ONCE UPON A TIME in the Okanagan Valley, there was a young girl said to be the apple of her uncle’s eye.

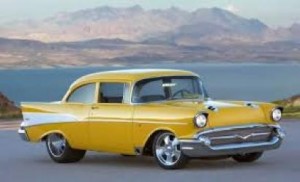

He would spirit her off in his car to teach her to drive, when she was just thirteen. It was so illicit and exciting, setting out on the highway at the wheel of the yellow Chevy, far from her aunt’s eagle eye. He taught her to gauge the closeness to the verge by the way the roadside lined up with the ornament on the car’s “bonnet” (he was from England). He taught her how to smoke cigarettes, and how to pinch the butts and hide them in her pocket, so the ashtray would not betray their escapades.

In the winter, when there were parties in the big ranch living room and the aunt was calling out the square-dance steps, the uncle would nudge the girl and say, “Shall we go and stoke the furnace?” They would slip away to the basement. He’d throw a log into the monster with the octopus pipes. Then he’d fish down a bottle stashed above one of those pipes and they’d both take a delicious illicit swig, and he’d wink, and they’d go back upstairs.

That was the extent of it.

Except for the feeling.

The lit-up feeling not so much of the whisky, as of being the apple of someone’s eye.

“FOR CAT’S SAKE where were you, Charles?” the aunt would say, if the uncle and the girl had spent long enough away to be missed: if he’d become dreamy from a second swig of whisky in the shadowy basement and got lost in telling the girl of growing up in England … of the great family house that had gone to his eldest brother because the property was “entailed” … how he was sent out to Canada to make his way … how he met the aunt and her sister (the girl’s mother) when they came riding across his newly ploughed field — invading his property as if they owned the world, “like goddesses” — one with golden hair, the other with a long black braid and a profile fierce and beautiful as Diana the Huntress and as fatal. For he could not look away.

“For heaven’s sake speed it up, Charles,” the aunt would say at meals when he was carving.

At that he would stop altogether and give the knife a few thoughtful sweeps across the sharpening steel before carrying on, slicing the beef paper thin (and reserving a crispy piece of “outside” for the girl).

“Speak louder, Charles,” the aunt would demand when he was telling a story at the table, and he would drop his voice so that even the girl could barely hear …

THE AUNT, YES THE AUNT. A terrifying figure when the girl was little, later a thrilling and compelling one who truly was a huntress: the ranch house displaying pelts of bobcat and lynx on the walls, a bearskin in front of the fire, a stony-eyed moose head above. She organized trail rides into the wilderness and horseback treasure hunts and paper chases and parties, and loved to surround herself with young people.

The girl did not want to be pierced by her gimlet eyes, though, when she’d been too long away from the dance. But the delight of complicity was greater, and of being the only one who listened to her uncle’s stories. Her. The apple of his eye. And the wonder, even then. How could he stand it? How had he allowed himself to be so eaten by the dogs of love? Surely he longed for escape.

MANY YEARS LATER and after many twists in the road, the woman who was once that girl was heading back to Italy. In her pocket was a Canada Council grant to aid in research for her Tuscan/Etruscan novel.

It had been breathtaking, some months before — as she climbed the slope above the old Tuscan mill house where she and her husband were staying — to have the idea for that novel touch down softly, like a butterfly, perfect, complete.

Back in Canada, though, after dissecting the specimen to produce a successful grant-application, she was troubled. It was encouraging, yes, that Etruscans had marched into the story, and a troupe of pursuing archaeologists, and that two love interests now distracted the central character, Clare — but something the writer had originally sensed was proving elusive. How to tune out all that bustle, and trace the shiver of unease at the novel’s heart, a tiny pulsing hidden even from itself, masked by the flash and dazzle of suspended flight? And once she found it, how to write it?

ONE NIGHT, just before she left for Italy on her research trip, the writer was at a party where she overheard an art school student telling of an inheritance she’d received from an uncle, on the condition that she transport his ashes back to his homeland (Germany) where she was to dispose of them “as she saw fit” — a request that had angered the student. Instead she’d stretched a canvas, taken out her acrylics, mixed the ashes in with glaring colours, done some expressionistic daubing, and shipped the result off to an art fair in Cologne.

An uncle’s ashes! (But why had the student been so angry?)

No matter. Words of her own began buzzing in the writer’s head.

Uncle. Ashes. Lawyer.

Niece summoned home. Scandal-making terms of uncle’s will.

Local papers a-buzz. Italian property left to niece. Nothing to wife.

Aunt stands guard at farm gate with shotgun, to warn off international press.

I GRABBED THOSE SNIPPETS. I carried them onto the plane in the company of my troubled character, Clare — just as she smuggled ashes aboard in a plastic makeup case.

It’s taken me a long time to shift into the first person here.

For the reclusive, the stealthy, and the abashed, the excellent thing about writing fiction is not only the possibility of sneaking into the heads of others, but the way personal experience can be buried, then dug up and resurrected, in a manner that might illuminate beyond the purely personal.

I’ve written elsewhere about the story of the ashes: how overhearing it lit the real spark for my most recent novel, The Whirling Girl. But until Allyson Latta generously invited me to join a discussion on how inspiration in both memoir and fiction may rise from personal experience, I have avoided tracing Clare’s deep and conflicted emotions back to the confused sense of power of that adolescent girl in the Okanagan Valley — who was, of course, me.

Indeed it took me many drafts of the novel before I could bring myself to let that fictional relationship turn a corner into the dark territory where it needed to go. I was held back (I realize now) by not wanting to sully memories of my beloved and only mildly mischievous uncle — a man of utmost correctitude, really, even though he did introduce a thirteen-year-old to cigarettes and whisky — or to consider what part that mischievous collusion might have played in the long and covert guerilla war he fought with his beautiful dominating wife.

But isn’t that a fiction writer’s job? To burrow as deeply into the personal as into imagined experience, to pull up hidden flecks of truth that can be stretched and melded into situations that are not entirely “made up” because at the core is that frisson, Yes, I am onto something real. Writing about “real people” is always tricky, in fiction as much as in memoir. Don’t both disciplines aim to take hold of truth and gel it into a heightened form that quivers with the same intensity a dream has? Though it must remain glistening with life all the same, and recognizable in an essential way.

And always there is the question: What right do I have? No wonder it can be hard to reach in and touch a story’s true, peeled-back, beating heart.

THEN WHERE DO THEY go, these everyday characters from past or present, transmuted for purposes of our own as writers? After we’ve used what we need, do they recede into their once-remembered selves? Or might they retain a sort of other-worldly radiance that can come flashing back to smite us?

The sisters invaded his land like goddesses — one with golden hair, the other with a profile fierce as Diana, and as fatal. For he could not look away.

Am I, too, fatally caught? Having brought them to light again?

♦ ♦ ♦

BARBARA LAMBERT’s novel The Whirling Girl was published in the fall of 2012. Her previous work includes A Message for Mr. Lazarus (2000) and The Allegra Series (1999). She has won the Danuta Gleed Award for Best First Collection of Short Fiction and The Malahat Review Novella Prize, and been a finalist for the Ethel Wilson Prize and the Journey Prize. Lambert is currently editor of the online literary Salon des Refusés, Dr. Johnson’s Corner. Discover more about The Whirling Girl and Barbara’s writing at: www.barbaralambert.com.

BARBARA LAMBERT’s novel The Whirling Girl was published in the fall of 2012. Her previous work includes A Message for Mr. Lazarus (2000) and The Allegra Series (1999). She has won the Danuta Gleed Award for Best First Collection of Short Fiction and The Malahat Review Novella Prize, and been a finalist for the Ethel Wilson Prize and the Journey Prize. Lambert is currently editor of the online literary Salon des Refusés, Dr. Johnson’s Corner. Discover more about The Whirling Girl and Barbara’s writing at: www.barbaralambert.com.

Barbara – These are rich memories you’ve mined, considered and shared. As I read I felt the thrill of being special at thirteen: driving, smoking, having a nip. … And the sentence, “The sisters invaded his land like goddesses — one with golden hair, the other with a profile fierce as Diana, and as fatal.”- glorious, vivid, active, evocative. Love it.

Hello Mary — What a heartwarming comment. I’m so glad my piece pulled up those 13-year-old memories for you. Also — now that I have discovered your interesting website, not only with its in-depth reviews, but with such an intriguing look at the forthcoming Washburn Island, which looks terrific — I look forward to following your work and your ongoing posts! Thank you!

Best wishes, Barbara.

Barbara, this story touched me deep inside.

As a child I was always begging Dad to let me steer the car and he acquiesced. I sat on his lap for many a mile on several trips from one end of Australia to another. Of course, in those days there was virtually no traffic. You’ve triggered a memory for me and I will pursue the topic of driving lessons. Very early on, Dad and I came to the conclusion that Mum would never learn to drive as all of his patient instruction resulted in her confusion over the gear change and her in tears. We three girls in the back stifling giggles and tears in sympathy with Mum.

I went for and passed my driving licence on my fifteenth birthday in Christchurch, New Zealand. This included a three-point turn on a very steep hill. Dad said, “Show them your double (de)clutch gear down to first move. That will impress your examiner.” And it did!

I’ve started another story too. This humid tropical heat is really wonderfully helpful in transporting me back to those childhood locations. I can hear the beetles and the bees and my father’s sonorous voice wafting out to us from the shady veranda.

Allyson, thank you for your constant inspiration, and your shepherding of an emerging writer.

Carol, thank you for your comments, and your fascinating re-creating of childhood moments! How lovely to hear your voice. Good luck with your new story. And I agree, Allyson is a constant inspiration to so many!

Barbara.