They Left Us Everything. When I get on the right track, no motivation is necessary. I was able to write non-stop — sometimes for 17 hours a day — for over a year. The hard part is when I start something and don’t feel motivated. When this happens, I keep researching, hoping for a spark. Sometimes it feels like I’m wading through mud. That’s when I remind myself that lying fallow is important too. I read voraciously — usually three books a week. Mornings are devoted to writing, and I usually have several manuscript ideas on the go. I flit among them, depending on my mood. It’s like having several horses in the race, waiting to see which one might cross the finish line.

Which was more difficult: the initial writing, or choosing what to include or exclude?

I love to write stories (I call them “scenes”) and often write them without regard for a narrative thread. For me, it’s like putting different colours on a palette before I start painting; I don’t know which colours I might need later, but I want all the options.

I was once criticized by an editor for writing “pearls on a necklace,” but I actually think it’s an appropriate way to begin writing memoir. Life is made up of scenes. Each scene is a “pearl.” Eventually you’ll have a boxful of them – some beautiful, some ugly, some quite ordinary – but then you can pick and choose. The “string” is the narrative arc, and the “necklace” is the finished book. “Killing your darlings” is generally the editor’s job.

When writing memoir, how do you know if you’re adding too much detail?

Detail is so important. There’s no such thing as too much — until the editing phase. This is when you can stand back and look for the most essential ones and cull the rest. I find that reading the manuscript aloud helps. If you get bored, the reader will too. My favourite creative writing guru, the late William Zinsser, encourages us to look for the one unusual detail that cements the image in the reader’s mind. (He also encourages writers to delete adverbs! I remember reading this after I’d completed my manuscript, so I rushed back in to do it and found he was right — it improved everything!)

“Granny’s music box is an antique automaton. When the crank is turned, porcelain dolls play with their toys on Christmas morning to the tune of the German Christmas carol, “O du fröhliche.” It was purchased by my great-grandfather, Emil Otto Nolting, at FAO Schwartz, New York, in the 1890s we believe.”

Was there anything you considered to be off-limits — aspects you knew you wanted to keep private for yourself, a family member, or a friend?

I try not to self-edit as I write. I leave that to the editors. Most experiences are universal, so I don’t see the benefit of keeping “secrets” in a family. It seems to me we can only learn from each other.

I had included a scene about a traumatic event that got edited out — not by me, and not because it was “off-limits,” but because it “interrupted the flow of the narrative” and was considered too jarring in context. I’ll probably save that for a different book!

After reading your memoir, were any friends or family members displeased over their portrayal, and if so, how did you respond? Was it something you were concerned with while writing?

I wasn’t prepared to sacrifice any relationship for a book, so I sent family members the draft manuscript ahead of time, promising to delete anything they found hurtful or inaccurate. My brother Robin’s draft came back with “Fiction!” scribbled down some of the margins. He’s the family historian, so he’s a stickler for detail. When I’d write back, “What do you mean, ‘Fiction’?” he’d say, “You didn’t find that in Dad’s desk – you found it in the filing cabinet!” So I’d write back, “Oh, for God’s sake – that doesn’t matter!” And he’d write, “Do you want my help or don’t you?!” Sometimes, I’d write, “Good catch — thanks!” Other times I’d write, “You weren’t even there!” or “Who are you, anyway?” His daughter asked if she could keep that draft, because she loved it so much. She said our whole sibling dynamic was scribbled down the margins, and it fascinated her.

My biggest concern was for those I didn’t include! I found myself trying to include every single grandchild in at least one scene so they wouldn’t feel left out, but this became too unwieldy, and eventually I gave up.

You are an artist as well as a writer. Do you see similarities or differences between these creative practices?

All art comes from the same creative source, and I find them equally fulfilling, whether I’m writing or painting or sewing or baking! I’m just trying to say something — to express myself. For me, the process is the same: starting with the broad strokes, then adding the detail, and finally standing back for the “edit.” I find the editing just as fascinating as the writing — and often more challenging.

Which medium offers you a path to your fullest creative expression? Or does it depend on the project?

It depends on the project, but I sometimes combine painting in my writing. I often see words as colours, and sometimes I’ll do a quick sketch or a “mapping” of events. I remember wondering from a young age why adult books weren’t illustrated. Some of them are now — but they’re called graphic novels.

In They Left Us Everything, we see that you, your mother, and your daughter possess a creative streak that does not seem to be shared or even appreciated by your father. In what ways, if any, did your father influence your writing?

Dad’s creative outlets were gardening and music — he played the piano at night. He also painted watercolours at his cottage. But he never saw these things as serious “career-worthy” pursuits. How could he, given his impoverished upbringing? In my final year of high school, I was awarded the Art Prize during convocation, and I remember feeling so embarrassed – mortified that this was “the best I could do.” Dad was watching from the audience, and I felt I had shamed him. Why couldn’t I have won the Latin Prize? So, although Dad’s attitude (and the attitude of society in general) affected my self-esteem, I thank him for the genes he gave me. All of us got a double dose, one from each side of the family. I’m still not sure if it’s a blessing or a curse: Dad was right — it’s almost impossible to earn a living in the arts. But it’s given me great happiness.

Speaking of earning a living, it’s been much in the news that writers and others in publishing (not to mention the arts generally) are undervalued for their efforts. Have you experienced this since publishing your memoir? Do you believe there’s a shift in attitude on the horizon?

Writers traditionally get income from four streams: freelance articles, book royalties, speaking fees, and Access Copyright, which distributes royalties from photocopying. Oh — and I forgot about the tips from waitressing jobs!

The Writer’s Union recently published the results of their income survey, and it’s sadly true: most writers’ incomes fall way below the poverty line (under $12,000). I don’t think there will be a shift in attitude until writers refuse to work for free. This is a double-edged sword, because writers want to see their work published. But very few publications pay. Online sites almost never pay.

Writers are often shy by nature, yet publicity requires that we travel and speak to promote our work. Although writer’s festivals are good about paying honorariums, for most other events, including at libraries, the expectation is that we will do this for free. Last year I spoke on average four days per week for nine months. It meant I had no time to write and no income. One evening I was the keynote at an event for 150 people where I discovered each guest had paid $85 to hear me speak. (They also got some chicken.) The MC said it was the biggest turnout they’d ever had. Then he presented me with a bottle of wine. Another time, I was given a letter-opener. That’s when I established a speaker’s fee.

I never charge for book clubs, though, because it’s a pleasure to meet readers, and I feel grateful to be invited into their homes.

What was the most challenging aspect of writing, publishing, or promoting your memoir?

Plum Johnson (left) at an informal luncheon with fellow students from Memories into Story II, including Jayne Townsend (right)

The most difficult aspect was my lack of confidence! I was going for the brass ring with no proper training, and I felt like a fraud. A high school teacher had once shouted, “Don’t write until you have something to say!” I worried that nobody would want to read what I had to say. Then I worried that I’d be vilified for what I had written.

Eventually, I drew a cartoon of how I was feeling and pinned it on my bulletin board. I’m standing like a scarecrow with a row of black crows on my shoulder. One crow says, “YOUR WORK SUCKS.” Another says, “LET’S EAT HER FOR BREAKFAST! CAW-CAW-CAW.”

Once the book was published, I worried about promoting it. I had to overcome my fear of public speaking. The worst question I could imagine was, “Tell us what your book is about.” One year later, during the final week-long run-up to the RBC Taylor Prize, I was sitting on a stage with the other four finalists waiting to be questioned by the moderator. He turned first to M.J. Vassanji, who’d already won two Gillers and a GG for his previous works. “So, Moyez, could you tell us what your book is about?” There was a long silence as Moyez’s face darkened, and then he said, “I hate that question!”

What do you enjoy reading? Have any particular memoirs or works of fiction inspired you?

Most of the books beside my bed are memoirs — I love them. To me, they are the literary equivalent of Reality TV, which is why I think their popularity continues to grow. I’d recommend old classics — like All Over But the Shoutin’ by Rick Bragg (for his ability to capture dialogue); Treetops by Susan Cheever (for the risks she takes in her unflinching portrayals of family members); Gift from the Sea by Anne Morrow Lindbergh (for her genius in teasing out life lessons from a short retreat); My Father’s House by Sylvia Fraser (how to write about painful family secrets); and new ones like H is for Hawk by Helen MacDonald (for her exquisite use of descriptive language); Nocturne by Helen Humphreys (for the way her prose always sings like poetry); One Bird’s Choice by Iain Reid; Prisoner of Tehran by Marina Nemat; and, of course, The Glass Castle by Jeannette Walls.