by Allyson Latta

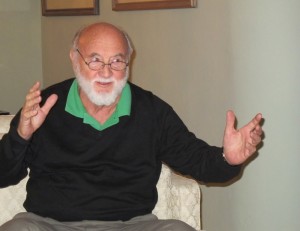

Dan Gilmore speaking at Sabino Springs Writers’ Retreat in Tucson, Arizona, January 2010. (Photo: Mary E. McIntyre)

DAN GILMORE has published a novel, A Howl for Mayflower (Imago Press, 2006), and two collections of stories and poems,Season Tickets (Pima Press, 2003), and Love Takes a Bow (Imago Press, 2010). He has received awards from the Raymond Carver Fiction Contest, the Martindale Fiction Contest, and Sandscript. His poems have appeared in Atlanta Review, Aethlon,and numerous other journals. Several were anthologized in Loft and Range (Pima Press, 2001). His novel has been adapted as a stage play and will be produced in 2012. Dan continues to work on poetry, as well as a novel set in a wedding chapel in Reno. He lives in Tucson, Arizona.

“My life is not unique, secret or precious. The way I talk about it, if I’m lucky, is unique.” —Dan Gilmore

AL: Dan, you’ve written poetry, lyrics, short memoirs, a novel, and are now developing a stage play. Which comes first for you, the idea or the form, and how do you know when the form is “right”?

DG: Other than time and complexity I don’t feel like there’s a major difference between the various forms. Poetry takes the least time and is most complex. Plays and novels take the most time but are less demanding. The primal form is writing, writing anything. Poems turn into short stories, short stories into novels, novels into plays. I seem to have little control over that process. However, my best ideas always come from the act of writing. My muse is fickle. She shows up only when I’m putting words, almost any words, page after page of words, on paper. Poetry or novels or plays, she’s the same—contrary, cranky and unpredictable. The withholding scamp! She told me in one of her tirades that the primal “form” is me sitting at my desk clutching a number 2 pencil and moving it across the page. I’m thinking of asking for a divorce, but we’ve been at it so long—old habits, a few pleasant moments, an occasional tumble in the hay, that type of thing. Oh, regarding when it feels right. I never know when it’s right. It just feels—less wrong. That’s when I give it to a couple of semi-trusted readers. If they like it, I tend to gear down my compulsion to make further revisions. If they don’t like it, I send it to a literary magazine to prove I shouldn’t trust my friends. If the editor rejects it, I’m depressed for weeks.

AL: Most of your writing is rooted in life experience. How far do you venture from the facts for art’s sake?

AL: Most of your writing is rooted in life experience. How far do you venture from the facts for art’s sake?

DG: A lot. My memory is faulty, thank God. My false and selective memory enables me to mythologize my life by remembering and misremembering a limited number of stories that help me explain me to myself. If I had perfect recall I’d be psychotic or a really successful contestant on Jeopardy. Freud was notorious for “fictionalizing” his case studies because rearranging, compressing and selecting made better narratives. Read them. The man is much more a storyteller than a scientist. When I’m working, I consider everything I write as fiction, although most of what I write is grounded in my personal delusions of truth.

AL: How do you summon the courage to write about personal subjects, including painful experiences, and do you find you have to allow time to pass before you can do so?

DG: I don’t feel courageous. My experiences seem about the same as other humans’. I struggle, I experience pain, I hate and love, I laugh when I should cry, cry when I should laugh. I lie and cheat, I’m loyal and abysmally disloyal, I’m hated and loved (sometimes by the same people), I’ve been abused and abandoned, I’ve done my share of abusing and abandoning, I change my strongly held opinions almost daily, I’ve experienced catastrophic loss and incredible good luck. I believe other people have done about the same. So, what’s to confess? Certainly nothing new. My life is not unique, secret or precious. The way I talk about it, if I’m lucky, is unique. When I avoid my own uniqueness, my own way of seeing the world, readers don’t and shouldn’t trust me. And yes, it takes some time for buds of truth to blossom into anything resembling art.

AL: In your talk at my Sabino Springs Writers’ Retreat in Tucson, you dispelled some misconceptions about writerly “inspiration.” Can you reflect on that here?

DG: Most of what I write is crap, pages and pages of crap. But crap seems to be the only payment the muse will accept as proper compensation for her visit. She demands to see the hard work because she suspects I’m really a pretender. God, I wish I could slip a lie past her once in a while, that she accepted wanting it really bad instead of actually writing, that she was empathetic enought to show more respect for waiting, sincere prayer, and the fact that I’m too old to waste my time writing all this drivel. I think she has it in for me. Beckett must have been referring to the same problem when he wrote, “I can’t go on. I must go on.”

AL: What three abilities do you believe a writer most needs to nurture?

AL: What three abilities do you believe a writer most needs to nurture?

DG:

Find the discipline to write every day. This means rain or shine, heartbroken or happy, tired or retired.

Develop your voice. I keep losing mine. I have to be careful about what I read. I read Rilke (one of my favourites), sit down to write, and end up sounding like a horribly cheap imitation of this great poet. Other writers always seem so much better than me. I’d rather be them instead of me. So I have to keep reminding myself that I’m stuck with me, that my only uniqueness as a writer is my voice. To do this I read my own books to hear my own voice. Then I do my best to imitate myself.

Avoid literary sprawl. When I get stuck I tend to go wider instead of deeper. I add some new character or what I believe to be a clever plot twist. I revert to sitcom humour. I tell myself, this is great stuff. But in fact, this is literary sprawl. A Howl for Mayflower was over 600 pages before I gave it literary liposuction and managed to reduce it to around 200. In the beginning when I’m searching for the narrative thread, sprawl is good. But it is usually boring and shallow and often hides the core story. When I rewrite I try to avoid moving horizontally. I reflect, back-write, rewrite, riff on a key word or phrase, remove every darling, and do anything I can to find the real story and present it with clarity. This sometimes deepens my writing, reveals something I hadn’t known before, maybe something I needed to say and had been avoiding. Writing that doesn’t surprise me is almost always suffering from sprawl.

Dan Gilmore captivated participants during my writers’ retreat in Tucson, Arizona, earlier this year. Love Takes a Bow, a collection of poems and a short memoir, was recommended reading during the retreat.

Hello to Dan.

I took the photo of you in Tucson, and if I hadn’t been there, that twinkle in your eye looks like a fishing tall tale of the one that got away.

I learned a lot from you in Tucson, and Allyson’s interview reminds me of the gems that inspired me then.

Your quote is meaningful to all memoirists: “My life is not unique, secret or precious. The way I talk about it, if I’m lucky, is unique.” I recall your honesty in your writing, and that frank view of the people and places in your life is unique.

I love your book A Howl For Mayflower.