Guest post by Kyo Maclear

I thought … last night, something very profound about the synthesis of my being: how only writing composes it: how nothing makes a whole unless I am writing …

—Virginia Woolf

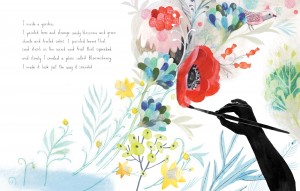

Illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

In 1941, on this day, March 28, Virginia Woolf put on her overcoat, filled its pockets with stones, and walked into the River Ouse near her home and drowned herself. The rest is history.

As we witnessed with David Foster Wallace’s suicide, a tragic end can cast a sad pall over an entire life’s work. In Woolf’s case, there is a tendency to read her life retroactively, to look for signs of lethal melancholy everywhere. We gaze at the photographs, which seem always to show her standing alone, under storm clouds (even when she’s accompanied, even when it’s sunny). Some of us feel the weight of stones in her novels. Others cannot read her letters and diary entries without feeling apprehensive for her. For many years, my primary image of Virginia Woolf conjured her as a sad be-cloaked English shaman figure with a faraway stare.

One of the stories we tell about Woolf relates to her “sensitivity.” There was her keen sensitivity to criticism, her sensitivity to the war and the death of her mother, her sensitivity to the conditions facing women writers. The intensity with which Virginia Woolf experienced life seems at times agonizing. Reading her autobiographical Moments of Being, it is the depth of feeling that startles, the unsettling sense that nothing was not absorbed. The writing still feels shockingly contemporary and vulnerable.

It is hard not to wonder about the price of such sensitivity. I recently came across a fascinating essay (titled “Against Narrativity”) by British philosopher Galen Strawson in which he essentially argues against memoir: “My own conviction is that the best lives almost never involve this kind of self-telling.” He believes (as the Buddhists do) that contentment arises from the ability to immerse oneself in the present without placing each moment and episode in an autobiographical frame. For those of us who write from personal experience (whether that writing take the form of memoir or fiction), this may be a troubling and bizarre sentiment.

Illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Are the mental habits of the memoirist conducive to happiness? Do we risk distancing ourselves from our experiences by writing about them? Is it possible to abstain from self-narrativization?

We all self-tell to varying degrees. Literature would be nothing without the great generosity of writers who have divulged, examined, and dissected their lives in the hopes of sharing some tangled and illuminating insight. But is there a price to pay for standing back, for mining slivers of meaning from the residue of an experience?

Patti Smith, author of the memoir Just Kids, argues that the writer can never enjoy the equanimity of the non-writer. “You never can be normal,” she says. “You go into church to pray, and you start writing a story about being in a church praying. You’re always observing what you do. I noticed that when I was young going to parties. I could never lose myself in a party unless I was on the dance floor because I was always observing—observing or creating a mental scenario.”

Woolf was a writer whose work epitomized this state of perpetual self-examination. From The Waves to On Being Ill, everything she wrote feels like a flood of revelation and reflection. It is rare to encounter such fierce intelligence and, yet, almost pathological self-awareness. I know of few other writers who have put as much faith in writing as the path to self-understanding, who have so bravely explored the writer’s consciousness and the “violent moods” of the soul. As her biographer Hermione Lee noted: “She is always trying to work out what happens to that ‘myself’—the ‘damned egotistical self’—when it is alone, when it is with other people, when it is contented, excited, anxious, ill, when it is asleep or eating or walking, when it is writing.”

While it may be true that in telling stories we risk objectifying our experiences, I think Woolf’s most significant legacy was to show that, at its best, writing could also re-immerse us in our lives. The very phrase “moments of being” emerged from her belief that there are moments in which an individual experiences something intensely and with awareness, in contrast to the states of “non-being” that dominate most of an individual’s life, in which life is “not lived consciously,” but instead is embedded in “a kind of nondescript cotton wool.” For Woolf, it was the quality of attention and wakefulness intrinsic to a conscious writing life that could take a mundane activity (such as walking in the woods) and make it extraordinary.

Illustration Isabelle Arsenault

In this age of social media and infinite sharing, I find Woolf’s distinction between “moments of being and non-being” all the more powerful. Our external moments of being have never been so available, never so shared. (Read a sample Twitter feed: “Just ate the best burrito. Now riding the Queen streetcar.” “I love eBay. Seriously. I would marry it.”) But one casualty of this will-to-share is our depth of consciousness. We have reached a point where we confuse self-reporting with genuine intimacy, where we select rushed journalism over literature, data over poetry. We have learned to surf without plunging.

I think what I appreciate most about Woolf is her willingness to lose herself in the slipstream of her writing, her courage to capture the self in its myriad and fragmentary moments. I admire her great ability to roam (both figuratively and literally) without losing her grasp on the outer world and its significance. I actually believe Virginia Woolf would have been great on Twitter. She was not lost in her own myopic swirl. For instance, in her “Sketch of the Past,” which she began in the last two years of her life, she insisted that the life-writer must explore and understand the relation between the less concrete areas of personality—the “soul”—and forces like class and social pressures; otherwise “how futile life-writing becomes.”

In other words, while Woolf felt that the really important life was “within,” she continued to embrace her outer, social life. As Hermione Lee writes: “She knew an enormous number of people and met many of the exceptional figures of her time. She listened to, and participated in, a huge amount of political discussion. She was a publisher, who worked with her husband as a business partner in the Hogarth Press. She was a close and observant analyst of the world she lived in. And she was one of the century’s most insatiable readers.”

For those of us who use social media on a regular basis, who sometimes feel that we are contributing to the noisy too-muchness of this information-saturated world, I think Woolf provides some helpful cues: “What sort of diary should I like mine to be? Something loose-knit and yet not slovenly, so elastic that it will embrace anything, solemn, slight or beautiful, that comes into my mind. I should like it to resemble some deep old desk or capacious hold-all, in which one flings a mass of odds and ends without looking them through. I should like to come back, after a year or two, and find that the collection had sorted itself and refined itself and coalesced, as such deposits so mysteriously do, into a mould, transparent enough to reflect the light of our life …”

Something loose-knit and yet not slovenly … One good phrase by Woolf can make my day. One good paragraph can jolt me from the habitual. One good book can make the world seem bright and new and mysterious again.

* * *

Kyo Maclear

KYO MACLEAR is a children’s author, novelist and visual arts writer. Her new novel, Stray Love (HarperCollins Canada/Picador Pan Macmillan Australia), and latest picture book, Virginia Wolf (Kids Can Press), were published in March 2012. She lives in Toronto.

Illustrations above are by Isabelle Arsenault of Montreal, from Virginia Wolf.

Toronto, Ontario

Canada

© 2025 Allyson Latta | Terms of Use | Privacy Policy

Beautiful article. True, sadly a lot of people perceive Woolf as a dark, gloomy figure. She also had an incredible lightness of being and an insightful mind; looking for your book, I’m intrigued… :o)

Hi Marielle. I completely agree. Woolf had so many shades as a writer. I am constantly astounded by her playfulness and willingness to push boundaries. Her book On Being Ill is so surprisingly positive about the place of illness in her life and how it allowed her to desynchronize from life’s usual pace and priorities. (p.s. I do hope you enjoy my new book!)

Woolf seemed to have a highly developed sixth sense and a cracking intelligence. I suspect she was depressed too. What a lethal combination. I’m only sorry for the times she lived in, that there was no relief for her “discomfort with life.”

Regarding your statements: “We have reached a point where we confuse self-reporting with genuine intimacy, where we select rushed journalism over literature, data over poetry. We have learned to surf without plunging.” People critical of memoir perhaps do not realize how difficult it is plunge into our memories and share them with others.

This was a lovely, thoughtful article. Kyo, I wish you every success with your books.

Thank you for your comments, Mary. I am in awe of memoir writers and the brave vulnerability involved in sharing one’s life stories and experiences. I recently read Jeanette Winterson’s memoir (WInterson is also a great Woolf admirer) and was so struck by the raging and raw courage she showed throughout the book. As a novelist, I found it particularly fascinating to contrast the memoir version of Winterson’s adoptive mother to the fictional version (in Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit.)

A perceptive piece.