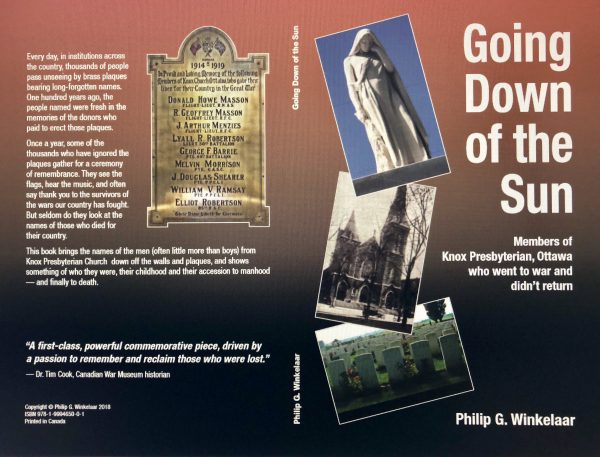

by Philip G. Winkelaar

“I made an appointment with the niece I’d been told about, and was rewarded with tea and some family stories. It turned out that she had documentary evidence in the form of letters — from the deceased and his brothers, who had also served. In that moment I realized I could — in fact should — dig deeper.”

For years I hardly noticed the brass plaques on the walls of my church that list the people who volunteered and those who died in the two world wars. Except, that is, on Remembrance Sunday, when we have a special ceremony at which the names of the dead are read out and a minute of silence observed. The sounding of the Last Post or the piper playing a lament always moves me.

One year, after that solemn service, as I contemplated the nine names on the World War I plaque, a woman pointed to one and said, “That man’s niece lives across the lane from me.” I looked at her, and at the plaque, and recalled a recent newspaper article about the volunteer refurbishment of that soldier’s grave in England, nearly a century after his death.

In my career as a family doctor, I was continually reminded that one person’s illness affects many others — the family and friends, employers and co-workers. So, of course, must the deaths of these soldiers have affected those around them — why else would the members of the Knox Presbyterian Church congregation have spent effort and funds to place these memorials? That led me to ask other questions: What were the people like — were they destined to be heroes, or were they ordinary people? What kind of family did they have? How did they grow up? Since they were all members of the church, should I assume that they were all paragons of virtue? I had served briefly in the armed forces, and knew how unlikely that scenario was!

I had visited military cemeteries in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, and knew that during both world wars soldiers were buried in the land where they were killed. Their bodies were not brought back to Canada, as they are now. So I asked myself, where are their graves? And how did they die? Were they all killed in action? Were some of the deaths due to so-called “friendly fire”? Did some die in accidents? Throughout history, deaths in time of war have as often been due to disease as to wounds. Was that true of some of these men?

I decided to delve into these questions first by reviewing the newspaper article about the grave rehabilitation. I made an appointment with the soldier’s niece I’d been told about, and was rewarded with tea and some family stories. It turned out that she had documentary evidence in the form of letters — from the deceased and his brothers, who had also served. In that moment I realized I could — in fact should — dig deeper.

My research started with church records. Some were held at the church itself and others in the City of Ottawa Archives. The soldiers’ service records are held by Library and Archives Canada. Many of them have now been digitized and are online.

With so many records available, I realized that I didn’t need to restrict my investigations. I could expand these to include all the soldiers on the plaque. City directories revealed the neighbourhoods where they grew up, and the occupations they (or in most cases their parents) pursued. Ancestry.ca was another source of information, as were birth, marriage, and death records, all of these giving insight into family backgrounds.

School records from a century ago have largely disappeared, but if you don’t shoot you can’t score, so I tried all the sources I could think of and was rewarded with data that allowed me to visualize not only the young men as students but also their school environments, which were quite different from that I was familiar with and even more changed today.

Regimental histories, written years or decades later, can paint a picture of the events of battle and the conditions the men faced. Regimental war diaries were written within hours or days of events, and although sadly clinical and short, they also illuminate the actions.

Veterans Affairs Canada maintains a website devoted to remembrance, called the Virtual War Memorial. This site has additional information, and some photos, provided by interested parties.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission is responsible for maintaining all overseas war graves (an exception was the one being refurbished) and gives basic information about the location of cemeteries and details of the location of individual graves. Photos of the graveyards reveal the serenity in which the fallen now lie.

Admittedly the mass of information was intimidating. I stumbled on contradictions between sources, which had to be resolved, and I had to sort out the relevant from the merely interesting. The latter created rabbit holes into which one could dive, emerging hours later with anecdotes entirely unrelated to the matter at hand.

I began by writing brief outlines of each of the men on the plaque. I then refined these. On the basis of some good editorial advice and criticism, I realized that the backstory I found fascinating had to wait until I had presented the individual, and that some of what I found interesting was likely to be boring to a reader.

A major challenge cropped up – I knew not every soldier was without failings, some failings, though, might be more sensitive than others. Should I reveal those? Then I had to ask myself, was this to be a hagiography or a true story? Ultimately I opted for the latter; though I knew I risked being accused of blackening someone’s memory, I declined to whitewash it.

Next, since I was dealing with nine individuals, I had to decide the sequence in which to present them. Age? Date of enlistment into the army? Date of death? Alphabetically? Or something else? I finally decided to order them as they appear on the plaque. The church members must have put some thought into the order. Who am I to gainsay their decision?

Two brothers were among those who died — should their stories be told together, or separately? Because a single event can affect individuals differently, it seemed to me it would be unfair to one or the other to combine them, so I had to decide how much needed to be repeated in both stories.

The same question came up when dealing with men in the service who had experienced the same events – they were individuals, each seeing the event from their own point of view, so there was bound to be a certain amount of repetition. The same was true of school events. Ottawa was a small city, and many of the volunteers went to the same schools at the same time. And, of course, many of them attended the church and Sunday school together. Did they have other common threads?

I belong to a writers’ group, and I presented my stories there. Based on others’ response and advice, I revised each of the profiles. Again. And again. I sought advice at a writers’ retreat — and revised everything again. I sought affirmation from my spouse — and revised some more.

I chose a title. Going Down of the Sun is a phrase from the “Ode of Remembrance,” taken from Laurence Binyon’s poem “For the Fallen,” first published in The Times of London in September 1914.

Perfection will always elude a writer. But the centenary of the 1918 armistice takes place this year, and I had researched and written the stories for all those who died in the Great War, 1914 to 1918. What could be a more appropriate time to make their lives known once again? So I went ahead and published my little book, finding my own printer and paying for it myself. I was so immersed in the writing and rewriting that I gave no thought to finding a sponsor, nor even to the issues of marketing. I did send the manuscript to an eminent military historian, Tim Cook, for comments. I was gratified that he had the time to read it and in fact reward the work that had gone into the book with genuine praise.

I finished it. I am proud of what I did. I am happy, and my wife now sees me again. But I find myself looking forward to 2020, the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, knowing that the men commemorated on another plaque also deserve to have their lives chronicled.

That will keep me out of trouble.

♦ ♦ ♦

PHILIP G. WINKELAAR’s career as a family doctor spanned nearly forty years. For fifteen of those he served in the Canadian Armed Forces, regular and reserve. He has always been interested in learning about people and hearing their life stories. Retirement gave him the opportunity to delve more deeply into those experiences. A lifelong Presbyterian, he is also an elder at Knox Presbyterian Church in Ottawa, where he lives with his wife Linda.

PHILIP G. WINKELAAR’s career as a family doctor spanned nearly forty years. For fifteen of those he served in the Canadian Armed Forces, regular and reserve. He has always been interested in learning about people and hearing their life stories. Retirement gave him the opportunity to delve more deeply into those experiences. A lifelong Presbyterian, he is also an elder at Knox Presbyterian Church in Ottawa, where he lives with his wife Linda.

♦ ♦ ♦

The Launch!

The launch for Going Down of the Sun will take place at Knox Presbyterian Church, 227 Elgin Street, Ottawa, 12:30 p.m. on Sunday, November 4, the beginning of Remembrance Week, in honour of the 100th anniversary of the end of World War I.

To purchase a copy ($22.95 plus mailing), please contact the author at GoingDownofSun@gmail.com.