So what of now, in this age of abbreviated e-mails and text messages? I pondered this question when I shared my father’s letters with my son . . .

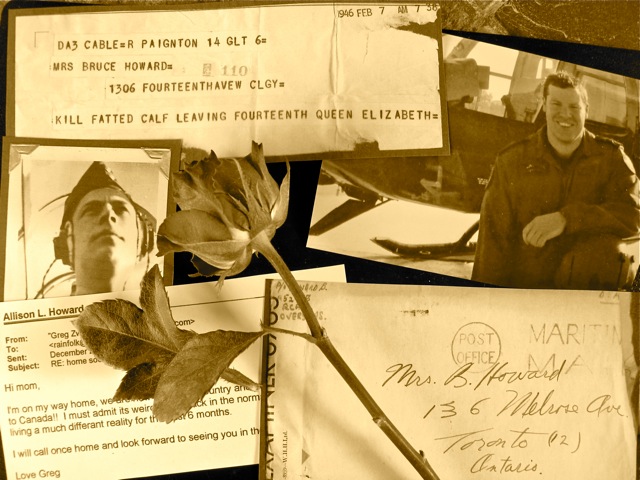

“KILL FATTED CALF. LEAVING FOURTEENTH QUEEN ELIZABETH”

My father chose these words from the biblical parable of the Prodigal Son to signal to my mother that he was homebound from England after serving as a pilot during the Second World War. She was no doubt joyous to receive that brief message, having said goodbye to Dad almost a year earlier and after only three weeks of marriage. She’d waited out his absence with his rigid Presbyterian parents who, though kind people, would abide no social life or frivolity under their roof.

Dad served as a flight instructor in Canada as part of the Commonwealth Air Training Program during his entire tour of duty, but was the victim of a military bureaucracy that, ironically, scheduled him to sail for England the day after peace was declared. The impossibility of reversing paperwork combined with the nervousness that prevailed over the definitiveness of war’s end meant that many ships continued crossing to Europe with troops aboard in the weeks after Armistice.

The “first over, first back” policy was undoubtedly fair but meant a delay for my father’s return. This was compounded by the fact that he was struck by appendicitis around the time he was scheduled to return, resulting in a long hospital stay in England.

So it was February 7th, 1946, almost ten months after the end of the war, when my father sent the telegram.

In the meantime, my mother had kept busy working in a science lab and comforting herself with Dad’s frequent, entertaining, and sometimes poignant letters, including this one written a few days into his rather luxurious crossing on the Queen Mary:

On board we have a number of civilian internees. (I don’t know why they’re aboard.) Last evening two of them produced musical instruments, a guitar and a mandolin and in a corner on deck, sheltered from the wind a little impromptu concert and singsong took place. The music played, tended toward sad, dreamy gypsy songs … It was rather picturesque there on deck with the wind blowing and everyone clustered around two nondescript characters playing sentimental gypsy songs. I sang too and thought of you and enjoyed the singing but wished I were with you. I miss you an awful lot wifey. I hope it won’t be long.

My father’s war experience was infinitely different from that of so many of the soldiers who’d gone abroad. For him the war was an adventure served with the cockiness and derring-do of one who never saw combat and was experiencing his first freedom from a religiously repressive household. But the only way we can know this is through his letters. In the absence of a journal, letters can serve as a kind of abbreviated memoir of the writer’s life — albeit focusing on just a slice of time. Often truncated, letters oblige the reader to search for meaning, context, and consequence. And in this search, family histories are constructed.

§ § §

I came across Dad’s letter and a small clutch of others recently while helping my mother move to a retirement home. Mostly written to my father and saved in an old brown envelope, they gave me a rare and personal glimpse of life in the war years. Some from buddies overseas or stationed in Canada, some from family and friends updating him on home life, they describe training, postings, convalescence, domestic life, love interests, and more.

I was often struck by the eloquence of the letters. It is hard to imagine a young man today writing of his convalescence from war wounds as did this good friend of my father’s:

I am beginning at last to feel at ease in a conv. hosp. Our new div. is not as elaborate as Divadale(?), but is more homelike and pleasant. It is smaller and the spirit here is grand. I have never experienced such companionship amongst everyone, staff and patients. The home is lovely, the surroundings beautiful. There are many small rambling green hills with patches of wild flowers, daffodils, narcissi, violets, lilacs and many other flowers. Looking out on it I think we have found Utopia. I have never seen so many different types of birds. Some of the lads caught 4 red foxes, they are pretty little animals.

We know much about the battles, the strategies, the geography, and the politics of the world wars through the glut of meticulously researched books about them. But only through letters from those in the trenches, on the battlegrounds and in hospitals, in the liberated towns and elsewhere affected by the aftermath, do we know of the personal experiences: the suffering, crushed spirits, and anger; but also the determination, camaraderie, and hope.

§ § §

So what of now, in this age of abbreviated e-mails and text messages? I pondered this question when I shared my father’s letters with my son — particularly meaningful as my son is a military pilot who has twice served in Afghanistan. He said, “You know, Mom, those letters were how we really knew about the wars and we’re not going to know about current and future wars in that personal way because no one writes real letters anymore.”

We discussed how brief e-mails sent home do not capture the essence of the grit and fear and triumph that letters once did. Yes, we are able to communicate more frequently and instantaneously, and occasional Skype calls are a luxury the families of bygone soldiers couldn’t even dream of. But so much of what we receive are only brief descriptions written in haste and with wariness of security concerns.

Probably because of the rare occurrence of actual letters, I do so treasure the description my son wrote to me shortly after his arrival on his first deployment to Afghanistan in 2005:

I’ve seen many sides of the local population. There is quite the desire to rebuild in many parts as you see new buildings going up and billboards for cell phones and the like; but, across the street you see women in Burkas and a 4-year-old kid watching a herd of goats. The people generally seem indifferent to us here as the average local is more concerned about their daily survival; however, on the other side, some have a look that they do not want foreigners on their soil. These are generally the ones who profit from the instability such as drug trafficking, which is a huge problem, and source of much of the money that funds much of the violence and pays many of the war’s bills.

The weather is hot to say the least, it’s well over 40 degrees every day and as yet there was one day with clouds. The terrain is spectacular, as mountains swell over 20,000 feet and some remain snow-capped year round. The mountains are steep and very unforgiving and a constant challenge. It really is a beautiful country.

Having recently completed a degree in Military History, my son is acutely aware of the void that will exist for future historians when they come to try to understand the personal experiences of today’s (and tomorrow’s) soldiers. This void is not unique to the experiences of war, of course — it will exist for many aspects of our everyday lives.

For while we still write, we write in a different way — e-mails, frequent and numerous, are not generally kept for permanent record; blogs detail the minute details of people’s lives, but too often lack the unselfconsciousness of those earlier letters, which weren’t written for a broad audience. Those letters weren’t spell-checked and grammar-checked and proofread; they were the honest, spontaneous thoughts and observations of the writer for the eyes of one reader, or one family — an uncensored view into a world we might otherwise never have known.

Without those letters, so many details, perhaps seemingly trivial at the time, will be forever lost to future students of history, genealogists, memoir writers, and family historians.

Dad passed away on September 11, 2002, exactly one year to the day after a traumatic event that’s part of another kind of war. That date is one on which the world acknowledges a collective pain and the importance of remembering, but for me it is also a personal time of reflection. I am grateful to have even a little of my father’s story, as told in his war letters home.

♦ ♦ ♦

Allison Howard, beside her Little Free Library. For more about this initiative, see http://littlefreelibrary.org

ALLISON HOWARD is a former social worker living in Penticton, British Columbia. Besides enjoying the many outdoor activities that the beautiful Okanagan Valley provides, Allison is an avid photographer who shows her work at galleries and other venues. She is also co-editor of A Memoir of Friendship: Letters Between Carol Shields and Blanche Howard and has published personal essays in Canadian Woman Studies and elsewhere. Allison sees a link between the creative worlds of writing and photography, and the simplicity and charm of life in British Columbia’s southern interior encourages these twin passions. Visit Allison Howard Photography.

Thank you so much for your encouragement to tell this story Allyson.

Allison,

Your essay struck a chord with me. The only letters I write now are to elderly aunts at Christmastime. I give them my truncated slice of life (your words), throwing in details that I would miss if sending an email. I try harder to find the connections I know they will want to feel from my message, the links to our shared past.

Through email avalanches, remembering is assumed when most is half-remembered, trivial, amusing and “we’ll catch up later.” What will historians do without the texture and context of thoughtful letter-writing to guide them? We are losing an old-fashioned skill, and replacing it with modernity. But unlike the hula hoop, I don’t think email is going away.

I appreciate your thoughtful analysis of a lost art.

Thank you Mary – email avalanches indeed. My son was so surprised that I had saved and printed his email he sent when he was returning from Afghanistan. That was back when emails were more of a novelty. Would I remember to do that now?

I suppose that, on the plus side, people today will leave much more in the way of photos and videos as records of their lives – though they do need to be saved in a form that will keep them available in the future. My new year’s resolution – to print out emails and photos and to make CDs of videos!

On another aspect of your wonderful essay, you rightly point out that the “first over, first back” policy was the fairest way, and a direct result, I’m sure, of what happened in WWI when it was “last over, first back”. Soldiers who had endured the entire war and all its horrors were kept in conditions little better than concentration camps for many months while reading newspaper reports of men who had not even fought being fêted as heroes back home. This led to mutinies in some cases and a young soldier from my home village in New Brunswick died along with several others as military police fired into the crowd during one of them. He was simply a bystander and his father, who had also recently lost his wife, never recovered.

Elizabeth, I had not known that. What a horror – thank you for sharing it, I’ll pass it on to my son.

What a thought-provoking essay. Thank you Allison. It reminds me, too, that (like Elizabeth) one of my New Years resolutions was indeed to print out e-mails…. January’s not over, so maybe it’s not to late to start.

And thanks to Allyson for running this lovely piece, and for all the other fascinating threads on your blog.

Thanks Barbara; printing out emails sounds simple, yet daunting!

I agree with Barbara – very thought-provoking. It made me think of my fanaticism with archiving all my electronic correspondence since getting my first personal email account. I now have over 10 years worth of emails meticulously filed on my computer (although someone once told me it was a pointless waste of time to do so). Nevertheless, 99% of it is devoid of the “texture and context of thoughtful letter-writing” that Mary mentioned above. But at least it, along with other 1% of well-composed messages, are (so far, anyway) preserved for whoever wants to read them far in the future.

Elizabeth, also above, resolved to write her photos and videos to CD. This won’t work as CDs, like so many other types of storage media, will soon become obsolete. It reminded me of an former work colleague who had typed his PhD thesis on a computer in the early 1970s and stored it on punched tape (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punched_tape). By the early 90s it had long since become obsolete – so except for the hard copies in existence, the ‘information’ that was in the document was essentially lost. A surer way of preserving data is on a computer backup disk, with the data transferred to new computers as old ones are disposed of.

I heard recently that huge amounts of important research data (scientific, medical etc.) is being lost because, despite being neatly stored on the researcher’s computers, it gets lost when the person responsible moves on, passwords are lost etc. Perhaps “clouds” will change this, but I’m not so sure.

As for writing style, I expect style is irretrievably changed with emails.

Drew, I think you are very unusual in having saved all of your emails – in fact I can’t imagine how rare it is! Thanks for your feedback.

Allison … a wonderful piece. Any letters my father may have written home have been long lost, so I enjoyed this vicariously. On the soon-to-be-lost art of letter writing, I think cursive will disappear with it. I asked my son to add a couple of shopping items to the chalk board list in the pantry, and he came out chuckling. “I did my best to imitate your beautiful cursive. We didn’t learn to write like that in school.”

Touche, Cheryl. My kids admit to finding it difficult to write and my husband prints everything!

I loved this post, and I shared it on my own Facebook page called “Elinor Florence – Author.” As a journalist, blogger (Wartime Wednesdays) and soon-to-be-published author (my first historical novel called Bird’s Eye View is about a young Canadian woman who joins the RCAF in World War Two), I love and appreciate the value of old letters.

And I agree wholeheartedly that the world is losing a permanent record of the thoughts and feelings of an entire generation.

Thanks for your post, Allison Howard.

And thank you Elinor for your thoughtful words. I will look forward to hearing about your book!

I thought long and hard before I published a compilation of my grandfather’s war/love letters (Dear Harry; the Firsthand Account of a World War I Infantryman). The letters were personal and private, but I agree with your assertion that war letters are ‘an uncensored view into a world we might otherwise never have known.’

I am reminded each Remembrance Day that we can not remember what we have never learned. I look forward to more such letters surfacing.

Allison, I love your thoughts on the importance of hand written letters, especially as they relate to chronicling such major events as war. You are quite right about the ‘uncensored, spell-check free’ leaving an authentic account of the times. I am a huge advocate of the lost art of letter writing in our society in general. In fact I am a bit of a stationery junkie so I need to write letters to feed my habit… 🙂 You may enjoy a blog I write about such things. I will be sure to share this on social media. Lovely to meet you.