“Food memoirists understand that they are writing about everyone’s strongest basic instincts as they tell their own life stories. Food memoirs increasingly command our respect as we respond to their depictions of intense emotions, pleasurable recollections of communal and private food experiences, messages of familial wisdom, and insights into cultures.”

—Barbara Frey Waxman

AL: Barbara, you’re a professor of English and one of your courses at the University of North Carolina Wilmington is titled “The Food Memoir: Tales of Family and Culture.” How and when did you become interested in culinary memoirs?

AL: Barbara, you’re a professor of English and one of your courses at the University of North Carolina Wilmington is titled “The Food Memoir: Tales of Family and Culture.” How and when did you become interested in culinary memoirs?

BFW: I’m an avid reader of multicultural American memoirs and have also taught courses on memoirs of immigrants to the U.S. and Americans travelling abroad. My grandparents were immigrants from Eastern Europe and this may be one reason for my attraction to these texts; they have an emotional resonance for me and they also help readers to speculate on what it means to be and to become an American. These memoirs also examine the many layers of the American Dream and explore the American family’s values.

As a regular reader of The New York Times Sunday Book Review, I began to notice about five years ago that some of these multicultural memoirs had food as a central theme in the memoirist’s textual construction of identity. Also, more and more writing about food issues entered the public consciousness via the media; some of this consciousness has to do with the emergence of the slow food movement and the ecology movement too (how we cultivate food, producing and consuming food mindfully, treading lightly on Mother Earth). These issues are very appealing to me and to many other American readers; couple these factors with my joy in cooking, and my passion for reading and teaching food memoirs is explained. For students, I’ve consistently observed, food memoirs’ examinations of family life, including dysfunctional families, are also meaningful and moving.

AL: What do you believe chef James Beard meant when he spoke of “taste memories”?

BFW: I think he meant that taste memories are memories associated with specific meals or food experiences. Taste sensations would be central to these memories and especially when the food being tasted is for the first time (a “virginal” food experience!). These memories might also be linked to the people with whom he dined and their interactions around the dinner table.

AL: The premise of your article “Food Memoirs: What They Are, Why They Are Popular, and Why They Belong in the Literature Classroom” (College English) is that good culinary memoirs are literature worth studying. Would you share your thoughts on this?

BFW: Like other good literature, good culinary memoirs are well-structured, create an interesting—often witty—narrative voice, evoke vivid scenes containing lifelike dialogue, have a page-turning plot that thickens and a turning-point or two in the author’s life, and develop complex characterizations, not only of the author but also of what Eakin calls “proximate others” (parents, siblings, spouses, close friends and mentors to the author). Good culinary memoirs offer great descriptions of food preparation (process analysis) and sensory descriptions of food consumption. They also use food imagery on a deeper metaphorical and symbolic level that invites readers of all backgrounds and experiences to use their interpretive skills, to dig deeper in their ways of reading, to recognize subtexts in the narrative. Literature teachers love to explore these things in their classes. In addition to these aesthetic elements, food memoirs often have a philosophical or a psychological bent, with the memoirist reflecting upon what makes life meaningful, how to create a happy life, how to construct one’s own identity: issues well worth studying. Finally, they teach us about different cultures, their values, their politics, their practices, invaluable lessons that promote global understanding.

Good culinary memoirs are literature worth studying, as well as an avenue to lessons in anthropology, politics, history, psychology, and sociology. Since food matters to almost all of us, learning takes place in a lively and engaging context through these entertaining texts.

AL: You distinguish between two sorts of culinary memoir, the “most fully conceived” being those that chronicle the memoirist’s development from childhood. Can you explain the distinction between these and other food memoirs?

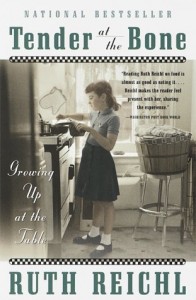

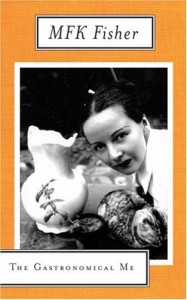

BFW: When I select culinary memoirs for my class, I try to find those that go back to the earliest food memories and memories of family life, and that trace the development and coming-of-age of the memoirist. I’m a bit less interested in works that just depict the author’s adult life experiences as a professional chef or as a food/restaurant critic. So for example, I prefer teaching (and reading) Ruth Reichl’s Tender at the Bone to her more recent Comfort Me with Apples or Garlic and Sapphires because the former goes back to the origins of her food memories and food passions, goes back to her early girlhood. M.F.K. Fisher’s The Gastronomical Me also goes way back to early memories in the kitchen so I like to include her in my course.

BFW: When I select culinary memoirs for my class, I try to find those that go back to the earliest food memories and memories of family life, and that trace the development and coming-of-age of the memoirist. I’m a bit less interested in works that just depict the author’s adult life experiences as a professional chef or as a food/restaurant critic. So for example, I prefer teaching (and reading) Ruth Reichl’s Tender at the Bone to her more recent Comfort Me with Apples or Garlic and Sapphires because the former goes back to the origins of her food memories and food passions, goes back to her early girlhood. M.F.K. Fisher’s The Gastronomical Me also goes way back to early memories in the kitchen so I like to include her in my course.

In contrast, Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential stays mainly in his adult life and less on the trajectory of his development into an adult so I don’t teach his book. The beautiful book by Barbara Kingsolver (and family members), Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, which I really enjoyed, would not fit as well into my course since it only examines a year in the life of the family, and is not aiming to trace the trajectory of a person’s life story. It still should have a revered place in the larger world of food writing!

AL: What literary elements do you feel the most powerful culinary memoirs share?

For me the most powerful food memoirs offer an intimate portrait of family life and vivid sketches of important people that shaped the memoirist’s identity, descriptions of a culture’s values and practices, a representation of the ways of celebrating holidays and other special days through food (with their preparation and consumption well described), a discussion of the memoirist’s cultural beliefs as they evolve, and finally, a sharing of the culture’s folk tales and of family tales told around a dinner table or around a stew pot in the desert. Readers should have a good understanding of the memoirist as person by the end of the reading—or of the person that the author wants us to see. A sense of humour also seasons the most powerful memoirs that I have loved. Finally, the most powerful memoirs also offer a snapshot of an historical era; I think of Madhur Jaffrey’s depiction of Partition and the birth of India and Pakistan in 1947 and what this historic moment meant to her and her family. I think of how wittily Ruth Reichl is able to capture and gently satirize the communes and hippie scene in California in the 1960s and 1970s.

AL: You refer to M.F.K. Fisher, author of The Gastronomical Me (1943), as the “founding mother of the American food memoir.” What was groundbreaking about her book?

AL: You refer to M.F.K. Fisher, author of The Gastronomical Me (1943), as the “founding mother of the American food memoir.” What was groundbreaking about her book?

BFW: Fisher herself indicates the unique focus of her book in her preface, which defends her reasons for writing a book about food, and also expresses her pride in doing so. She defends her topic as profound and says that when she writes about food she is really writing about human hungers and about love and the need for love. She then does that, probing the powerful human passions in her own life (though at more of a distance from readers than more contemporary memoirists). She also explores the symbolic potential of food; for example, in a scene she recalls herself as a young woman in late adolescence tasting oysters for the first time and she obliquely addresses her unfolding sexuality and erotic desires, including her desire for women as well as for men. She writes of her passion for Chexbres and of her divorce from her husband Al. Very bold of her.

I also think she is unique as a pioneer in discussing politics in her food memoir, politics about well-prepared, fresh, local French food; gender politics (she writes about crossing the Atlantic by ship as a woman alone and about dining as a woman alone; she also denounces in one scene the emotional victimization and manipulation of a young woman by her boyfriend in the boarding-house in France where she and her husband are living). She is an early pioneer in writing about politics (such as about the rise of Nazism in Europe and her own distaste for German Nazis on board her ship during her many crossings); such topics were really not considered compatible with discussions of food—until Julia Child in the next generation of food memoirists discussed with vehemence the political tactics of Joe McCarthy and “his henchmen,” even as she waxed eloquent upon French bread and sole in butter sauce.

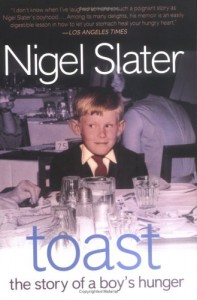

AL: Toast, by Nigel Slater, is a personal favourite of mine, and I gather of yours too. For you, what is it about Toast that sets it above some of the rest?

BFW: Nigel Slater’s sense of humour sets his work above some of the other food memoirs (although Ruth Reichl is very witty too). Slater does not seem to take himself too seriously. He is also brave about revealing his vulnerability and the painful scars and losses of his boyhood. His depiction of his father is very effective: the vivid portrayal of his father’s cruelty through food (a kind of force-feeding to turn him into a manly man). Slater is a gutsy nonconformist. Finally, his descriptions of foods are precise and vivid without piling on too many details (I recall his steak Diane vs. steak tartar). I also think his structure, the short, pithy sections of his narrative and their punch-line endings, are appealing to readers.

BFW: Nigel Slater’s sense of humour sets his work above some of the other food memoirs (although Ruth Reichl is very witty too). Slater does not seem to take himself too seriously. He is also brave about revealing his vulnerability and the painful scars and losses of his boyhood. His depiction of his father is very effective: the vivid portrayal of his father’s cruelty through food (a kind of force-feeding to turn him into a manly man). Slater is a gutsy nonconformist. Finally, his descriptions of foods are precise and vivid without piling on too many details (I recall his steak Diane vs. steak tartar). I also think his structure, the short, pithy sections of his narrative and their punch-line endings, are appealing to readers.

Click here for Part 2 of my interview with Barbara.

BARBARA FREY WAXMAN earned her PhD in English at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. She is Professor of English at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, where she has taught literature since 1982. (See Part 2 for detailed bio.)

Dr Waxman shows a wonderful command of this literature.

Yes, she does. She gives a great overview of the genre and makes some fascinating observations on the appeal and value of the best food memoirs.

Dr. Waxman’s responses reflect how food traditions represent a major approach to understanding and appreciating who we are. A great genre and a great interview!

Don Hickman

Thanks, Don. Speaking to Barbara has certainly enhanced my appreciation for food memoirs.

Barbara’s description of these three memoirs compels me to read them. I’m hungry for them! Thanks for the tasty interview!

Dr. Waxman is a joy to read and listen to. What a great topic.