Richard Gilbert always had one foot in the furrow.

His father lost their family farm in Georgia when Gilbert was six years old, and while growing up in Florida, he fantasized about one day reclaiming it. As an adult, he wonders whether he can actually cut it at farming on a tight budget or whether he is simply looking for a romantic backwoods adventure.

A journalism degree from Ohio State takes precedence, but he determinedly keeps agriculture as his minor. Then he meets Kathy, a lecturer at the university who has lived her entire young life on an Ohio farm. They marry, and Kathy gamely encourages Gilbert’s agrarian interests, which begin with a five-acre plot in an Indiana university town where she lectures and he is an editor.

In Shepherd: A Memoir, Gilbert intersperses his personal journey back to farming with remembrances of his father’s experiences searching for a farm after the Second World War, creating a story within a story. Gilbert is intrigued by his father’s published book about post-war experimental hydroponics and family lore about early trials with beef farming. From flashbacks, it’s clear that Gilbert’s father is in many ways an enigma to his son but also a man he respects and by whom he’s influenced.

When Kathy earns a promotion to a university in Athens, Ohio, in the poor but affordable Appalachia region, their search for farmland intensifies.

Regional landscape is an integral character in Gilbert’s story. The Appalachians are an area of biodiverse undulations, white mists hanging over wooded ridges. They are also characterized by high unemployment, low income, and poverty. When a unique seventeen-acre farm comes up for sale, the couple jumps at the chance. They name it Mossy Dell.

But from the start, an assemblage of local characters, entrenched in the old ways, emphasizes the differences between the couple and their new neighbours. Gilbert and his wife have a hard time maintaining their privacy and feel out of step with locals, who are interconnected, curious, and often opinionated and suspicious. They receive mixed advice from the real estate agent, the barber, and others, and are often disappointed by lax commitments for hired services.

Gilbert does his homework and concludes they can manage sheep farming on his small plot. He works hard to convert acres of fescue to clover and blue grass for the Katahdins variety of sheep he plans to buy. His first big expense is a tractor. Up to this point he has felt in control, although frustrated at times. But now his family must buy a Jack Russell terrier for hunting varmints, eliminate snakes, tear down a cabin to build a house, and check out overgrown fence lines. There are drainage issues to overcome and derelict outbuildings to clear.

So begins his race against the demands of his day job, the seasons, and the clock.

Casual observers driving past a pastoral scene see only the tranquility of sheep grazing in a field. Most of us have no idea what diseases they are prone to or the genetic markers that strengthen or weaken a breed. We don’t think of the diet they require, the predators they evade (or don’t evade), and the stressful days and nights of lambing and castration season.

There are unexpected tragedies with the sheep. And then there are the cut power lines, mould in the house, extra interest on construction loans, maxed-out credit cards, and desperate measures to pay down debts. They have to buy a Pyrenees dog to protect the sheep from coyotes and wild dogs. At one point, the family faces a cicada infestation.

“Something is always going awry, getting out of control and otherwise cheating one’s fantasies of a farm,” writes Gilbert. Yet he cannot resist trying to make his dream a reality.

Gilbert often reflects on the difficulties of being a harried editor and a part-time farmer, and spending too little time with his family. He analyzes these moments of doubt, questioning his motivations and stamina. At many points he compares his successes and failures to that of the elusive father figure he reveres but does not completely understand. All this takes a toll on his health and strains the reserves of his wife and children.

Gilbert’s prose is vivid and sensory, as in this excerpt conveying his exhaustion:

“A scrawny shirtless young man with a crop of sandy hair rode a trencher, its blade churning three feet into the ground through baked soil, roots and a layer of shale; it spit the pulverized mass to the side. The trench was bone dry. I squatted, greasy with sweat, in the trencher’s floury wake and connected pipe. Sweat rolled off my face into the dust. Cicada screamed. Wilted grass crunched underfoot. The trencher, shuddering and disgorging a gluey diesel odor, radiated in its own heat. The kid stuck inside became woozy, then faint and disoriented. Daniel pronounced him a victim of heatstroke and shut off the machine.… The hills had turned my legs to rubber. My feet throbbed, and I moved in slow motion. My shirt was so wet I could see through it; sweat saturated my leather belt and soaked my pants to the crotch. I went home to the hilltop, fed the kids, and returned.”

Through it all, the author makes his reader care about the occupational and personal challenges of farming. I found myself rooting for him and commiserating with him over his disappointments. I’m left wondering if after this experience, his children will ever have the urge to go back to the land as their father and grandfather did.

Shepherd: A Memoir (Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, 2014) was a nonfiction finalist for the 2015 Ohioana Book Award.

MARY E. McINTYRE, a member of Life Writers Ink, has published in textbooks, journals, anthologies, and newspapers, and has been a finalist in short story contests. See her blogs: Washburn Island: Memoir of a Childhood: http://maryemcintyre.wordpress.com, and Camera Combo (photography and commentary): http://cameracombo.wordpress.com.

RICHARD GILBERT was the guest author for a session of my University of Toronto SCS course Memories into Story II (advanced; online). Watch for an in-depth interview with him soon on this website.

For more about this memoir and the author, click here. To purchase Shepherd online, visit Amazon.com or Amazon.ca.

Mary, Thank you so much for this discerning review of my book—and Allyson for running it. This is one of the most complete and insightful reviews I have seen, and I appreciate it. Your care as a writer shows in every word . . . Richard

Richard,

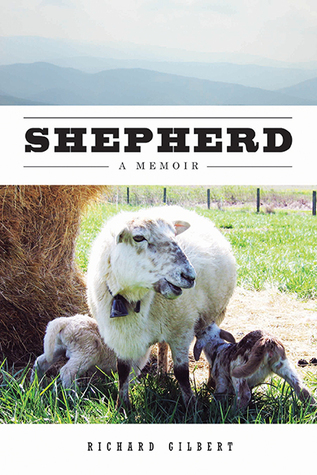

Your voice and writing style is honest and pleasing. The photo on the cover is a complement to your title. You framed your relationship with your father within the larger story about Mossy Dell. That was an interesting technique.

You wrote respectfully of your dad, and everyone else, although understandably you’d had it with a couple of “neighbours.”

I learned so much about the farming culture, especially about sheep. About a month ago I was travelling north of Barrie, Ontario when I noticed a sign nailed to a fence, “Katahdins.” Until I read your book, I’d never heard of them. I thought of you immediately.

I hope you have continued success with your memoir.