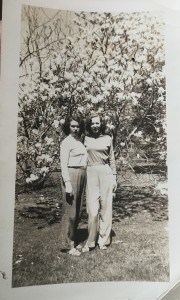

This is Marilyn, at seventeen.

I think she’s beautiful, far more so than I remembered growing up. Why did I not see that?

I think it’s that she valued brains and ambition over beauty. Though, she once confided she spent a whole summer trying to style her hair after the 1940s movie actress Veronica Lake. She treated beauty as something transitory, a phase we might go through, a costume we might wear, never anything lasting or meaningful.

§

This is my mother, Marilyn, and her best friend, May. They stand beneath a flowering magnolia tree, tucked into each other; it’s an intimate pose, my mother’s body turned toward her friend. Yet what is most startling is her gaze: my mother stares straight into the camera, exactly the way she would face her life. There is confidence, almost defiance, in the proud tilt of her chin.

They are dressed alike in wide-leg trousers and turtleneck sweaters, even down to the exact same style of shoe. Their hairstyles, too, are alike, thick and wavy and parted on the side. Though the photo is black and white, I know my mother’s hair is the colour of mahogany and that it resists her attempts to contain the wild curls.

I marvel at the sameness of these two, and I wonder about it. They could be sisters. Looking at this photo, I imagine they’ve run away for the weekend.

On the back in her perfect handwriting, she wrote: May and I, Rochester – 1949.

This photograph was taken the year after her beloved father died and she’d had to quit school and go to work in a factory. She was lonely as a child, with no brothers or sisters. My grandmother came from a large family; a serious Victorian, Baptist raised and fearful of change, she tried to imbue her daughter with an unnatural reserve, an emotional constraint that my mother resisted her whole life.

In the photo, my mother’s expression hints at an outer toughness she’s learned to wear. She dangles a cigarette from one hand, as if she’s been smoking for ages. I can only imagine my grandmother’s livid response— a lady would never smoke. My mother would laugh; she always described herself as more of a broad than a lady. It took me half my life to appreciate what a gift that was to both of us.

§

This is my mother, Marilyn, at the beginning of her adult life, a life that would lead to two marriages, four children, a career as the first female store manager in the history of Zellers, and a terminal diagnosis of breast cancer. She was a feminist without ever uttering the word; she prided herself on her work ethic, declared she worked “as hard as any man,” and never took a dime she didn’t earn: she received no social assistance, no alimony, and no child support.

She who had been the apple of her father’s eye would spend a lifetime battling for equality. Sometimes it seemed she preferred men, understood them, and was more aligned with their ambitions and desires.

Her long days were spent rushing about on her high-heeled feet, supervising retail staff and merchandising her store. She didn’t cook, or clean, or sew; she never came to a school play or a music performance; and she fell asleep on the sofa after dinner every night, because she was too tired to walk up the short flight and undress for bed.

But my mother taught me about joy too; she danced on Sunday mornings to Aretha Franklin’s “Respect,” and when my brother tried to close the curtains, she would holler above the music, “I don’t give a damn what anyone thinks.” And she didn’t, most of the time.

Sometimes I try to imagine her laughter, the backdrop of my childhood, the sign that all would be well. It wasn’t always well, yet her optimism was the cushion to every disappointment, every failure. In my childhood, we were always moving, uprooted for a new job in a different city. Every move she described as an adventure, an open road of possibility that would lead to her success. This is a woman who valued work over home, skill over sentiment, perseverance over help. Her heart was more generous than that of anyone I’ve ever known: she gave away more than she ever received.

§

Here, in one of a few precious pictures of my mom, I see a young woman at the beginning of a difficult life, and I imagine the mother of my youth who would say to that young girl, “You can bear anything if you put your mind to it.” And she did: loneliness, betrayal, abuse, neglect, divorce, breast cancer, and death. She taught me life wasn’t fair and then showed me exactly how to live with that.

I feel gratitude for her strength of spirit. I always thought it was something she had acquired along the way, but when I look at this photo now, her spine straight and gaze unwavering, I see it came early. She looks out at the world, unafraid. She’s beautiful, dark-haired, a little mysterious.

This is Marilyn, at seventeen. She’ll be one hell of a broad someday.

PAMELA DILLON is a writer and poet. A student of creative writing at University of Toronto, she is at work on a collection of short stories for her final project (Certificate in Creative Writing), a novel, and a few creative non-fiction travel pieces. Pamela’s short story “We Come and We Go” and her novel excerpt “As Good As Any Other” won placement in the top ten in the 2013 and 2015 Penguin Random House of Canada Student Award for Fiction, through UofT School of Continuing Studies. Pamela has been published on the CBC Books – Canada Writes website, in the literary journal Tin Roof Press, in the William Henry Drummond / Spring Pulse Poetry Anthology, and most recently, in the Globe and Mail‘s Facts & Arguments and Travel sections.

PAMELA DILLON is a writer and poet. A student of creative writing at University of Toronto, she is at work on a collection of short stories for her final project (Certificate in Creative Writing), a novel, and a few creative non-fiction travel pieces. Pamela’s short story “We Come and We Go” and her novel excerpt “As Good As Any Other” won placement in the top ten in the 2013 and 2015 Penguin Random House of Canada Student Award for Fiction, through UofT School of Continuing Studies. Pamela has been published on the CBC Books – Canada Writes website, in the literary journal Tin Roof Press, in the William Henry Drummond / Spring Pulse Poetry Anthology, and most recently, in the Globe and Mail‘s Facts & Arguments and Travel sections.

“This Is Marilyn” was inspired by Carol Ann Duffy’s poem “Before You Were Mine” and The Guardian‘s feature “My Mother Before I Knew Her” (March 5, 2016), a theme-based collection of creative nonfiction by Julian Barnes, Jeanette Winterson, and others.

Dear PAM

I am reading with tears in my eyes and rembering your mom. She was quite a woman .

Love Stella